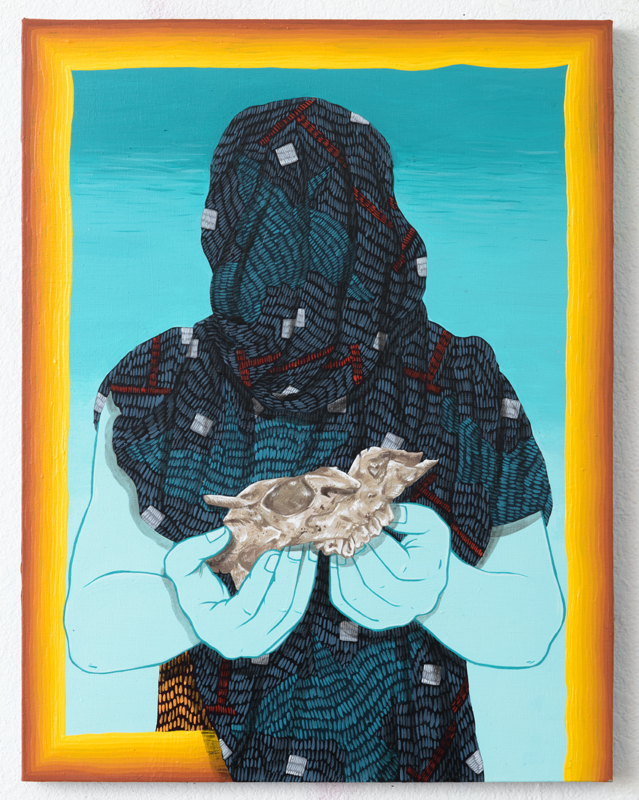

Amir H. Fallah. The Costume Maker, 2016. Acrylic and collage on paper mounted to canvas,

3’ x 4’. Courtesy of the artist.

Art galleries have a complex relationship with neighborhood identities. The appearance of a “white cube” space is a status symbol, but it also signals a process of transformation and displacement. More recently, the art world has been repurposing abandoned spaces, sometimes in up-and-coming neighborhoods, when they have outlived their original function but are yet to be destroyed. Human Condition, which opened this weekend in the out of-use Los Angeles Metropolitan Medical Center in West Adams, is no different. Curated by John Wolf, this sprawling exhibition of over eighty artists (many with their own whole-room installations) sits just south of the 10 freeway. The artists exhibited range from recent art school graduates to luminaries like Jenny Holzer and Robert Mapplethorpe. The press release touts the nascent “cultural renewal” in the neighborhood: “Years of neglect are now giving way to reinvestment in West Adams, which hosts much of the city’s cherished architectural heritage and landmarks,” it reads, citing the “many working artists,” that recently moved there, as well as the “burgeoning art scene.”

The hospital is the ultimate setting for a show that evokes an identity in limbo. It shut down three years ago in the wake of decay and fraud accusations. A sense of institutional erasure and neglect hangs heavy over the location, which has still not been scrubbed of all its disturbing smells and stains. A sink is stained with chunks of an iodine-colored substance; a lingering odor of formaldehyde permeates the second floor.

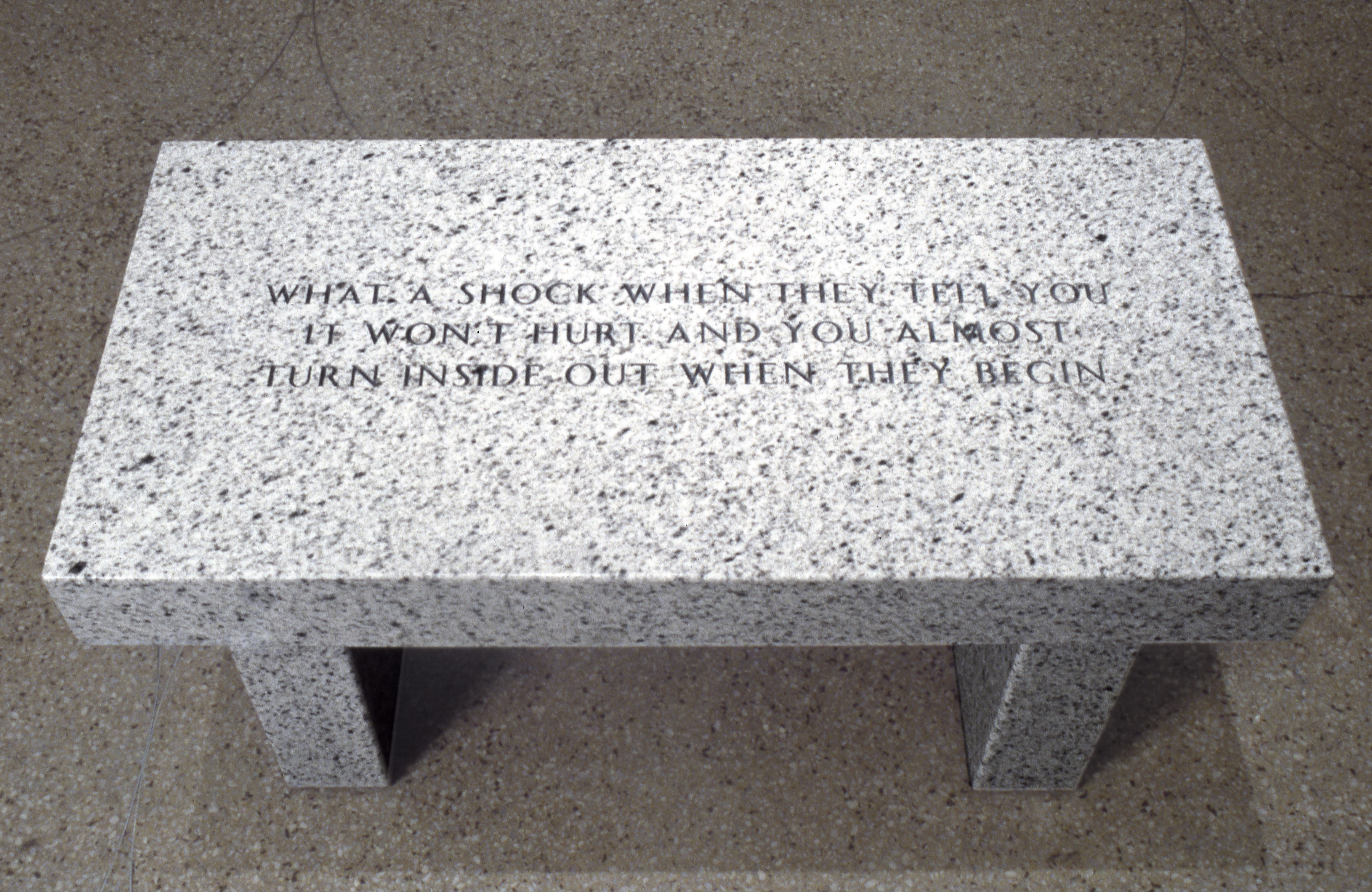

Jenny Holzer. What a shock when they tell you it won’t hurt…, 1989 . Bethel white granite bench . Text: Living (1980-82) 17 x 36 x 18 inches . Edition AP (from an edition of 3 + 1 AP). Courtesy of the artist and Sprueth Magers.

As you enter the abandoned space, the stringent smells and hospital décor give you a whiff of the same sense of self-abandonment you may feel when entering a functioning hospital room, are given hospital clothes and perhaps sedatives. The three-dimensional works add to the sense that you are wandering through the manifestation of someone’s mental limbo state—the mixture of anxiety and deliriousness that precedes the moment before you go under for a procedure.

On the first floor, Christopher Reynolds painted the hospital kitchen and cookware entirely in “prison pink,” a color that is scientifically proven to reduce both aggression and appetite. Exposure to this color reduces the desire to express your anger, and your desire to eat, rendering you sedate and less emotionally human.

This room, which you’re likely to encounter early in the show, is the foundation for a feeling of collective nausea and anonymity that will continue to build as you encounter a number of figures with obscured or even monstrous faces. One room contains Daniel Arsham’s sculpture of a figure totally obscured with a viscous white drapery, save for one boot-shod leg. The work brings to mind a lost patient wandering, clouded in his own thoughts, or even a ghost.

Daniel Arsham. Standing Figure with Drip, 2011, Fiberglass, paint, joint compound, mannequin, fabric, and shoe , 67 x 36 x 36 in. Courtesy of Moran Bondaroff.

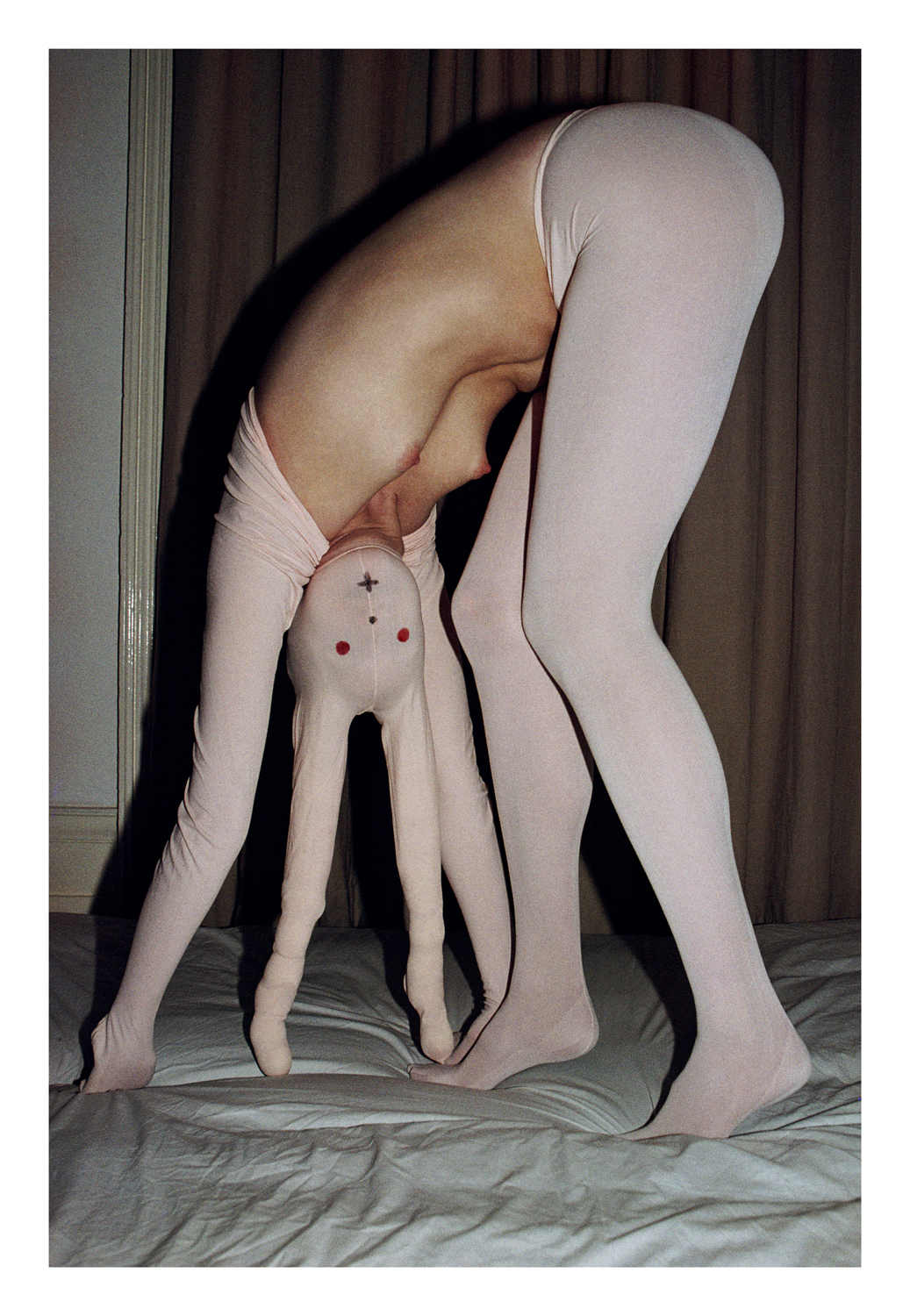

Amir H. Fallah’s room offers some sense of refuge from the unsettling atmosphere that permeates the hospital, but it is also integrated into the continuous experience of this show. The room is arranged in a way that is reminiscent of a shrine, so you feel that you could be in the hospital chapel, or perhaps you’ve moved on from the hospital scenario to the next step—visiting the dead. The installation looks like a shrine, but instead of candles, there are cactuses, warmed by purple heat lamps. Instead of photographs commemorating the faces of the dead, there are paintings from Fallah’s collected portraits, which identify people by their possessions rather than their faces. The subjects are obscured; they clutch memorabilia as tapestries and tablecloths cover their faces and bodies. This use of objects as a placeholder for human identity adds to the funeral feeling of the space.

While the sculptural pieces are integrated into the hospital’s ethos, the two-dimensional works take you out of it, reminding you that you are not in a dystopian hospital nightmare, but at an art show. This perceptual shifting adds another layer of confusion about the identity of the space. In his installation of works on paper, untitled (175 heads), Brendan Getz filled a small room floor-to-ceiling with a series of abstract faces, each with varying degrees of recognizable features. Some have eyes and noses while others have none, and perhaps are only recognizable as faces because they are positioned among other faces. Polly Borland’s works eerily bridge the dimensional gap: in one room blobby leg sculptures made of stuffed nylon fall out of open lockers—toward photographs that obscure their human subjects with nylon masks.

Amir H. Fallah. Between Two Hands, 2016. Acrylic and colored pencil on paper mounted to canvas, 32” x 36″. Courtesy of the artist.

Other obscured faces abound on the hospital walls. Each is a window into an individual buried psyche: the images are collective in their expression of an in-between state, individual in the mode of that expression. Ross Chisholm’s painting Marqise cha cha features a barely formed face, which appears to be illuminated from behind. A curved brush stroke almost resembles a smile. The figure is neither solid nor ethereal.—it could be the vapor of your own consciousness as you imagine yourself somewhere else.

Human Condition is an absorbing example of collective, experiential art. While white cube spaces can provide the context that transforms everyday objects into ready-made artworks, contextualizing constructed pieces among the residues of institution and disease has a kind of inverse effect. Unlike the blankness of a gallery, the tarnished space converses with, occasionally overshadows, and never glorifies the work. This shared context gives the show a sense of thematic collectivity that might have been less obvious in a more anonymous space; wandering through the exhibit, one has a continuous sense of a “crossing-over” between the human and the other-worldly, individual identity and obscurity, life and art.

Human Condition is on view October 1 through November 30, 2016 at the former Los Angeles Metropolitan Medical Center.