Now, being an artist also means creating a platform to monumentalize the wide range of cultural histories.

I grew up hearing the music of La Gran Manzana (The Big Apple) blaring from bodegas, six-floor walk-ups, and taxicabs. Henry Hierro, my father, is the singer/songwriter for the group, a fixture in the merengue movement popular in New York City in the 1980s. Raised in Manhattan at Dyckman and Riverside, aka Little Dominican Republic, I grew up in a basement apartment with an attached music studio. Music and creativity was all around me; being home was so much fun that I never wanted to leave for school. Around the dinner table, we spoke openly about life, and our voices were always heard. I knew I was destined for a life in the arts, but visual arts was something my family knew little about.

Art class gave me one of the few opportunities to be with the rest of the kids.

My father was a disciplined musician. Everyday, he’d wake up, get my siblings and me ready for the day, and then retreat into his studio. My mother was a musician in her own right; she often collaborated with my father by providing vocals on his songs. She worked as a nanny for families in the gated communities of Upper Manhattan. I still admire the patience and generosity she showed in all that came with that job. Above all, she was an amazing seamstress. Sewing skills were passed on from her mother and later inherited by me; I often use them in my work. My brother Chris was a graphic artist, and his comics were my first introduction to the visual arts. He ultimately followed after my father and pursued music. It’s as if he dropped the pencil, and I picked it up.

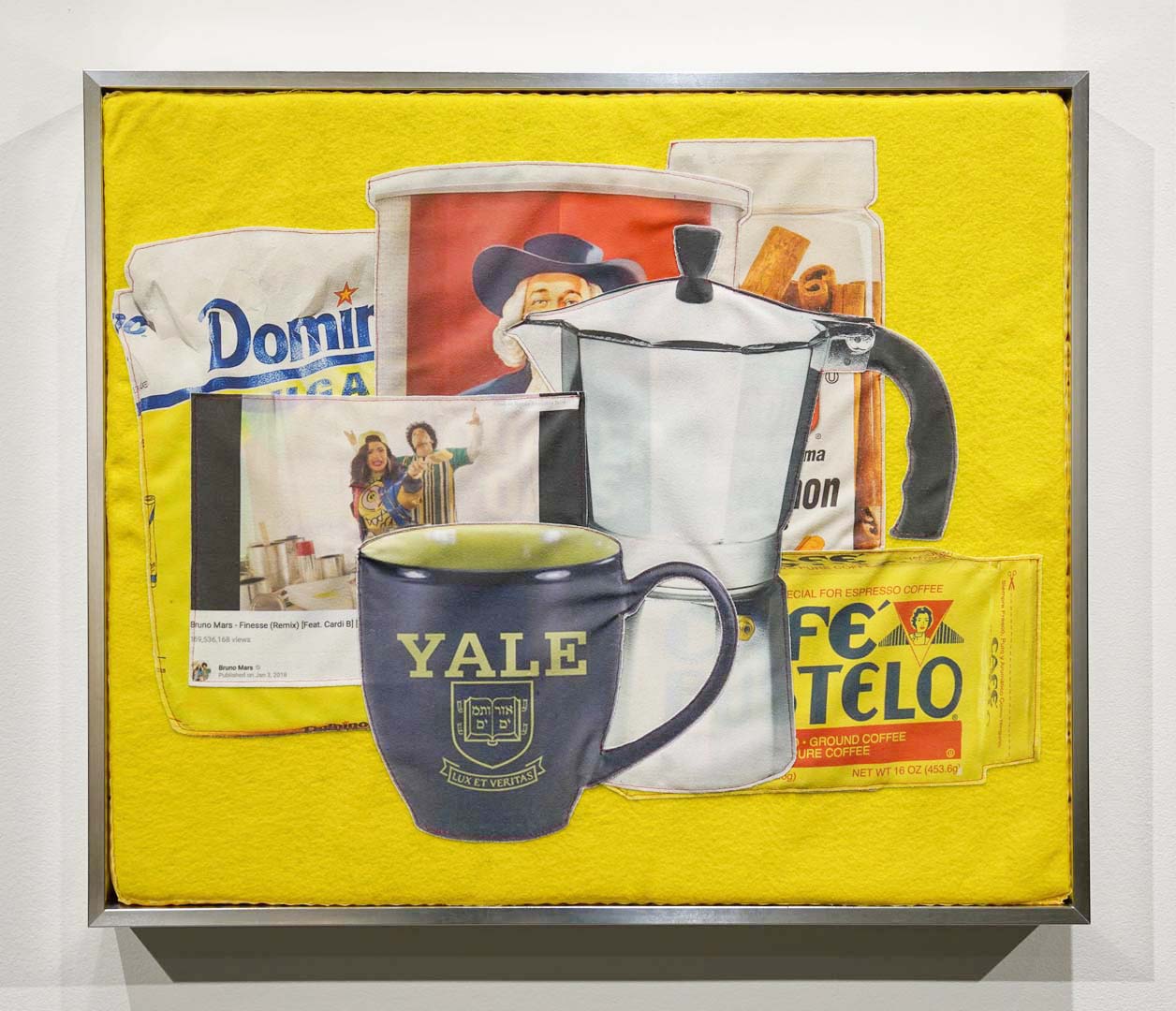

Lucia Hierro. Breakfast Still-Life With Greca (2018), 22” X 25.75” with frame; digital print on brushed nylon, felt. & foam. Photo by Matt Eaton. Image provided by the artist.

My interest in visual arts was sparked in elementary school, thanks to P.S./I.S. 187 Hudson Cliffs. Although I was born in the United States, my parents mostly spoke Spanish, and I was placed in English as a Second Language (ESL) classes. Moving between two classrooms everyday was daunting, but art class gave me one of the few opportunities to be with the rest of the kids.

The closest thing to Caribbean art history was found in Dutch still-life paintings

In 2000, my family and I moved to San Francisco de Macorís, Dominican Republic, my parents’ hometown. Access to the arts was limited, and adjusting to such a big move was mentally exhausting, so my curiosity for art took a back burner. When my mother and I returned to the States a few years later, I participated in a college preparatory program at Cooper Union led by Marina Gutierrez. Part of that program was a visit to Miguel Luciano’s studio, which had a huge effect on me. Until that point, visiting museums caused me much anxiety, but Luciano’s work illuminated what was lacking in those spaces: a narrative and experience that is relevant to me. His series Louisiana Porto Ricans, for example, reinterprets labels of agricultural exports from the 1930s, imagery that largely shaped representations of Puerto Rico in the United States. It made me realize that museums were not as informed and monumental as I had assumed. Luciano was also the first working visual artist I met. From my father’s work, I understood how a musician can work in a studio and generate an income, but I never knew an example of a visual artist doing that. After I met Luciano, art now existed in spaces I wasn’t aware of and spaces I saw myself in.

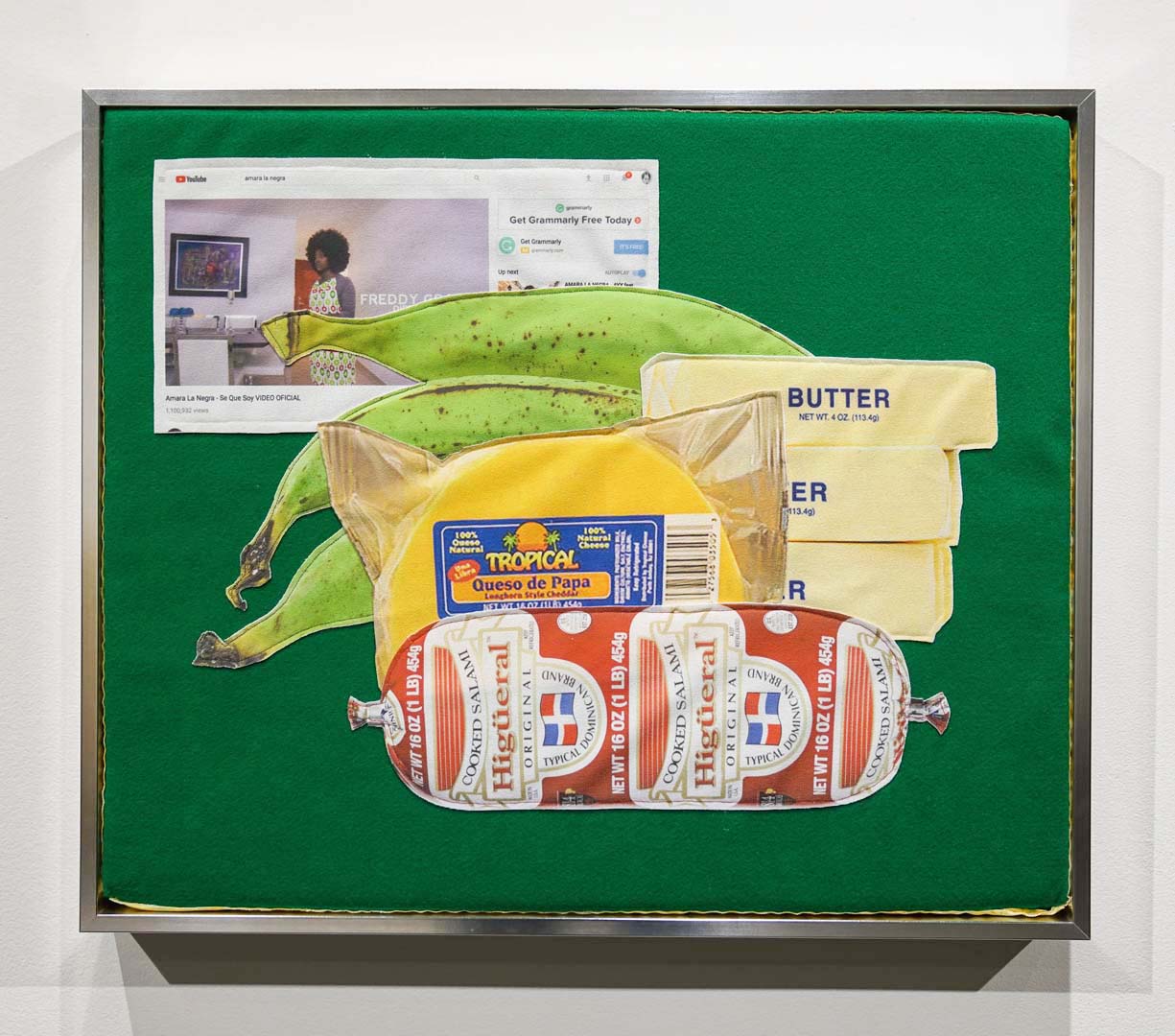

Lucia Hierro. Mangucito (2018), 22” X 25.75” with frame. Digital print on brushed nylon, felt & foam. Photo by Matt Eaton. Image provided by the artist.

Academia was missing the intersectional conversations in art that I was searching for, forcing me to search outside of the curriculum. At Purchase College, State University of New York (SUNY), I often joked that the closest thing to Caribbean art history was found in Dutch still-life paintings, featuring the goods acquired from their conquests. In contrast, I viewed these items and the role they played in my life as rich in culture. The book History of Modern Art by David Joselit featured few artists of color and focused on the usual canon of White male artists. The one-sided perspective forced me to conduct my own research; I am only recently learning about Dominican art history. With recommendations from my mentors, I found the writings of Coco Fusco and bell hooks, which had considerable influence on my creative process.

Lucia Hierro. Quien? Soy Yo! (2017), 24” x 36” x 2.” AMNY (2016), 24” x 36” x 2.” Digital print on fabric, stretched on foam. Both images by Photo by Matt Rodriguez. Image provided by the artist.

During my time at Purchase, I began to feel the effects of social and economic dynamics, which adversely affected my art practice. Lower-income peers dropped out, because they couldn’t afford the tuition. The lack of diverse cultural representations in the curriculum meant I had to defend my work and cultural references; one critique questioned the significance of Spanish titles for my works. For me, the key to maintaining momentum was to be around what I loved.

I assisted the artist Dannielle Tegeder, who had a studio at Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts. She provided honest insight into the industry and business of being a working creative person, from building a sustainable studio practice, to applying for grants and residencies, to forming relationships with dealers and galleries. She taught me that some selfishness is required to really leave a mark in the art world. During that summer, a friend’s mother offered me her studio space in their house in Chappaqua. With the works that I made there, and the assistance of Danielle and another mentor, George Parrino, I applied to the Yale School of Art. I wanted to push my work, but I also understood the cultural capital and gravitas of being a Dominican woman with an MFA in painting from Yale.

As one of the country’s top studio-art programs, Yale broadened my understanding of the diaspora, its place in art history, and my place in that history. When I was introduced to the book The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Was, by Junot Díaz, I froze. The text effectively conveyed the experience of being a Dominican American in New York in a way that my art could not. I lost all incentive to paint and was almost ejected from the program. Additional stress was added by the prejudice on campus. My visibly Black peers were routinely asked for their IDs on campus. We reacted by advocating for the visiting-artist roster to include artists of color, like Mark Bradford and Juan Sanchez. Finally, professors like Erica James and Robert Farris Thompson supported our requests. These efforts and the support of my peers saved my studio practice.

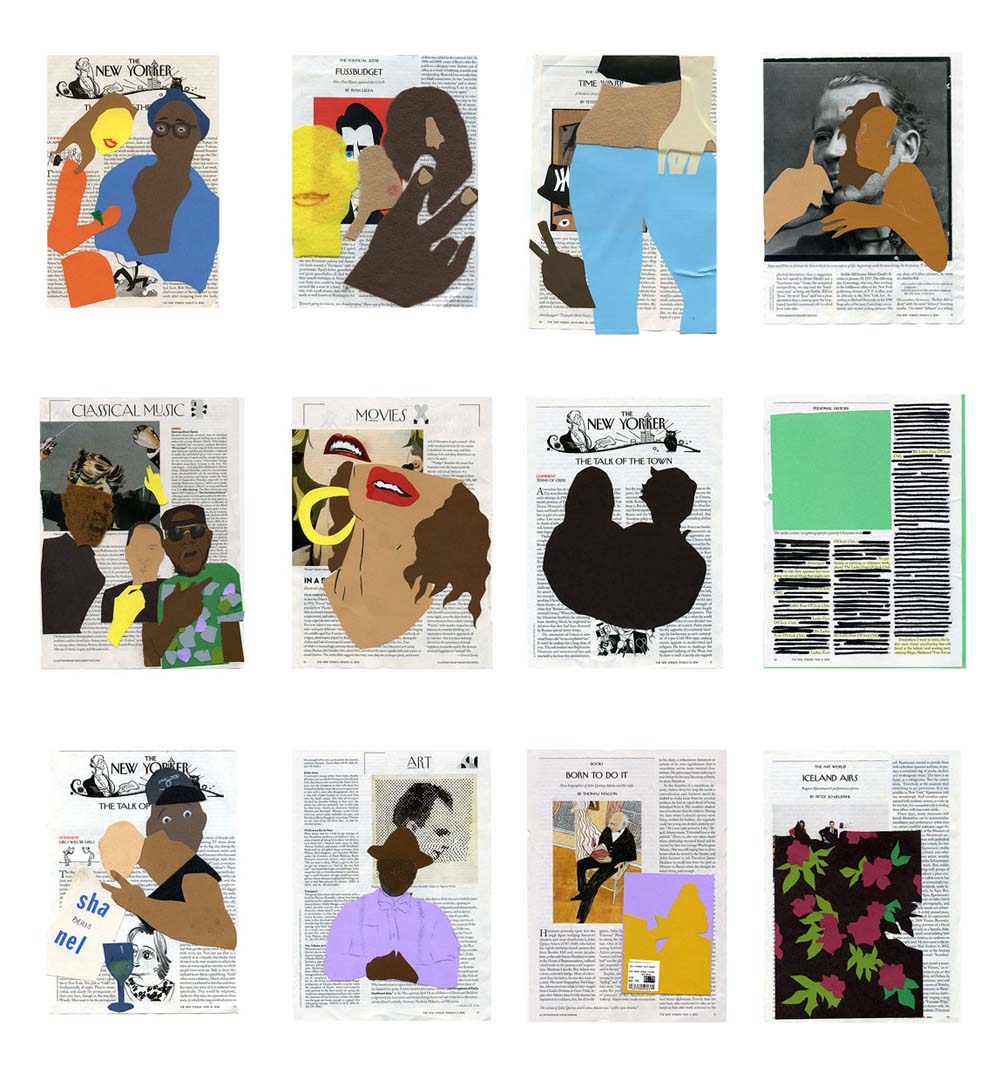

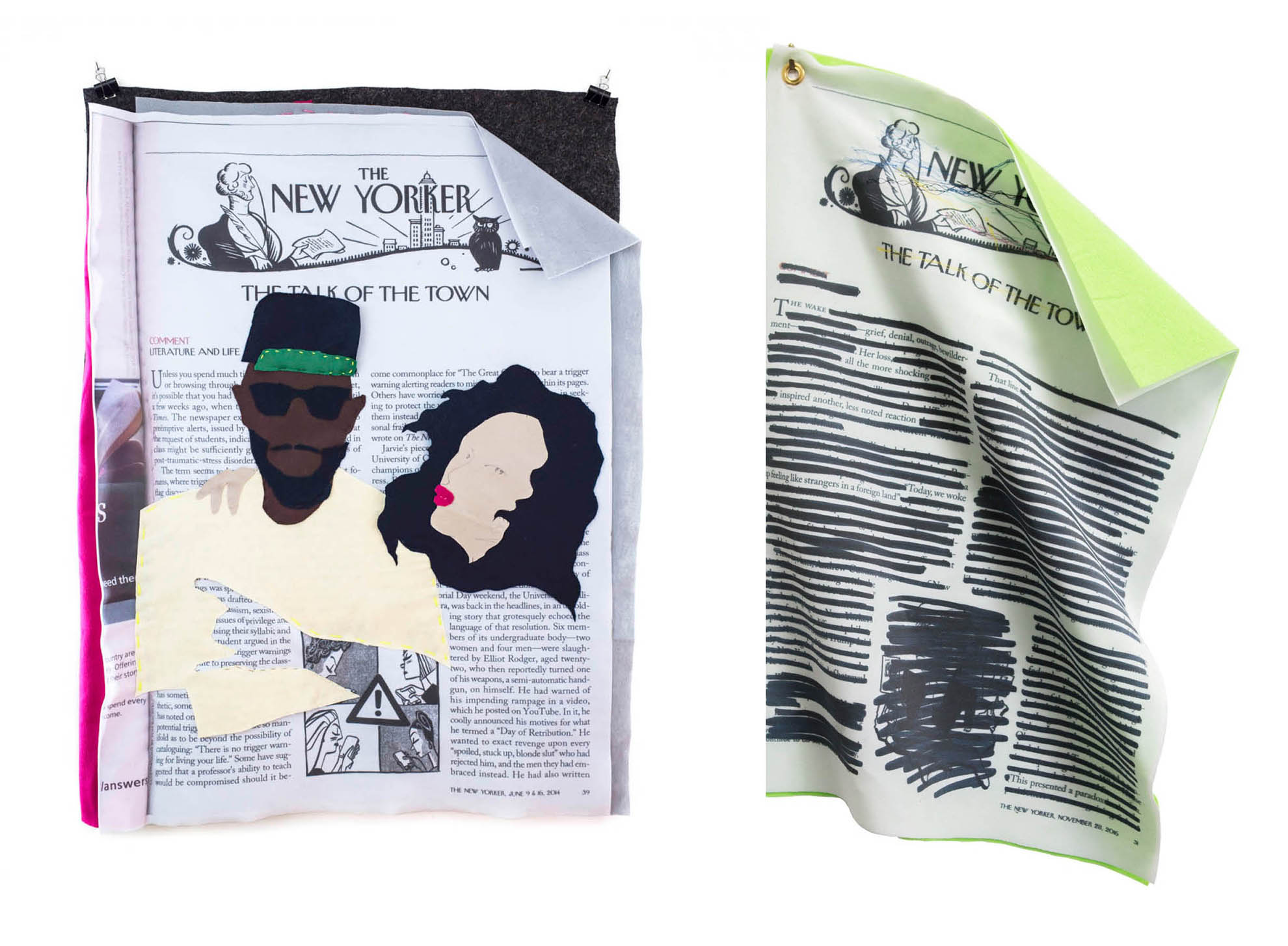

Lucia Hierro. Me and Bae, 2014. That Line Tho, 2016/17. From the New Yorker series. Digital print on brush nylon felt. Images provided by the artist.

During the middle of my time at Yale, I began working with fabric, which triggered memories of elementary-school art class. Art gave me the tools to communicate beyond language barriers. My New Yorker collage series was my first attempt at digitally printing on fabric. I used images from magazines as a catalyst for conversations about privilege, economic disparities, and lived experiences. Some found the series brilliant, and others were bothered by it; one of the comments in my final critique was that I needed to change my world view. It was difficult. I felt that I had something to prove in two spaces: at school and at home. While my Yale peers and professors didn’t understand my cultural references, my family worried about how I was going to make a living from being an artist, which was ironic, considering that we survived off of my father’s art (and my mother’s labor). At some point, I realized I had to let go of my expectations and just make my work with full force, whether the Ivy League or my family understood my mission or not. I wanted the work to be read on multiple levels, to appeal to the supposed art experts as well as to people with a similar upbringing to mine.

After graduating from Yale with an MFA, I applied to the Yaddo residency in 2013. One of the most prestigious artist residencies in the country, one that has hosted the likes of James Baldwin, Sylvia Plath, Jacob Lawrence, and Philip Guston, Yaddo gave me the tools to unpack my years in academia, in which I felt I was pushed and pulled in a million directions. Being with mid-career writers, playwrights, and painters made me feel like a true artist. If I had any doubts about who I was and what I was meant to be doing, I found validation at Yaddo.

At the start of 2018, I had my first solo show at the Elizabeth Dee Gallery located in Harlem. Titled Mercado, the series featured large bodega bags made of see-through polyester organza fabric and filled with images of objects, found online and digitally printed on fabric. These were encased in hard-cell foam and sewn shut to resemble objects that were simultaneously two- and three-dimensional.

Lucia Hierro. De Todo Un Poco, 2017 . PolyOrganza, felt, digital print on brushed nylon 60″ x 67″ (28” Strap). Photo by Etienne Frossard. Courtesy of Elizabeth Dee Gallery.

My mother helped me to sew the bodega bags in the series, and spending time together in the studio helped her to better understand my practice. Up until this point, my family didn’t understand my reasons for becoming an artist. When people would ask my mom what I did, she would respond with the few talking points that I’d provided, but I knew she and my family didn’t fully understand. They were unaware of the significance of some of my accomplishments, like being in a group show with Kerry James Marshall and showing at Elizabeth Dee Gallery. This studio time with my mother helped put my goals and my practice into perspective; she saw herself and her community reflected in the work, and her approval overshadowed that of any art critic.

Lucia Hierro. Habichuela con Dulce (Sweet-Beans), 2017. PolyOrganza, felt, digital print on brushed nylon. 48″ x 60″ (19” Strap). Photo by Matt Rodriguez.

The greatest acclaim of Mercado came from my family and community. The piece titled Sweet-Beans, now in the Rennie Collection in Vancouver, was my brother Henry’s favorite; it featured a large bodega bag filled with ingredients of his favorite Dominican sweet, one usually reserved for the holidays. My work may present new information to some viewers, but it is validating for those who know, and it can still be regarded as fine art.

Caribbean culture is such a large part of New York City but is still under-represented. While it’s validating to see corporate brands use Dominican aesthetics, like Nike’s recent De Lo Mio campaign, I remain critical of their intent. Now, being an artist also means creating a platform to monumentalize the wide range of cultural histories. Navigating between two worlds has always been a theme in my life and is the source of inspiration for my work. For the past four years, I’ve channeled my father’s discipline, and I work in my studio in the South Bronx. I am proud to call myself an artist.