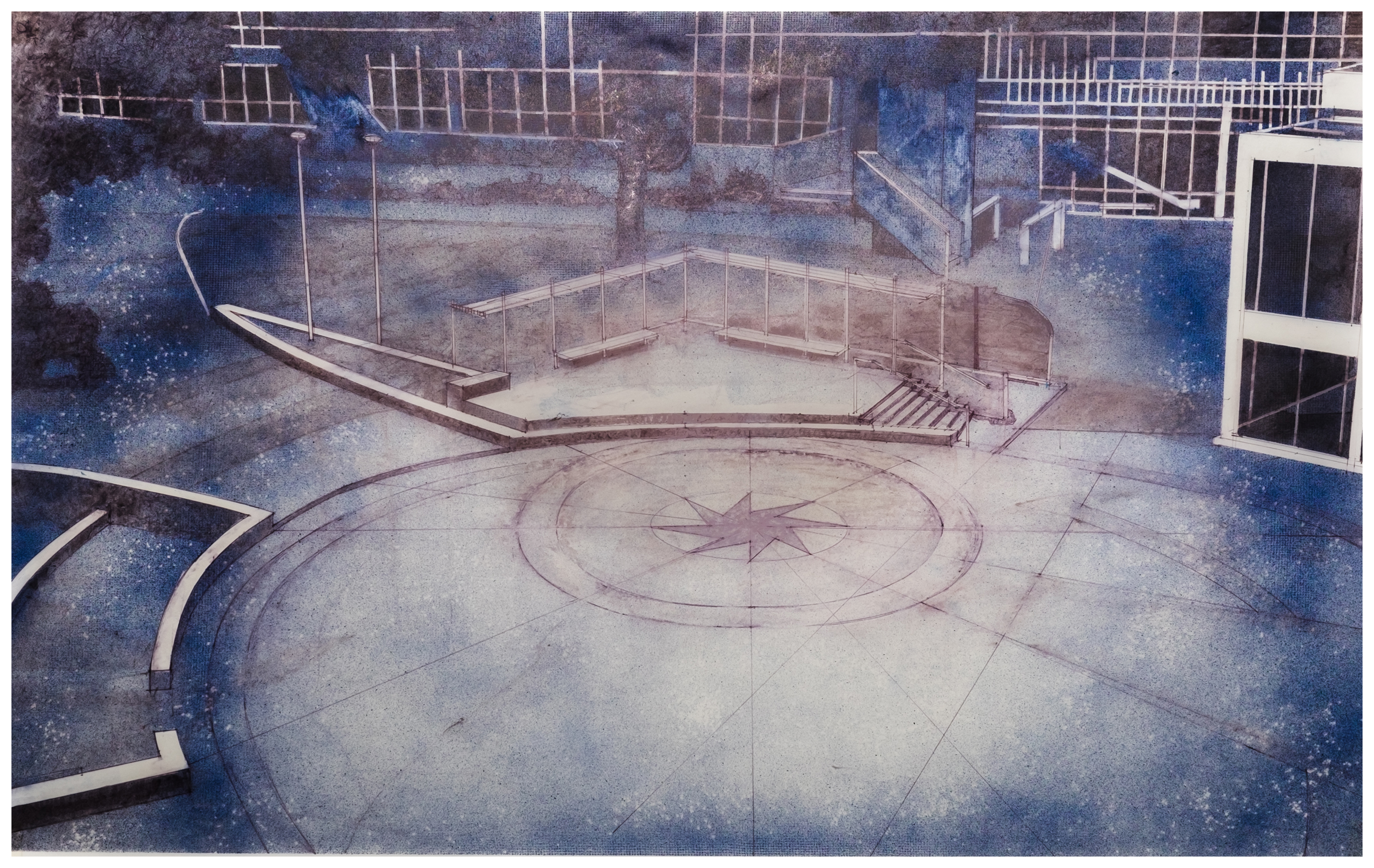

Jerome Reyes. the horizon toward which we move always recedes before us (San Francisco State Quad), 2018. Drafting ink, corrective fluid, sprayed house paint, painter’s tape on vellum; 21.5 x 34 inches. Image courtesy of the artist.

A conversation between PJ Gubatina Policarpio and Jerome Reyes.

This 2019 conversation took place in Jerome Reyes’s San Francisco studio and garden. Reyes lives between Seoul, South Korea, and his native San Francisco, and Policarpio recently moved back to San Francisco, with ongoing engagements on the East Coast. Policarpio is the curator of Solidarity Struggle Victory, and Reyes is one of the artists in the exhibition. Reyes’s studio holds key San Francisco State College (SFSC, now San Francisco State University) 1960s archives of student-designed curricula, which are central to the exhibition’s premise. In this conversation, both Policarpio and Reyes meditate on the larger implications of the show’s thesis in relation to time, pedagogy, movements, and camaraderie. This is the second installment of a two-part interview.

—PJ Gubatina Policarpio

Read “Reading at the Edge of the World: The Horizon Toward Which We Move (Part I).”

PJ GUBATINA POLICARPIO: I want to talk about your public art billboard, Abeyance (Draves y Robles y Vargas), currently at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts. Abeyance honors three Americans: the Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and filmmaker, Jose Antonio Vargas (born 1981); the poet and activist, Al Robles (1930–2009); and the Olympic gold-medal diver, Victoria Manalo Draves (1924–2010). It weaves together their words of migration, despair, and resilience.

I remember texting you a picture of the billboard as the backdrop to a visual cacophony of park visitors, downtown professionals, and nearby construction sites. To me, it’s this palimpsest of San Francisco, in particular of the South of Market (SOMA) neighborhood’s history and trajectory. This billboard above contains the concerns and dreams of the people.

Robles also appears in earlier projects, including Pharos (still a nice neighborhood) from 2016, shown [earlier] this year in the KADIST exhibition, Here We Live. What is the significance of these figures, sites, and memories?

JEROME REYES: The billboard image is actually of Ocean Beach in San Francisco. It’s literally the edge of San Francisco but also the United States, and for some people, it’s the edge of the world. What does it mean to have that edge, shifting by the second, with these words that speak to the irreducibility of the complicated politics this country has been facing, has inherited, and that are now made more transparent?

The billboard is located in the SOMA neighborhood, a site that during the 1980s and 1990s underwent dramatic redevelopment and displacement, which is still in process today. It’s also physically next to Revelation, the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial and waterfall, made in 1993 during the development of what is now dubbed the Yerba Buena Gardens. To make this work, I studied the heavily contested Yerba Buena development and an unrealized 1992 public art project intended for the nearby Moscone Center by the Los Angeles artist, Daniel Joseph Martinez, titled This is A Nice Neighborhood. Martinez’s lifelong practice of presenting provocative and incisive language, and his use of billboards and banners, serve as a direct art-historical lineage. So, at this already potent site, there is currently an international convention center, an art center, and gardens with global visitors mixed with locals, immigrant families, kids, seniors—a locale that could be a snapshot of the country.

Jerome Reyes. Abeyance (Draves y Robles y Vargas), 2017. On view at the Yerba Buena Center for Arts through Spring, 2020). Vinyl billboard; 30 x 30 feet. Photo: Jeremy Villaluz.

POLICARPIO: That reminds me: Vargas’s billboard text comes from the moment of separation from his mother at the airport. It’s interesting to think how far we have come in terms of not just violence against migrants but also what we accept in public; I’m speaking about the kids at the border, the graphic images. The billboard—choosing to make this moment visible in public space—is prescient.

You also recently joined the advisory board of the nonprofit media organization, Define American, founded by Vargas. In fact, you just attended the opening of Jose Antonio Vargas Elementary, his namesake school in Mountain View, California.

REYES: I met Vargas in 2011, when his New York Times feature revealed him to be undocumented, so we stayed in conversation discussing work and research. I reflected on how someone who immigrated to the Bay Area at twelve years old—and is now giving lectures on citizenship and immigration in almost every state but claims roots in Mountain View—could embody the complex, enigmatic, paradoxical notions of what it means to be American.

I see him as a barometer of what America means, in that we haven’t fully developed language or image for it, yet we know it’s true. To honor someone who has so much gravity, resources, and capacity to do work as he’s done—making documentaries for MTV, winning different awards and honorary degrees, co-founding Define American—I placed Vargas’s words on the billboard as the “in-progress” state of what the United States is becoming.

“I’ve been raised inside the legacy of radical education in the Bay Area.”

I get distance on being American by living and working in Seoul, South Korea. When designing the billboard, I would test its affective tenor with international colleagues, to work through tonalities of migration, global capital, and borders: joy, frustration, and how terrifying it is, all at the same time, all the time.

The words of Vargas’s mother, Emilie Salinas, as she said goodbye and sent him to the United States, are at the top line of the billboard. How do these words—of mother tongue, of mother’s love—appear almost immaculately in a space, hovering between the ocean and sky, above our heads and below are feet, guide us through this extraordinary moment in this country and even the world?

POLICARPIO: You often work on long-term, multi-platform engagements that materially take shape as museum and gallery installations, drawings, texts, and projections. These are often undergirded by sustained relationships and trusted bonds with activists, organizers, and community leaders who become collaborators and co-conspirators. Your practice is rooted in these relationships and in research, in collecting and archiving narratives and objects with specific histories and orientations. How are you confronting this political crossroads through this long-game work?

REYES: Born here, in San Francisco, I was on the same sports teams as the kids of the San Francisco State College activists, the same ones you cite. So I have access to guarded conversations and materials that would otherwise be tricky to uncover.

Moreover, I’ve been raised inside the legacy of radical education in the Bay Area. One can make the proposition that continuous decades of social justice in the Bay Area can be traced to the weekday after-school period, roughly 4 to 6 pm. This potentially charged time of day became the prime slot for experimental arts programs of the region’s celebrated nonprofit culture. That’s the proving ground for many educators; it’s unregulated by state standards and when the most fearless curricula are being tested. The after-school programs and services, which many families rely on, often created introductory and necessary spaces for socio-political discussion. It also parallels the time of day when college-student activists and groups gather to plan, after classes, to even be as ambitious as to reshape the infrastructure and pedagogy of their respective institutions, like San Francisco State University.

That’s why my projects end up taking this framework scale, in an era when I think this generation is really equipped with learning how to question and shape institutions.

Formal Ribbon Cutting Ceremony for public artwork Abeyance (Draves y Robles y Vargas), by Jerome Reyes, at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, 2017. With Jerold Yu, Mary Claire Amable, SOMCAN Youth Organizer Alexa Drapiza, Maverick Ruiz, SOMCAN Tenant Organizer Raymond Castillo, Poet Tony Robles, I-Hotel Activist/Historian Estella Habal, SFSU Ethnic Studies co-founder/1968 activist Daniel Phil Gonzales. Photo courtesy of the artist.

POLICARPIO: It also parallels your long-term collaboration with the South of Market Community Action Network (SOMCAN), a nonprofit that organizes immigrant, low-income communities of color for quality-of-life concerns. What interests you, as an artist, in working with SOMCAN, a social-justice organization?

REYES: I am currently a long-term art collaborator there. I teach high-school and college-age students, with the same framework and expansive curricula needed for organizers, who work with solidarity groups negotiating with developers and local government—often with complex discussions about who gets access to certain resources, like who gets to live where. The students have created sincere and even humorous works, including public sound installations, social justice campaigns, printmaking & multimedia workshops, and soundscape laden and skit acted, youth-led audio tours.

With these communities and institutional partners, I strive toward the best scale and conceptual versatility for each contextual situation. This demands project frameworks keeping the personality of a lead artist/educator while providing conditions of success and parallel ownership for everyone involved.

I hope to offer versatile spaces that support the immediate needs of individuals living through these proposed ideas. I’m really invested in how projects reside long term by participants already living complex lives as producers, organizers, researchers, timely visitors, and active locals in multi-vocal, intergenerational communities.

POLICARPIO: For my work, it’s very similar: it’s really about these multivalent connections with people.

REYES: Totally. There’s this pattern of people teaching people: they become older and mentor others, but everyone stays in contact. So you get a greater volume of people learning how to work together and cause needed excitement. I’ve had strong continuity in my projects since I have the same collaborators, some over fifteen years, like the SFSC student-striker-turned-professor, Daniel Phil Gonzales. With every project, the form must be new and energetic. PJ, it’s the same way that I work with you.

I often ask: what is the full potential of your friendship with people? You truly get to know someone when you are both working in the trenches of a project. The best friends I have in the world are people I’ve worked with. People ask me why I have been traveling to Korea for these past seven years; the answer is that I chased a friend. So, what are the possibilities and rigors of friendship in a time when human beings need it the most, in this regional worldview?

tammy ko Robinson and Jerome Reyes. Contact Points: Field Notes towards Freedom, 2006-ongoing. Asia Culture Center, Gwangju, South Korea. Various artifacts amassed from 2006-2016; 40 x 40 feet, displays with various dimensions. Photo courtesy of tammy ko Robinson ϟ Jerome Reyes.

POLICARPIO: I have friends in different institutions around the country. They challenge my thinking in terms of exhibitions, programming, and writing—but at the end of the day, we send [each other] memes and fashion posts. It’s a mix of not only intellectual rigor but also joy and softness—we need those, too.

I know that you are also working on publications and other archiving projects. How do all of these intersecting interests inform one another? How do you decide what form or forms a project will take?

REYES: I’ve had an extraordinary, continuous physical relationship with San Francisco State University in that I went to high school on the SFSU site, twenty-two years ago. My studio holds some of the 1968 archives and more than two tons of historical International Hotel bricks; I have this very material relationship of legacy that I live through.

“I wanted to take the whole spectrum of realities of organizing and protest to where we meditate on how people are imperfect.”

When I exhibit this subject matter outside the United States, I want to show how this tapestry of families—associated by blood, politics, pedagogy, poetics, all live through these potent, globally historical moments and objects and the robust lives they built. That’s why in the archive Contact Points: Field Notes towards Freedom (2006–present)—created by the Seoul-based artist-researcher and professor tammy ko Robinson and me, in the Asia Culture Center in Gwangju, South Korea—one can’t fully separate the music from the time period in which it happened; one can’t split the community programs and health programs away from housing issues; one can’t remove the presence of comic books, literature, and poetry from the labor and student strikes that were happening. They are all lived through the same people.

At times, work in the United States is reduced and read to fit certain genres and practices whereas when the same work is on view in other parts of the world, people understand it more completely. My concerns in shaping projects is to pursue the edges of fullness of a certain context. I have all this volume, and I don’t worry too much since my content often directs the final forms, and this is why my largest projects often take several years.

POLICARPIO: Your work for the Solidarity Struggle Victory exhibition, the horizon toward which we move always recedes before us (San Francisco State Quad), beautifully opens the exhibition and situates the viewer back to the iconic SFSU organizing square. It’s a transcendent and almost otherworldly tribute to the student strikers. I know that this work is part of a larger series of global locales, but can you tell me more about it? Where does the title come from?

“Solidarity, struggle, and victory come with consequences.”

REYES: The title comes from mentor and co-teacher, writer Jeff Chang, who is Race Forward’s vice president of Narrative, Arts, and Culture. The quote comes from the last passage in his recent book, We Gon Be Alright (2016). I wanted to take the whole spectrum of realities of organizing and protest to where we meditate on how people are imperfect, whether it’s concerning different leaders, groups, or disagreements. The tone of Chang’s quote takes a realistic optimism: that we will be alright, despite having to go through yet another wave of injustices.

The drawing in the exhibition is an aerial view of spectators looking down at the platform stage, where events take place daily. However, the architecture was designed to control and disrupt protests. All these walkways go through the quad, so one can’t fully get the attention of the audience. I’ve heard from SFSU faculty members that the building is designed for snipers to be at the top. So, the viewpoint is actually a sinister view that I don’t shy away from.

Solidarity, struggle, and victory come with consequences. People get burned out; they are forever altered by the trauma and fatigue that comes with victory. One can still have the magnificence of a site that embodies and proclaims not only all that ambition but also the realities of that labor.

The fullness of this legacy is fitting for the exhibition, and perhaps we need to ask if these friendships can outlast these movements, to read at the edge of the world with each other, to ask cultural practitioners now who and what they must become as artists, researchers, and global citizens.

Read “Reading at the Edge of the World: The Horizon Toward Which We Move (Part I).”