Last November, I attended a panel discussion, held at LACMA, on photographs of man-altered landscape. The images in question—coolly composed prints by Stephen Shore, Lewis Baltz, and Robert Adams, among others—all hailed from the 1970s. Of all the panelists, only Douglas Crimp had been a full-fledged adult when the images first debuted. The others, including MOCA curator Philipp Kaiser and LACMA’s Britt Salvesen, had still been in the thick of growing up.

The ages of the panelists didn’t seem to matter much until, during the Q&A, a poised student who introduced himself as “born in 1990” commented that, while the photographs appealed to him because of their obvious skillfulness, he wanted to know what someone his age was supposed to take from work created years before his birth. The panelists understandably stumbled—how do you convince someone to value a history he didn’t experience?

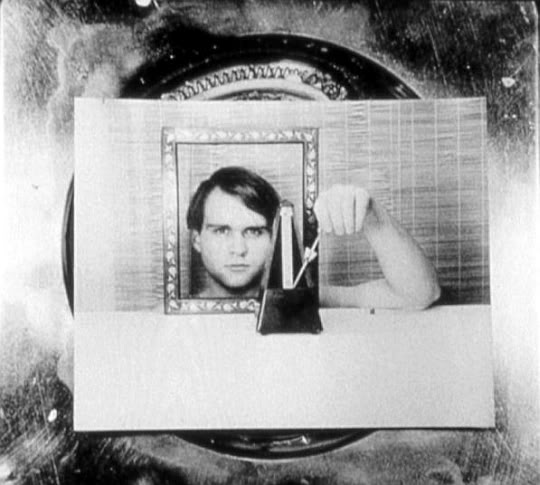

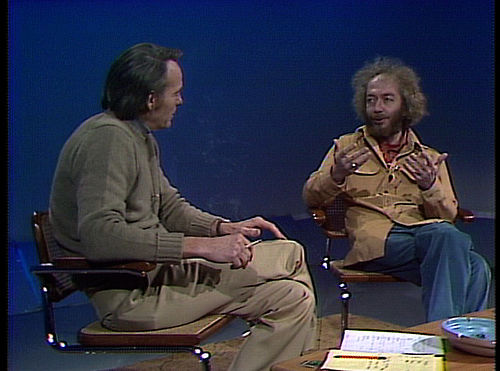

A new screening series featuring the work of experimental filmmaker Hollis Frampton brings this weird tension between the oldness and edginess of “historical” work into exciting focus. Frampton, who began his art-making career as a photographer, made most of his films in the 1960s and 1970s, toying with the physical medium of film as much as with its narrative potential (in Frampton’s Critical Mass, screened last Sunday, a couple quarrels continuously and the breaks, repetitions, and strange overlaps in the frames make human behavior seem absurdly circular–the medium and story are indistinguishable). He also gave incisively smart interviews, and wrote about the practices and ideas behind film-making in a voice that managed to be both theoretically acute and imaginatively candid.

A recent book of Frampton’s writings, collected and edited by Bruce Jenkins, has contributed to an upswing in Frampton enthusiasm over the past two years. During the same time, Los Angeles gallerist Leila Khastoo began considering a potential exhibition of Frampton’s photographs, many of which have never been seen. This proved more difficult than anticipated, since the photographs belonged to public institutions and acquiring them would require a fair amount of finagling. But the process brought Khastoo in contact with Adam Hyman, Executive Director of the Los Angeles Filmforum. Hyman had also been interested in Frampton for some time (Filmforum screened Frampton’s Magellan series ten years ago, but most of Frampton’s work has not been screened in L.A.) and the two decided to collaborate.

“Part of organizing this series is a bit selfish,” Khastoo admits. “Certain films we hadn’t seen sounded really exciting.” And there was the added bonus of a thriving community of Frampton-inspired artists and scholars in Los Angeles. There may not be much explicit or organized conversation about Frampton, but Khastoo sensed an “aura that could be filled up” by something like the film series. So she and Hyman contacted artists, curators, and critics, among them Yvonne Rainer, James Welling, Michael Ned Holte, Alex Klein, and others — all of whom are openly vested in Frampton’s work (some, like Rainer, knew Frampton; others, like Klein, are younger Frampton aficionados)–and asked them to prepare a few thoughts to accompany the screenings. All eagerly agreed.

Hyman, who notes that skilled projectionists are becoming rarer and 16mm screenings harder to arrange (“People don’t learn certain skills and certain ways of seeing anymore,” he says, “and maybe they don’t think that’s important”), sees the screenings as opportunities for those who appreciate the uniqueness of film as an analog medium to experience Frampton’s work as it was meant to be experienced. “The nature of space, the mood and the mystery, it’s different [than other mediums],” he says. And the Frampton films he and Khastoo chose take full advantage of that difference.

The series, titled Circles of Confusion, launched last Thursday with a screening of all-silent films at Khastoo Gallery. That event was full (despite L.A.’s torrential downpour). The second screening, held at the Egyptian Theater in Hollywood on Sunday, January 24, filled up too.

Though I missed the first, I attended the second screening. The crowd, a nice mix between younger and older artists, students, and scholars, started arriving early and was abuzz with Frampton and film-related musings. A few words prepared by the absent Yvonne Rainer and informally delivered by Hyman, followed by an introduction by Erika Vogt, who spoke briefly of her admiration of Frampton the storyteller and Frampton the anti-purist preceded the screening. Then the films began.

During the silent, comically off-kilter Prince Rupert Drops, I could hear the breathing and stomach growling of everyone around me, and could also sense a collective, concerted effort to take everything in. Occasionally, I’d hear the flurried scratch of pencils as people jumped to record images they might not see projected like this again. The two middle films, Critical Mass and Public Domain, were fun, high energy, and laugh-inducing, but it was the final film, Matrix, that excited me most. Like a mix between an over-exposed photograph, a purple-yellow water-color wash, and endless snapshots of pastoral landscape, it was both over-stimulating and under-stimulating at the same time. 27 minutes long and nothing actually happens, except the repetitive progression of over-saturated pictures of cows or grassy fields. Watching it was work , which made me painfully aware both of what was on the screen and of the people around me (were they working too? or had their minds drifted?). For a few days afterward, each time I closed my eyes, I’d see Frampton’s purplish, yellowish matrix.

But my favorite part of the evening? The fact that everyone there came to fully engage Frampton’s work and, in doing so, showed they wanted to understand its history. This, I think, is the answer to the young man’s “what should I take” query: as much as you possibly can.

Peruse the schedule for three remaining screenings, including one this Saturday at Art Los Angeles Contemporary, here.

All films were provided by the Film-Makers’ Co-op in New York.

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog

Pingback: If You Can Remember the ’60s, You Weren’t There | Art21 Blog