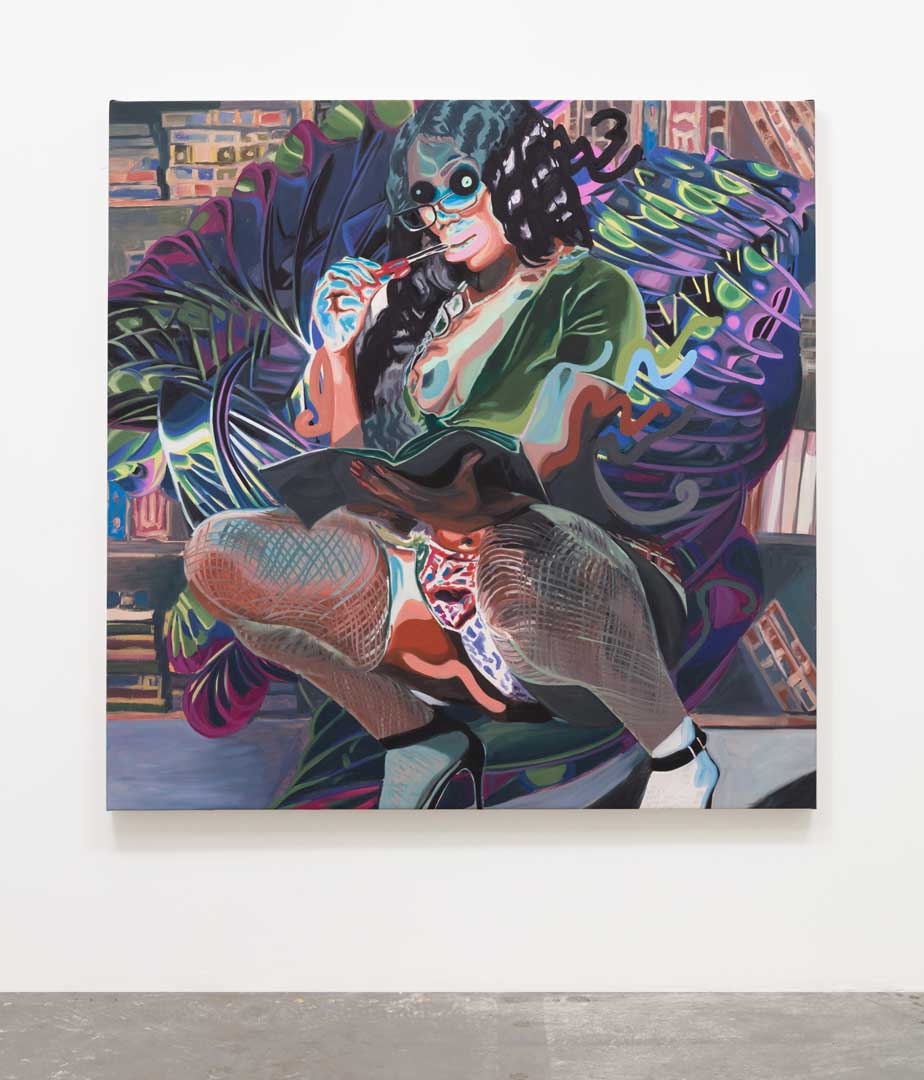

Caitlin Cherry. Ultraviolet Ultimatum Leviathan, 2019. Installation view of Caitlin Cherry: Threadripper, January 12, 2019 – February 9, 2019, Luis De Jesus Los Angeles. Oil on canvas with pencil, 57×101 inches (144.8×256.5cm). Photo: Michael Underwood.

First published in 1985, the essay by Donna Haraway known as the “Cyborg Manifesto” made waves by criticizing the gender essentialism and identity politics of feminism and encouraging people to unite with others based on affinity. It proposes the symbol of the cyborg as a rejection of boundaries “unfaithful to their origins” and that this symbol can help to free people from racist, male-dominated capitalism.¹ The essay also purports that the “boundary between science fiction and social reality is an optical illusion.”²

In the past year, the essay’s post-human politics have heavily influenced my artistic practice, particularly as I build the narratives of the Black female tri-brid figures (merging human, animal, and machine) that I call leviathans, after the mythological sea monsters of Jewish folklore. These painted leviathans are filtered through the backlit glow and glare of current technology, media, and modes of representation—three decades after Haraway created “Manifesto”—but they attempt to illustrate her proposed world of transgressed boundaries and potent fusions.

Caitlin Cherry. Wraith Stealth Leviathan (The Fibonaughti Sequence), 2018. Installation view of Caitlin Cherry: Dirtypower, Providence College Galleries (PC–G). Oil on canvas, 182.8 x 182.8 cm. Image courtesy of PC–G. Photo: Scott Alario.

“Our Best Machines Are Made of Sunshine”

Haraway breaks down the boundaries between human and animal, organism and machine, and the nonphysical and the physical. “Our best machines are made of sunshine; they are all light and clean because they are nothing but signals—electromagnetic waves, a section of spectrum. And these machines are eminently portable—a matter of immense human paint in Detroit and Singapore.”3 Now, in the 2010s, the era of the handheld smart device, our relationship to liquid crystal display (LCD) screens is intimate and fetishistic. For my paintings, I developed a color palette to convey the unpredictable viral behavior of iridescence in a malfunctioning screen: the overexposed inversion of color when a viewer is not positioned optimally in relation to the screen to view its content. My leviathans are married to the technology that my reference material is sourced from (the camera), combined with the medium where I see the reference (smartphone, laptop screen) and who they are as contemporary Black American women, before I transform their images by my style. They are cyborgs of all three of Haraway’s boundary analyses. The “Cyborg Manifesto” charts paradigmatic shifts, from modern to postmodern epistemology. My work exists between two relationships described in the chart: Integrity/Surface and Representation/Simulation.

Caitlin Cherry. Chaos Compressorhead Leviathan, 2018. Installation view of Caitlin Cherry: Dirtypower, Providence College Galleries (PC–G). Oil on canvas, 176.5×218.4cm. Image courtesy of PC–G. Photo: Scott Alario.

Integrity/Surface

An LCD screen is visually immaculate. However, one can break its simulation and reveal its inner world by using a digital camera to take a photo of the screen; the product reveals a representation of a representation. The image degrades into a pattern of streaks that interrupts the image like a digital water ripple. This moiré pattern occurs when the scanning pattern recognition in the camera is misaligned by the pattern of liquid crystals on the screen; liquid crystals are hybrids between solid and fluid states of matter. With oil paint, I render this digital misunderstanding as dark and light bands that veil the primary composition of the painting and create an overlaid secondary composition. The paintings are made of two palettes, of simultaneous over- and underexposure: the metaphor of the plight of Black women in mass media. I affectionately refer to this overlay with the term pictorial spaceX, to evoke the paradigmatic shift of the picture plane of a painting as a screen. The light and dark banding system does not represent the sun streaking through some architecture but rather a backlit determinant.

Caitlin Cherry. Sapiosexual Leviathan, 2018. Installation view of Caitlin Cherry: Dirtypower, December 5, 2018 – March 2, 2019, Providence College Galleries (PC–G). Oil on canvas, 72 ½ x 72 ½ inches (184.2 x 184.2 cm) Installation view image courtesy PC–G. Photo: Scott Alario.

Representation/Simulation

My painted leviathans originate from images of Black American women who participate on some level in the sex industry: porn stars, Instagram models, C-list rappers, and A-list celebrities with histories as exotic dancers. Their livelihoods are least dependent on the whims of white popular culture and as a result they have crafted identities or brands that are extreme and unapologetically Black. These women decorate themselves with multicolor wigs and visible tattoos once deemed too “ratchet” for professional contexts but have now been appropriated by young white urbanites working in creative industries. The women have enhanced their bodies through plastic surgery and have become, in a way, more than human. These women buy into a liberated, sexualized image that takes the stereotype of the hyper-sexualized Black woman to its limits. Nevertheless, they are successful and—like Blac Chyna and Cardi B, whose net values are in the millions—capitalize on a lineage that recalls the aggressive, hardcore style of Lil Kim, the popular rapper of the late 1990s and 2000s. Together these Black women have fundamentally changed beauty trends, reaching outside the Black community to become global cultural exports. Within the Black community, their rise to stardom is a vice for their potential to influence young Black girls away from supposedly more dignified and respectable paths. I refer to and paint these women to elevate them to the highest levels of grace and grandeur that can be achieved through the revered medium of oil paint. Though the careers of these women may be short explosions, oil paintings have long lifespans.

“When my identity is mistaken for that of my subjects, our personal histories are flattened.”

At my art openings, I have been mistakenly identified as the women in my paintings by gallery-goers, curators, and critics, which risks turning my investigative practice into a series of self-portraits. Since painters tend to leave bits of themselves in their works, this is not an unfounded observation, but it is inaccurate. Yet it furthers the tension between representation and simulation that I tackle in the work. As a curvaceous Black woman with mint-green hair and visible tattoos, I share aesthetic characteristics with these women, and I take observations of these affinities as compliments. But I have never been a dancer, rapper, or model; I am a visual artist and a professor. When my identity is mistaken for that of my subjects, our personal histories are flattened. I am interested in the mythmaking, insofar as it helps to break simple stereotypes and to complicate who Black women are or might become.

Caitlin Cherry. Innversion, 2019. Installation view of Caitlin Cherry: The Armory Show (Focus Section), March 6, 2019 – March 10, 2019, Luce Gallery, Turin, Italy. Oil on canvas, 69 ½ x 86 inches (176.5 x 218.4cm)

Mythmaking

In the “Manifesto,” Haraway defers to the professor and postcolonial feminist theorist, Chela Sandoval, who describes the condition of being a Black woman as being at the “bottom of a cascade of negative identities, left out of the privileged oppressed authorial categories called women and blacks.”6 We who are Black women essentially transgress femininity and Blackness. Black women end up fused to an entirely new identity. Black womanhood is an unsolvable equation that reminds me of the “three-body problem” of physics.5 In this problem, three celestial bodies in trajectory with one another will forever have unpredictable paths. If two of these bodies find balance, the third will unexpectedly yank the first two out of sync, and their orbit becomes chaotic once again. The three bodies can easily be seen as metaphors for the identities of Blackness, womanhood, and class—identities that can never merge nor fully be oppositional or unified forces. This metaphor could be helpful to animate the socioeconomic tension of the buzzword intersectionality, particularly when applied to the identity and the culture of Black women. This metaphor proposes post-intersectionality, assuming that the three identifiers have positions that are expected to cross each other. But in contrast, and in reality, they are in a constant, chaotic recalibration between each other, perpetually reshaping the definition of each identifier.

Conclusion

Donna Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto” has a persistent influence on us humans/aliens who are fans of futurism, left accelerationism, and cyberfeminism. But it also has a deep effect on anyone frustrated with the snail’s pace of feminist progress in America. Since the essay’s publication in the 1980s, the text remains quite relevant despite technological advancements in society. It has also ignited interest among a younger generation of scholars and thinkers.6 Although my artistic practice has a plethora of influences and an encyclopedia of content, I feel that none are as nourishing as the “Cyborg Manifesto.”7