Jason Peters at his studio in Salina Art Center.

Jason Peters is an artist based in Brooklyn, New York. Over the years, he has discovered his muse in found objects – whether they are tires, buckets, or another material that allows him to manipulate it in vast quantities. He is a builder, a maker, and a worker who often turns trash into precious and delicate structures by using modular elements, which he then interconnects like building blocks to create entirely new forms. Peters’s large organic, illuminated structures are playful and light. Somehow they seem easy, as if the artist simply gestured with his hands in space.

I’m rarely drawn to works that seduce my eyes and I never quite trust them, but in Peters’s case, there is a quality that made me reconsider this. It can easily happen to you too, if you view one of his light sculptures in person. You’ll instantly feel like you’re 5 years old all over again and carefree. You would not realize it right away, but after a few moments passed, you’d be able to hear yourself softly gasping with astonishment. You’d be convinced you’re inside some computer game, where a suspending glowing structure is shapeshifting as you walk around it.

Today I’m introducing you to Jason Peters. Let’s consider the limitations an emerging sculptor is faced with early in his career, and how these limitations currently work to his advantage.

Georgia Kotretsos: How important is having a studio for your practice?

Jason Peters: To begin with…having one would be nice but not having a studio has never stopped me from creating work. It was a combination of things in college, where I first began making large works – realizing that material manipulation comes at a cost. This is when I started using found objects in large quantities.

As this process evolved, I had no desire to accumulate or store materials. I only wanted to build the sculpture, document it, and move on to the next project. Also, I had nowhere to store my work or [sustained] interest in it per se, because the art market hadn’t yet value assigned value to my work. So I would either throw the works out or I’d put them back where I had found the materials in the first place – in the trash.

As an artist, I feel that the potential to create is within oneself. The times I had the opportunity to work at a studio were due to being an artist-in-residence. It has been great because it allows me to create 2D works. Being able to create without worrying is a wonderful thing.

Jason Peters, "Untitled," 2009. Drawing cutouts, 19 x 20 inches.

Living in Brooklyn, NY, I have a 40-60 hour-a-week fabrication job, which is how I survive. I have a place in my house where I make work, but it is not a studio setting. I make work when I can, and I do not particularly worry about making work all the time, since some days I get close to making a work and others I feel like I could lose my mind.

GK: Basically, you’re telling me you create in-situ installations, which are built directly on-site. Where do you usually show? What are the conditions that allow you to work at a given location each time?

JP: My works are the products of a systematic process consisting equally of conceptual, formal, and practical elements. I show at places that want to give me a chance. My first large-scale project was at the Center for Contemporary Arts in Santa Fe in 2004. It was my first self-produced solo show. I was brought there by the curator, Kathleen Haniggin, on whom I relied heavily to help with gathering access to materials and volunteers. I went there with a few ideas, but I knew that all could change depending on the material I would find (which would dictate what I could build). The works I build are site-specific because I rarely move any of them around. Recently I did [move my work], for [a project at] The Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts in St. Louis, MO; I will talk about that later on.

Basically in Santa Fe, I came across buckets driving through the countryside. What is curious to me here is that I had chosen to collect 400 buckets, while somebody else had decided to thrown them out.

One person’s trash is another’s treasure. Having found my material under time constraints, a toy I played with from my early childhood came to mind. Remember those wooden snakes that you held by the tail and they moved? Well, the inherent properties of the physical shape of the bucket contributed to the creation of the first bucket piece. This show was entirely possible because someone offered me the space and invited me to create a sculpture – it was an opportunity to manipulate space.

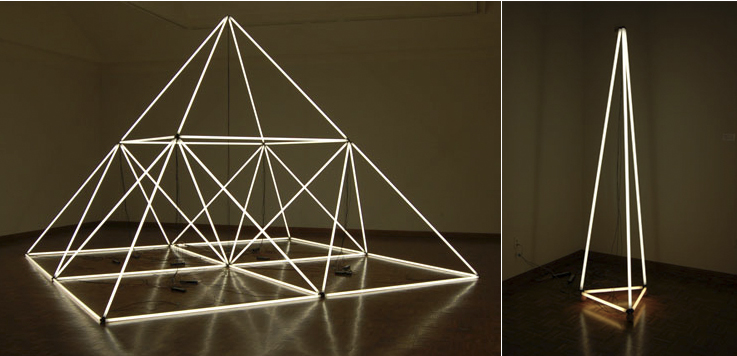

In 2006 at the Mattress Factory, I was given full license and funding to create anything I wanted. The environment that Michael Olijnyk and Barbara Luderowski have created is amazing and [it] allowed me to grow and evolve by [enabling me to] make my first light sculpture (structure). I came up with a simple solution to highlight my initial material by presenting it floating in negative space. I figured if I lit the work from the inside and created a black room (background), I could remove it from the site itself. This gives you an experience but also make you aware of your other senses by default. Somehow the illusion of infinite space is created, which further impacts viewers emotionally while they remain physically grounded.

For instance, when working with White Flag Projects in St. Louis, MO in 2008, Matt Strauss gave me only two weeks to install a two-day show.

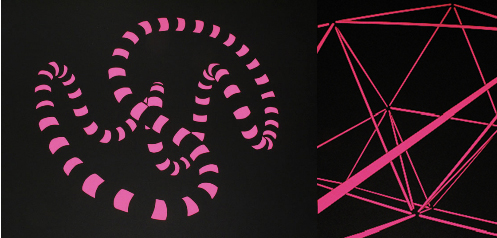

Jason Peters, "No More No Less," 2008, at White Flag Projects, St. Louis, MO.

Most would say that was crazy for a 3000 square-foot space. The show did happen somehow and I was very pleased with the direction and the dimension my work was taking at the time.

Jason Peters, "No More No Less," 2008, at White Flag Projects, St. Louis, MO.

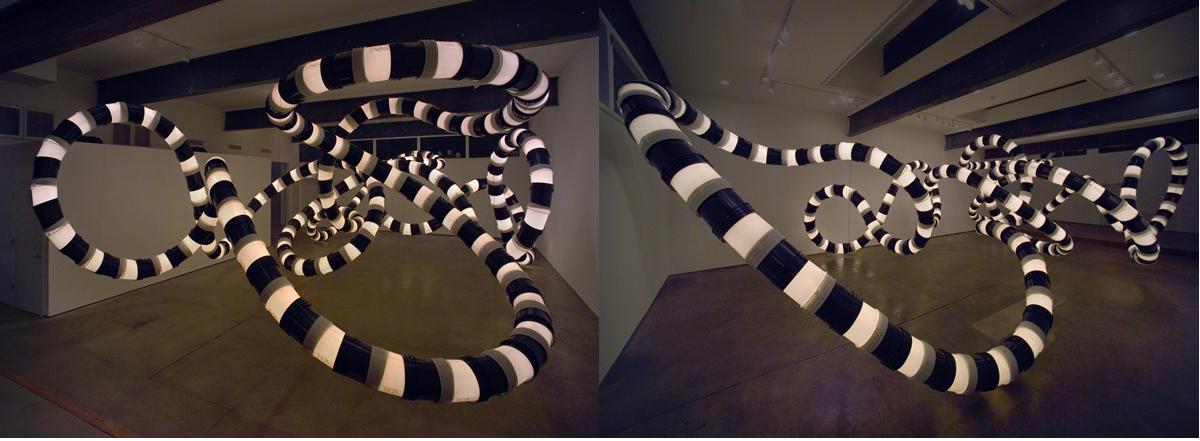

To this day, the Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts has given me the biggest opportunity. I created a light sculpture in a 20,000 square-foot field for a show entitled The Light Project (2008). The challenge was, how do I build something that does not look like we just plopped a sculpture down on the lawn? It had to compete with the buildings around it, and I needed to construct a structure of some sort to support the light piece. Since I had always loved scaffolding, I incorporated it into the piece to facilitate my artistic needs, by building a 32 x 32 x 24 square-foot structure to juxtapose the curvilinear and linear elements against each other.

Jason Peters, "The Light Project," 2008, at The Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts, St. Louis, MO.

Before I can get to this point, the most important aspect of my work are the people who come forward to volunteer by assisting the making of each work. Without them, nothing could be done.

I usually have tons of ideas; I think most artists do. But time, money, and opportunity do not always align perfectly or simultaneously. I could always have more of everything, but I like to start with what can I get. Donations of materials are always of great help, since that is half or more of any budget for a show. What I have learned is to find the boundaries of what is offered to me — in terms of money, time, and space — start with what I have, and adjust the project to each set of limitations. It is the worst when you are shot down at every turn, so I now ask, “What are you willing to donate?” I have always made what I wanted and I feel my work represents me in the best light. Nonetheless, without thinking twice, I would never undertake a project if I thought it could not be done within reason, or if insufficient support is offered while unreasonable expectations are projected.

GK: You live and work in New York. Do you feel like a New York artist? What does it mean to you to identify as one?

JP: Most of my shows have been outside of NYC. What is that label really all about? Most artists are from somewhere else; NYC somehow makes us look better on paper. Personally, I grew up in Munich, Germany, and once I was finished college in Baltimore, I had to go somewhere and NYC was the city on the East Coast. So I moved here and am giving it a shot. It has now been 10 years and counting that I’ve lived in NYC. Only now do I call myself a New Yorker: a New York artist, more so than an artist living in New York. The competition is crazy; NYC has so many artists competing for the same venues, it’s like Rome during the gladiator days. And more keep coming. I think you have to have a really thick skin and the mental capacity to enjoy this kind of challenge.

When people ask whether I like being there, I [tell them I] cannot see myself anywhere else at this point; I love it here. What I have created is a great network, which in the end will pay off. I have established my sources; I can find and get anything at a moment’s notice either on the street or from a supplier. I can leave the city when I want, and for any period of time. I can always find someone to sublet [my apartment] and cover my costs when away. I always have a job when I get back and I can make a good living when I am working for others. The goal, though, is to make a living from my work, which I will see in time.

For me, this city is the one of the most amazing place I have ever visited; I just have to watch out and take care of myself. It is a city where anything is possible; it is what you do which makes it so — or not. I would not be where I am today if I hadn’t moved here. The city has affected me. I feel like an artist first and foremost, and I would be one anywhere else I would have chosen to live. NYC is just a location — expensive, yet filled with potential.

GK: Where would you ideally like to install one of your pieces?

JP: The ideal place would be an interesting and challenging one. I am attracted to spaces that have a powerful presence. Some are naturally lit and others are artificially so. Spaces where things are maybe not expected to be. For example, when I was approached by the Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts to do a piece, they said it has to be in this place ,which was a 150-foot by 120-foot field. It would not have been the space I would have chosen, but it pushed me to do something I had never done before — which I am grateful for.

Places that have inspired me are: interiors of churches, rooftops, billboards, and shipping container boats or the lots that store the empties (like the exit in Jersey off I-95 going into the Lincoln tunnel). A space that has intrigued me a lot is the atrium of MoMA. The museum has so much space, but the biggest is the multi-story space in the heart of the museum that has not been yet challenged with a work of art. It would have to be huge to have an impact on the space.

GK: What are you working on now? Where can we find your next installation?

JP: Currently, I’m an artist-in-residence at the Salina Art Center in Salina, Kansas.

Jason Peters's studio at the Salina Art Center.

I have made a lot of 2D work for the first time [in a while], so I am going to continue with the drawings I have been making. I have made 20 drawings so far and will see if I can find an exhibition opportunity for them — likely in the fall.

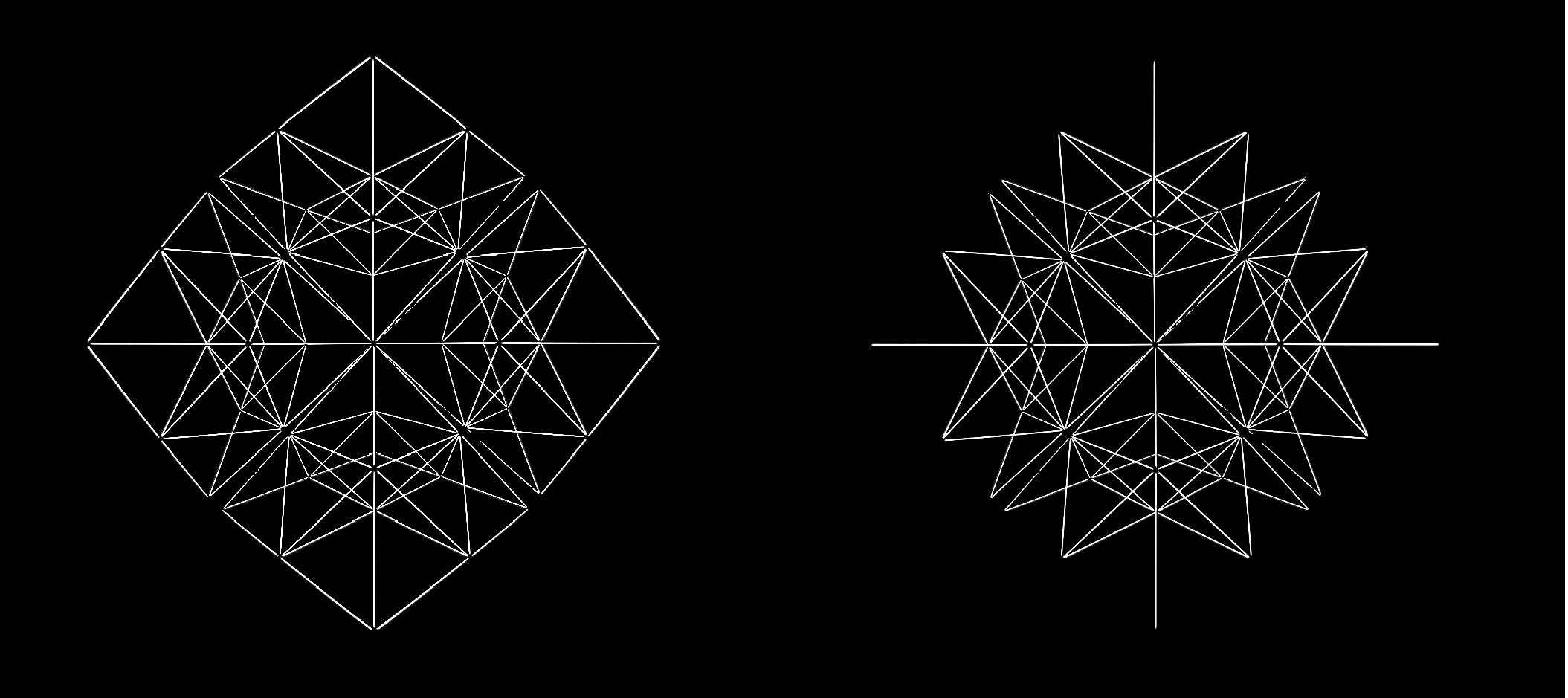

Jason Peters, "Untitled," 2009. Drawing cutouts, 19 x 20 inches.

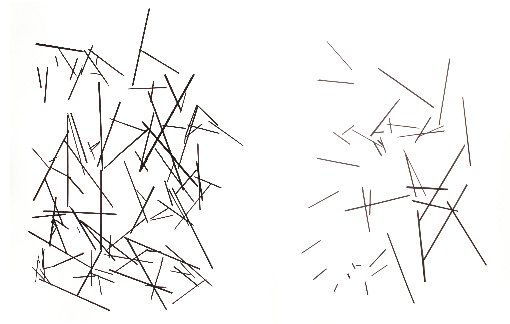

Left: Jason Peters, "Crossing Paths," 2009; Right: Jason Peters, "Captive Muse," 2009.

I have applied to a lot of programs, so I will see if anything comes through. The next major installation series is for a solo show entitled Anti. Gravity. Material. Light. at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art in late January-April 2010. They have given me a 6000 square-foot gallery on the first floor, allowing me to make a sizeable work, or perhaps several. We are currently figuring out the exact layout. Then I am going to Sculpture Space in Utica, NY, for February-March 2010 to make some more new work.

Jason Peters, "Untitled," 2009. Drawing cutouts, 20 x 32 inches.

###

I have no doubt I will be talking to Jason Peters again in the near future. Engaging in conversation with the artists I’ve introduced you to so far helps me maintain my sanity as an artist. I’ve always needed this kind of dialogue for my own practice, and doing so from here makes it even more valuable.

And that’s a wrap!

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog

Pingback: New Frontiers | Jason Peters, Anti.Gravity.Material.Light | Oklahoma City Museum of Art