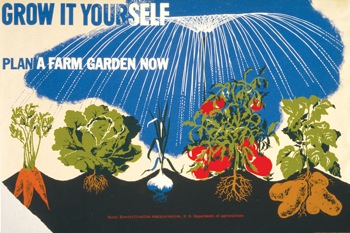

Herbert Bayer, "Grow It Yourself: Plant a Farm Garden Now," ca. 1941-43, New York NY. Silkscreen on board, WPA War Services. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, WPA Poster Collection.

Gastro-Vision is a new monthly column dedicated to all things food.

It probably goes without saying that depictions of food in art are as old as art itself. Since the prehistoric cave paintings of bison, deer and other fodder, food has permeated all forms of cultural production and continues to be subject and/or material for countless artists and artisans today. Over the past year, a few of our guest bloggers have (unknowingly) given you a taste of what Gastro-Vision is about. Taking food and drink as a jumping off point, Sarah Silwa wrote about the Body Bakery of Thai artist Kittiwat Unarrom, and listed a few other artists known for their use of sugars and starch, such as Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Joseph Beuys; Paul Schmelzer profiled artist Chakkrit Chimnok in his post, “Banana-Leaf Utopia“; and, most recently, Tracy Candido outlined economic models for arts funding and fundraising, citing new ventures like her own bake sale artist residency, Sweet Tooth of the Tiger. Gastro-Vision seeks to continue and expand on such contributions while making connections to broader topics in contemporary visual art and culture.

Readers who follow my personal blog know that I have become increasingly interested in what goes into my food and where it comes from. (I probably owe this to food writer Michael Pollan, whose books The Omnivore’s Dilemma and In Defense of Food, and soothing voice in the “civilized horror movie” Food, Inc., have helped open America’s eyes to problems with our food system and subsequent eating habits). The more I learn, the more motivated I am to eat as close to the bottom of the food chain as possible (i.e. increasing my consumption of locally grown plants). But New York City certainly has its challenges when it comes to finding (and affording) good local food. Hence, the rise of urban farming. Three new visual and edible projects—Truck Farm, Welcomed Guests, and Window Farms—reflect this trend, presenting resourceful methods for growing your own food in the metropolis and, what’s more, sharing it with others.

Documentary filmmakers Ian Cheney and Curtis Ellis, known for their 2007 award-winning film King Corn, have converted the bed of a 1986 Dodge Ram pick-up truck into a mobile garden. Both a summer food project and film, Truck Farm, combines green-roof technology, organic compost, and heirloom seeds, bringing fresh food wherever these guys may drive. In a Tasting Table article, Ellis said, “[The film] is partly about bringing locally grown fruits and vegetables into all neighborhoods, but it’s also a wild-and-wooly romp through this new world of the urban farmer.”

Just look at their luscious green rows of…well, what is that? A few weeks ago, Ellis (dubbed “the four-wheel farmer”) posted to the Civil Eats blog:

Four months [into it and] we’ve got ripe tomatoes growing in the bed…The gray Dodge has already given us a bumper crop of arugula, lettuce, broccoli, and herbs, and our habañero plants are rooting nicely. Most importantly, Truck Farm is sprouting a steady supply of interested neighbors. They pull weeds, add water, only occasionally steal parsley, and leave behind a calling card of plastic animals: toy cows and chickens that graze contentedly among the nasturtiums. Part garden, part art installation, Truck Farm is getting invited to way more summer barbecues than its owners.

The social value of Truck Farm is evident: the model brings us a teeny step closer to a more just food system, in which good, whole foods can be grown and easily distributed where they are needed. It also broadens the possibilities for ownership of “farmable land.” But having described the piece as an art installation, I wanted to hear more about the farm’s aesthetic growth, so to speak. In a recent e-mail, Ellis and Cheney had this to say about Truck Farm:

It wasn’t our idea to think of Truck Farm as art; it really sprang itself on us that way. When we started the project, we just wanted to grow food in a pickup. That was partly for reasons of activism (wanting to encourage conversations about healthy food access issues and wanting to show people how easy it is to grow your own food), and partly just because we wanted something good to eat ourselves, and that was the only land we had. But once the seedlings sprouted, we realized there was something really beautiful about it. In a rusty gray pickup, against a backdrop of gray asphalt, this green shock of life was breaking out.

As the vegetables in the truck have grown, we’ve been documenting their progress with time-lapse photography. Ian built a solar-powered camera system in the cab that takes a photo every five minutes, and in the footage you can see the way these supposedly inert things we eat—lettuce and broccoli and tomatoes—are very much alive. Matthew Moore is an artist in Arizona doing some wonderful work like this, and he comes very clearly from an artist’s background, while we started more as activists and worked our way over toward art. If art is something that helps you see the world you live in differently, that’s what the time-lapse helps to do. By collapsing the weeks and months of a growing season into a minute or two, you suddenly see just how much work those little plants are doing every day.

We want Truck Farm to be a kind of public garden people can interact with. There’s all this unused open space in New York—rooftops, vacant lots, parking spaces. We want Truck Farm to remind people that those are spaces we should reclaim. The city should be beautiful, even in its most utilitarian corners.

To be continued…

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Gastro-Vision: Aesthetics of Urban Farming, Part II | Art21 Blog

Pingback: Reader August 26, 2009 « updownacross