[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2CqTsHQ78U]

With the haunting mix of bodily certainty and existential confusion that characterizes a case of morning wood, the naked, supine torso of Ed Harris comes to sudden erection in a primeval forest, shooting up into the verdant frame like a rake that’s been stepped on. The shot is a crucial one in the opening sequence of George A. Romero’s Knightriders. The precipitousness of the montage conjures up both the identification of man and nature, as figured by Harris’s out-of-body “crow’s eye view” flight through the forest as well as his sudden awakening to the central conflict between the Rousseauist utopianism of the merry band of Medievalist motorcyclists he leads versus the alienating threat that modernity and capital pose to their way of life.

While this image may seem an unlikely entry point into the Grand Canyon, the proliferation of Arthurian place names in the Canyon (Excalibur Tower, Modred Abyss, Lancelot Point, Holy Grail, Gawain Abyss, Bedivere Point, The Dragon, Guinevere Castle, Merlin Abyss, Elaine Castle, and Galahad Point) speaks otherwise. Moreover, Ed Harris’s ontological sit-up echoes the axial leap of the horizontal geological striations that spatialize time along the canyon’s walls to the arbitrariness of the names (an arbitrariness that we will hungrily feast upon) that identify vertical rock formations and voids.

Let us rewind for a moment to the Edenic state of nature envisaged before “the rise” of Ed, if you will. During the “crow-cam” sequence that opens Knightriders, we can now imagine Ed Harris lying down naked, out of frame, presumably asleep or dreaming on the forest floor. In this as-yet-unseen state, the Ed Harris-to-come is a kind of pure potential, a horizontal being that has yet to emerge from the plenitude of the forest. This avatar of Ed Harris finds his mirror image in the horizontal geological strata exposed on the walls of the Grand Canyon. Whereas Ed, in his latent form, is being as pure potential, the spatialization of time and temporalization of space that characterizes the geological stratum make it a crucible for the materialization of being as history in which space and time are co-extensive. In the layers of the Grand Canyon, space and time refine and compress one another. Being travels further and further away from pure potential until it almost sublimates into it; hence, the feeling of irreality that, like the veils of smog that descend into the chasm during peak season, tends to both intensify and obscure the experience of the Canyon.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=drHuy-1xuBQ]

What does it mean to point to time? Could we point to the Middle Ages on the geological calendar wall of the Grand Canyon? Does the tip of Excalibur Tower, which is said to look like King Arthur’s legendary sword, contain the moment when its namesake was thrust into a soon-to-be-slain dragon? Does Guinevere Castle house a temporal room in which the Queen scandalously gave herself to Lancelot? The answer is no, since even the uppermost strata of the Canyon are approximately 200 million years old. Kim Novak’s character from Vertigo would have to ethereally drive a few hundred miles away from that ringed redwood in order to ethereally point to a time that would approximate that temporal distance.

In fact, the Arthurian formations of the Grand Canyon have nothing to do whatsoever with the horizontal geological record. Instead, these knights were dubbed in 1902 by a pernicious power vested in a United States Geological Survey cartographer named Richard T. Harris. That power, which was a purely vertical power, was resemblance. Thus, when trying to locate the medieval period at the Grand Canyon, the enigmatic finger of Kim Novak is replaced with the bathetic finger of Monica Vitti pointing not at the material manifestation of time, but outside the frame of a photograph (and a sort of silly colonialist, travel photograph at that). Resemblance and Orientalism govern the proliferation of place names that seek to identify almost every geographic feature of the Grand Canyon. This is vertical territory. Under the banner of one big, dumb place name, a million more march in to lay claim to every stone and even the voids between them. This is the world that Ed Harris wakes up in.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VvWlAumjyuI]

Resemblance is the castle whose walls Ed Harris must scale to redeem his people and return them to a life of horizontality and because I really want you to see this film, I won’t tell you what happens in the end. A few key points though: despite appearances, Harris is less invested in appearances and more committed to the radical transformation of society through ancient rituals of life and death on two wheels. And while Knightriders never travels to Las Vegas itself, the insidiousness of appearances and resemblance is figured by a sleazy agent named Joe Bontempi who “books Vegas mostly” and tries to lure integral members of Harris’ group—which is more like a carnivalesque, mobile, communal society—away from their epic spiritual journey to a life of commercial performance.

Like a desert on the edge of an advancing spiritual abyss, this fragile community must defend itself against the infectious logic of Las Vegas. It is no coincidence, then, that there is an Excalibur Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas and that I found myself staying in the belly of the beast on my way to the Grand Canyon a couple weeks ago. Some other Bontampi has gathered an army of medievalist performers who deliver sanitized and spectacularized dinner theater while down the hall, some other Eds invert the Harris paradigm by taking off their clothes for money instead of putting on their armor to stay poor. This all makes me take comfort in the many magicians who have found a home in Vegas. Perhaps it is they who are charged with defending being for now.

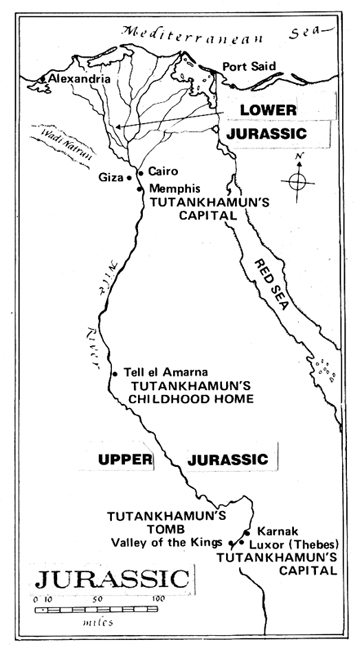

Next time we will compare the work of magicians and contemporary artists in Las Vegas with special attention to David Copperfield’s use of video and Maya Lin’s new commissioned sculpture of the Colorado River at the Aria Hotel. But before we go, I’d like to share a bit more geological magic that I experienced recently in Los Angeles. A couple of years ago, I investigated the play of space, time, and sedimentation at work in The Museum of Jurassic Technology for The Journal of the Valkenberg Hermitage. The museum, which is one of the only institutions I know of that is wholeheartedly dedicated to the diffusion of horizontal knowledge, cleverly traces its lineage to “the Lower Jurassic,” the geological time period which the Museum’s materials suggest is the geographic region of the Lower Nile River Valley or northern Egypt. This spatio-temporal confusion serves to extend the horizontality of the Museum, a movement which extended right into the performance of several medievalist compositions of the seventeenth-century composer Henry Purcell by The Agave Baroque Ensemble in the Museum’s “Tula Tea Room,” which I had the privilege of experiencing recently. Their performance of King Arthur in particular made me want to hear a harpsichord resonate through the void of Merlin Abyss.

Another bit of magic that’s native if not endemic to Los Angeles is all the “acting” going on around us here. Perhaps it is the magic, not just of cinema but of acting itself whereby Ed Harris (who you’ll notice I’ve referred to consciously by name throughout this post in order to get at the perverse way in which, to use a vulgar cinematic formulation, his characters become him), who rises in the forest to rev his motorcycle engine, bringing nature and culture into a striking synthesis, becomes another Ed Harris who is after an eerily similar synthesis, but gets famous for taking stuff off the ground and making it vertical despite the fact that he can’t ride a bike for shit.

[youtube:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fZZyx4LvLVY]

Pingback: What’s Cookin at the Art21 Blog: A Weekly Index | Art21 Blog