Exhibition work attracts people from a range of backgrounds, but it now has its own institutionalized forms of training. As graduate schools increasingly offer specialized degrees in curatorial work, museum studies, and arts administration, we might ask what sort of knowledge goes into the creation of an exhibition. What skills are specific to gallery or museum jobs and what overlaps with other disciplines? This week, Open Enrollment looks at the subject of “the exhibition” from two adjacent fields: art history and business. Oliver Wunsch considers the role of exhibition work in an art historical education by looking at MASS MoCA’s current show InVisible, curated by one of his classmates. Mike Brenner discusses different cost structures of grassroots art exhibitions, and how changing economic times force artists to adapt to find space and funds.

PHENOMENOWHAT?

by Oliver Wunsch

In my first few visits to MASS MoCA‘s current exhibition InVisible: Art at the Edge of Perception, I missed the first work of art. Katia Zavistovski, the exhibition’s curator, eventually corrected my obtuseness. She directed my attention back towards Karin Sander‘s Wallpiece (2010), a 60 x 36 inch section of polished paint on the far wall.

Katia is my classmate in Williams College’s History of Art graduate program and it is easy to put our academic minds to work as we stand in front of Sander’s piece. I began to pontificate. Does the subtle reflective quality of Sander’s square insist on the phenomenological nature of viewing? Or is it a semiotic critique of the codes and conventions that normally separate art from its context?

This language may sound more appropriate for an academic paper than a blog post and I promise to keep it under control. The bigger question I wanted to address with Katia was whether this type of discussion belongs in museums.

Graduate students at Williams have plenty of opportunities to get out of the library and go to work on exhibitions. The program itself is based in the Clark Art Institute, which combines a museum and research center in the same building. Students can also take work-study jobs at the Williams College Museum of Art and MASS MoCA, both of which provide the chance to curate shows.

The Two Art Histories, a book based on the 1999 Clark conference examining the "tense relationship" between museum and university-based art historians.

Like Katia, I work at MASS MoCA and will organize an exhibition there next year. My time at the museum gives me a welcome break and sense of distance from my academic work. Still, this same feeling of separation makes me wonder how curatorial work fits into a graduate education in the history of art, if at all.

I never noticed much of a divide between these two worlds until coming to graduate school. Since then, I have heard a lot about the “two art histories,” one that exists in museums and the other in colleges and universities. In the most extreme version of this rift, academics see the museum as tainted by financial interests and associations with mass entertainment, while curators view the academy as blind to actual works of art.

This division creates some problems for a young student of art history. For instance, my classmates who hope to eventually work in a museum find that they need to carefully frame their professional ambitions when applying to PhD programs. Even those who hope to become professors have to figure out how to discuss previous curatorial work when crafting their intellectual biographies. If the boundary between the museum and the university is so professionally entrenched, then can a student productively move between them?

In Katia’s case, at first I had trouble making connections between these two places of work. Her qualifying paper (the Williams equivalent of a master’s thesis) deals with the grizzly morgue photographs of Andres Serrano. Flayed corpses and scorched flesh don’t quite fit in the serene atmosphere of InVisible. White is the show’s dominant color, not red. When I stand in front of Christian Capurro‘s Compress Series (2006-2008), a group of magazine pages whose surface the artist has nearly completely erased, I want to get closer and decipher the slight gradations of tone. When I saw Katia present a version of her Serrano paper this fall, I wanted to run for the bathroom.

In that sense you could say that InVisible and Katia’s academic work share an interest in our sensory limits. They both insist on an affective experience of art, albeit at two different extremes. When I asked Katia whether any of her studies at Williams had influenced the show, she talked about reading Maurice Merleau-Ponty‘s writing on the nature of perception during our first-semester seminar on the methods of art history.

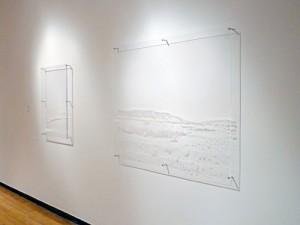

The French philosopher certainly came to mind when I looked at Joanne Lefrak‘s Trinity Site series. Lefrak etches lines in sheets of Plexiglas that she then mounts about an inch off of the wall. The picture that she draws in the transparent surface only becomes visible as light flows through the glass, causing the semi-opaque scratches to cast a shadow. It all reminded me of Merleau-Ponty describing the experience of swimming and looking at the tiles on the pool floor through the reflections of water. He notes that his perception of the tile and the watery play of light are inseparable from each other.

Students of art history read Merleau-Ponty under the banner of “phenomenology,” but that word never appears in any of the InVisible show materials. Katia explained that she included it in an early draft of the exhibition brochure, but later took it out at the suggestion of other people at the museum. The issue of audience clearly separates the “two art histories.” Text that makes sense in a conference paper may be of little interest to most visitors of MASS MoCA.

My attention to the show’s brochure may be heading off course, since an exhibition ostensibly speaks through the arrangement of works of art. That fact may be what separates the museum from the university more than anything else. The devices that a curator uses in hanging an exhibition don’t have much in common with the academic’s faithful tools of argumentation: Microsoft Word and PowerPoint.

Jaime Pitarch's "Preliminary Drawings for a Show, Erased" (left) and an untitled fabric piece by Janet Passehl (right)

All of these tools come with their own dilemmas. When walking through InVisible, I asked Katia to talk about the role of the glass display cases in the show. I noticed that a vitrine protects Jaime Pitarch‘s Preliminary Drawings for Show, Erased (2006), so you don’t get much of a look at the artist’s blank sketchbook (the title should explain the blankness). In contrast, the delicate fabric pieces of Janet Passehl remain exposed to the air.

Katia defended the choice, noting that the glass over Pitarch’s drawings makes them even more invisible because it keeps the viewer from flipping through the sketchbook. Passehl’s piece, on the other hand, depends on the tactility of the fabric and a clear view of its subtle folds.

Still, the answer did not entirely satisfy me. In an effort to rub the “two art histories” against each other, I began to indulge my academic imagination. Invoking Merleau-Ponty, I told Katia that I couldn’t separate my perception of an artwork from the glass that stood in front of it. Within a show about the edges of perception, doesn’t glass itself become a charged medium? Amongst works that challenge the visibility of art’s borders and interrogate the ontology of the frame, doesn’t the vitrine itself become a questionable device?

Katia offered two more justifications that were harder to refute: insurance waivers and contractual obligations to the owners of the work. No amount of phenomenological theory could change that.

CHANGING ECONOMIC TIMES FORCE ARTISTS TO ADAPT

by Mike Brenner

When Milwaukee hosts its quarterly Gallery Night, thousands of people descend upon the city’s historic Third Ward. It’s one of those neighborhoods that 25 years ago people were afraid of. When galleries and theater companies started to move into this neighborhood anchored by my alma mater, the Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design (MIAD), so did the restaurants, bars, and high-end retail. Now everywhere you look, there are cookie cutter condo developments popping up, and in the last ten years, rents have soared to a point where only a handful of galleries can still afford to stay in the area.

In 2000, a group of MIAD students started doing a series of installation-based shows, they called Rust Spot, in one of the many empty warehouses in the Third Ward. The local business improvement district got them the space for free, and they were given carte blanche. For three years, the group put together some of the most exciting shows in the city. These one-night exhibitions drew in over 2,000 people every Gallery Night, until the space became more valuable to a local real estate developer sitting empty than as an incubator for exciting, fresh art.

Around the time Rust Spot was evicted and empty warehouse space started disappearing, the nonprofit I was running, the Milwaukee Artist Resource Network (MARN), started an exhibition series called Destination. MARN would find a local business that saw the value in having artists in an otherwise unused space, and then MARN’s board of directors would jump through all the bureaucratic and financial hoops of getting a temporary occupancy permit ($200), event insurance ($175), and a temporary liquor license ($10) to sell beer and wine to cover costs. The organization did shows featuring 20-40 artists (ranging from students to established professionals) in a parking garage, an old burned out ballroom, an empty building the art school owned, and even took over an entire floor of a high-rise office building.

While putting together exhibitions in these empty spaces was relatively inexpensive, they were often fairly labor-intensive shows. It took 7 hours just to run extension cords and hang clamp lights in the office building, and a few of MARN’s board members had to meet with the building’s management several times to assure them the artists would act “appropriately.”

While MARN was able to leverage its nonprofit status and board members’ connections in the business community to obtain spaces in the lean times following 9/11, as the economy continued to improve, finding free space for exhibitions became more and more difficult.

So in 2004, when I opened my gallery Hotcakes, MARN started using the space for all of the organization’s meetings, workshops, and annual exhibition that featured the artists in our mentoring program (many of whom are recent art school grads). Initially, my monthly expenses (fixed costs) at Hotcakes were about $1600, which included rent ($400), postcards ($230), stamps ($420), 4 cases of cheap wine ($144), food ($160), heat and electric ($120), phone ($90), insurance ($65), and my web server and email newsletter ($30). But after a couple years, I started doing all my promotion online, ditched my insurance, and had the gallery calls go to my mobile phone, which cut my expenses in half.

Luckily, after I closed Hotcakes and resigned as executive director of MARN in 2008, the annual mentor show’s proven track record, abundance of press, and high caliber of artists, made it easy for MARN to find another venue to continue the series.

While the economic crisis has been terrible for art sales the last couple years, it has made some really exciting exhibitions possible in Milwaukee. Just last week, three seniors from the University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, Makeal Flammini, Ella Dwyer, and Jes Myszka, put together an exhibit of over twenty local artists, poets, and musicians in and around a few of the empty buildings that used to house the Pabst brewery. Aside from art hung on walls, there were improvised performances, outdoor projections, and mud stencils on the old Pabst grain silos. The Parachute Project was formed specifically to hold shows in different vacant spaces each month. Makeal said they just made a list of realtors in the area and called each one until she found Mike Kleeber of Town Investments, who was excited by the idea of hosting local artists on Gallery Night. The one night event received a lot of great press, including on air interviews on two local radio stations, and cost the group just shy of $700, which included the $200 one-night event insurance policy.

For an event occurring the same night, MIAD professor, Jason Yi, found a great free venue to host an exhibition of his freshman students’ work, while sitting in his dentist’s chair. It turns out Jason’s dentist, Dr. Mike DeWan, loves art and saw a Gallery Night exhibit in the unrented, first floor of his building as a great opportunity to show off his space to potential tenants. Dr. DeWan even donated the $140 to print the postcards and paid for the food and drinks. The show cost MIAD and the students nothing. Jason was thrilled his students got a real experience organizing an exhibition (including writing press releases and designing postcards), and the feedback on the students’ work was fantastic.

Milwaukee’s next Gallery Night isn’t until July, but The Parachute Project has already met with the owner of their next exhibition space. Their recent success, as well as that of Jason’s students, will undoubtedly inspire other local artists to also create something interesting beyond the white box. I can’t wait to see what it is.

Pingback: Come Curious | Art21 Blog