During a recent visit to Exile Gallery, I spoke with guest curator Billy Miller about his concurrent shows Head Shop/Lost Horizon, which were a part of Exile’s annual Summer Camp Series. We chatted around a courtyard table, as a giant tarp made of discarded umbrellas loomed over us, engulfing the whole hof in cheap, translucent color and swaths of frayed paisley.

As Berlin’s erstwhile lover, the Sun, streamed through the fabric, the space flooded with light, a whimsical vision only slightly unhinged by party leftovers from one of the many events and screenings held in tandem with Head Shop/Lost Horizon.

While talking to Miller about consumerism and carelessness, he informed me that all the umbrellas had been gathered after a particularly rainy day in New York City by artist Justin Yockel, serving as spineless evidence of our slapdash culture. Like most of the work in Head Shop/Lost Horizon, Yockel deftly tongues around preachy or flippant tones in favor of more complicated language; a pretty impressive feat considering the topics of discussion include Facism, meth-making and Abu Ghraib.

According to Miller, Lost Horizon and Head Shop represent two different responses to a shrinking natural environment and an increasingly pervasive Beck-ish culture of fear. The difference in tenor between the rooms is immediately apparent. In Head-Shop, Miller sweetly eulogizes the head shops of the 60’s with a hyperactive installation of rambunctious political works, while Lost Horizon offers a quieter “frozen” view of loss.

In the latter, more subdued offering, visitors can make out the subtle mechanized groans of the doomed BP oil rig, a field recording Glynnis McDaris made shortly before the disaster. In contrast, the less sonorous but infinitely funnier Genesis P.Orridge dominates Head Shop, barking orders from a bunker cum basement while dressed as “Eva Adolf Braun Hitler.” While watching P.Orridge’s vaudevillian turn as a multi-gendered dictator, Miller praised the artists’ enduring “freakiness” and continued commitment to counterculture.

Speaking tenderly about the history of head shops in Detroit and his initiation into hippiedom, Miller claims that the stores sold more than just bobble-headed skeleton vaporizers, but rather traded in ideas and ideals unlikely to be found in the mainstream world, offering young deviants like himself an alternative creative business model and a safe space to be critical of corporate strategies.

He aptly likens the works in his own Head Shop to the relatively innocent consciousness-expanding drugs of the 60’s, while he claims that the pieces in Lost Horizon represent newer, more menacing concoctions like meth, crack, and heroin.

Some of the videos in Head Shop definitely read as “stoner art,” bearing the pulsating repetitive hallmarks of pyschedelia, including a love of fractals and dancing andro-tot Justin Bieber. One of the more mesmerizing is Justin Lowe’s video, which follows the lithe, noble movements of a killer whale as it sails through the water.

As an invocation of its namesake, it’s no surprise that Head Shop resembles a comic come to life, with store bought tchotchkes, newspaper-covered pedestals, and manic visuals. Two very graphic wallpaper installations encircle shiny collages by Assume Vivid Astro Focus and bubbly, penciled farm animals by Dan Acton. Mary Nicholson’s luscious drawings based on stills from French New Wave cinema exude the casual mischief and jarring sensuality of a Godard close-up.

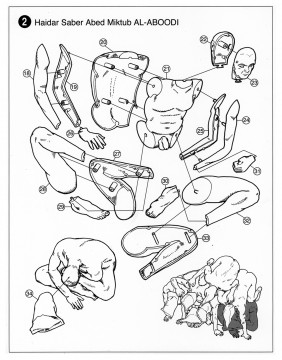

Noah Lyon (A.K.A. “Retard Riot“) creates a wallpaper design featuring another Führer-hybrid, this time as America’s favorite Burgermeister. Michael Magnan provides a detailed map for manufacturing meth and Lisa Kirk deconstructs the visual trappings of terror with a knitted ski-mask as a part of her project “Revolutionary Knitting Circle.” Equally tongue-in-cheek is Wayne Coe’s Human Pyramid Model, which consists of fully functional design plans for how to realize the infamous Abu Ghraib flesh tower as a plastic toy.

Where Head Shop playfully re-purposes our past, Lost Horizon alludes to a bleaker future. In the center of the room sits a cast resin rock, a sleek token of artist Peter Eide’s trip up a mountain. Like many of the other pieces on display, it feels like a mock artifact plucked from an ebbing landscape. Martin Gruendel offers shaped blue panels resembling shards of sky or “shattered perspective lines,” according to Miller. Equally haunting in their delicacy are Frank Webster’s watercolors of trees and other forested non-sites which, along with Colby Bird’s sagging faux-natural backdrop, resound with stillness. But perhaps most disarming is Jonah Groeneboer’s piece, which quietly hugs the corner and suggests a kind of topography that is both glassy and engineered.

Miller’s marked affection for, and extensive knowledge of all the works included, complements his curatorial philosophy that “if an artist does one good thing, that’s enough.” And like the overzealous keeper of a Wunderkammer, Miller values object over name, allowing works to commingle despite widely varying web presences and Artfacts rankings. Miller, a New York-based curator, editor, and independent publisher, will work with Exile again in the fall to present a large scale exhibition of lesser-known works by photographer/filmmaker Bob Mizer, founder of the Athletic Model Guild.