Why does art matter?

It’s a broad, reductive question – but one that has resounded with an almost vicious persistence since I moved back to Cairo, Egypt, last September.

Since the first days of the massive uprisings that began in this country exactly a year ago, there was an immediate turn to the visual to explain, celebrate, uphold, lead, or confound these sweeping social and political changes. Journalists, scholars, and curators set their sights on the arts as a key focal point in their efforts to turn this enormous, impossible to understand tide of events into a tidy, easy-to-circulate narrative. To that end, revolution-themed graffiti has been discussed ad nauseum; documentary films celebrating the allegedly newfound creative freedoms of post-Mubarak Egypt have been released at a rapid rate; and last spring saw an apotheosis of revolution-themed gallery shows in Egypt and abroad. Artists (and arts institutions) have alternately been panegyrized or criticized for their relative success or failure in transmitting the fervor of the uprisings.

So much has already been written about art and the Arab Spring, I am ambivalent (at best) about adding to the noise. Just like much of the art devoted to the revolution, the majority of the writing on this subject has ranged from the barely passable to the exasperating. In several instances, there is an uncritical, latently imperialist assumption that it is the arrival of Western-style democracy (which, it must be noted, has not in fact been implemented here) that has allowed for a sudden cultural renaissance. These narratives have clearly been crafted by those who haven’t done their research – critically robust cultural activity has been taking place in Egypt (and the broader region) since long before the fall of the Mubarak regime, and even long before the West first became interested in the region after 9/11.

Equally exasperating are those writers (and curators and filmmakers) who are insistently trying to instrumentalize the arts in this context, quixotically claiming that a body of artwork has the potential (or the obligation) to galvanize political consciousness, and lead the revolution. This tendency can be seen in this article that was published online in Al Jazeera English, or in this piece that was published in response.

The few voices of reason that stand out in the muddle, most notably Negar Azimi (editor-in-chief of Bidoun), sagely criticize the knee-jerk celebration of the cringe-worthy “revolutionary art” that has been produced since last January, insisting that artists from the region have been burdened with impossible expectations from an international audience. Kaelen Wilson-Goldie, the other must-read writer on arts in the region, adds to the complexity of the discussion by highlighting the problematics of the funding behind many of these revolution-themed exhibitions and projects, an issue that belies the alleged “freedom” some of these projects portend to express.

As a researcher/writer and arts administrator working in Cairo, for the past several months I’ve been trying to find a middle ground between these two discursive poles: the uncritical celebrations of the utopian idea of “free expression” in a post-Mubarak era, on the one end; and sober admonitions that the visual arts don’t, or can’t, have a responsibility towards the current political context, on the other. What is the importance of, or the potential for, art making in this current context? Why does art really matter as much as some of these articles and initiatives have claimed over the past year?

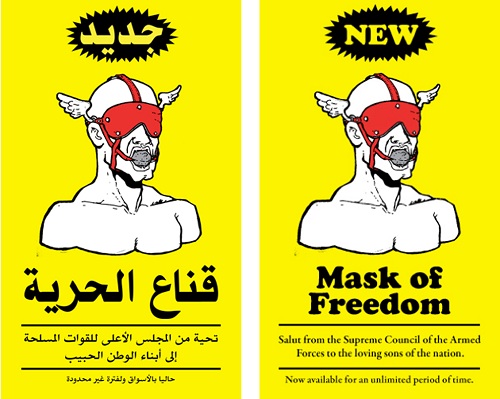

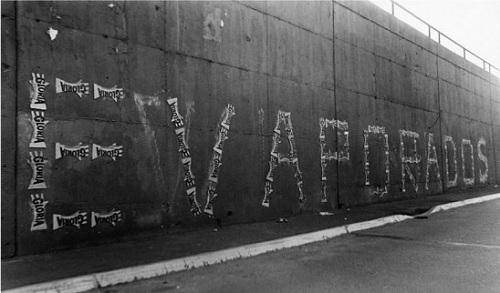

The political potential of art in times of conflict is a knotty issue that already has a vast bibliography, and these same questions have been explored in many other countries in crisis in the very near past. Artists’ responses to military dictatorships in Latin America, for instance, have proved a rich body of inquiry for art historians and curators. I think I have been expecting to encounter a Cairo equivalent of something like Artur Barrio’s Bundles – shocking, enigmatic interventions in public space in the midst of brutal oppression by the Brazilian military junta; or Peruvian artist Eduardo Villanes’ deeply moving Gloria Evaporada project, a series of related projects protesting the murder of political dissidents by dictator Alberto Fujimori’s government.

Artur Barrio. "Trouxas ensanguentadas, in Situação…T/T1; Belo Horizonte," April, 1970. From the book "Inverted Utopias. Avant-Garde Art in Latin America," p. 370.

But there hasn’t been this kind of raw, pointed, and very public artistic intervention in Cairo. Artists have responded in very different ways to the situation as compared to these earlier precedents. Some artists that I know have taken a hiatus from their practice, or have chosen to go abroad for months at a time on residencies to heal from the trauma of the violence and loss of life they experienced last January. Others have devoted themselves entirely to activism, often putting aside art making to take part in journalistic, documentary efforts. For instance, Lara Baladi, one of the more internationally recognized of Egypt’s contemporary artists, spent a good portion of 2011 focusing her energies on the Radio Ta7rir (a free, uncensored, online media platform) and Tahrir Cinema (an artist-organized initiative that involves projecting documentary footage from protests and clashes on a screen set up in Tahrir Square).

And those projects that have attempted to address the political head-on through artistic or curatorial platforms have been less than successful. Leaving aside the dozens of revolution-themed photography exhibitions and other “timely mediocrities” (as Azimi calls them), one example to consider is Bassem el Baroni’s book project 15 Ways to Leave Badiou – a measured, subtle, and thought-out response to the question of art’s role in a moment of political change. The book centers on Alain Badiou’s “15 theses for contemporary art,” a text that basically boils down to an obscure, hermetically-worded recipe for a form of contemporary art that would have the potential to overcome the evils of late capitalism. Baroni invited fifteen artists based in the region to respond to each of the theses, in a subtle gesture towards the political obligations and constraints that international audiences have been saddling these artists with since last January. But, as I’ve argued more extensively here, the book was too lofty in its aims, too pedantic, and too limited in its circulation to generate any kind of meaningful discussion; at least locally, it was functionally irrelevant.

Institutions have also been grappling with the question of the relevance of artistic practice in the context of current events. Over the past year, the Townhouse (the downtown non-profit art space where I’m based) has essentially discarded the curatorial program it had in place, instead opening its spaces for meetings, civil rights-oriented workshops, and experimental projects that don’t respond to current events so much as bring those events directly into the gallery space. “The Politics of Representation,” for instance, was an exhibition that ran through December and January, featuring a collection of posters and other ephemera produced by candidates running for Egypt’s first free parliamentary election, that were displayed in the gallery as an exercise in reading visual culture.

Curatorial discussions are now driven not only by questions of relevance, but especially of respect for the current situation. And the institution has continued to navigate a fine balance between providing a much-needed space for uncensored expression and discussion, and protecting both that space and our stakeholders from the potential backlash – a balancing act art spaces in Egypt, or the broader region, have always struggled with, but an act which has become even more precarious as of late.

The question of the importance, or relevance, of the arts (and my own position as an arts organizer) feels increasingly ponderous looking back at the events of the past year. Back in December, I was having coffee with a friend of mine downtown, just a few blocks away from deadly confrontations between protesters and soldiers in front of the Cabinet. He had recently returned to his art practice after an extended hibernation period, but was uncomfortable with it; making art felt selfish. Perhaps in the future the cultural expression from this period would be important for a more nuanced historical understanding of these events, he mused; but for now, it really didn’t matter. Art shouldn’t be high on the list of priorities in these times of crisis.

As I’m looking ahead at projects I’m planning in the coming months, and trying come up with potential solutions in case gallery programming is interrupted at the end of January and into February, I’m inclined to agree. Artistic production certainly has a larger importance for the shaping of cultural memory and historical narratives – in the future. But over the past few months, in a context where bullets and tear gas were dispersed merely meters away from gallery spaces, cultural work has inevitably been taxed with the anxiety of irrelevance. Time will tell if this continues to be the case as we look forward into what may become a second Arab Spring.

Pingback: Cairo in Context | One Year Later: The Myth of Art in the Arab Spring | Benjamin Phillips

Pingback: Cairo in Context | Alluring Archives: On Memory, Omission, and Research in an Unstable Region | Art21 Blog