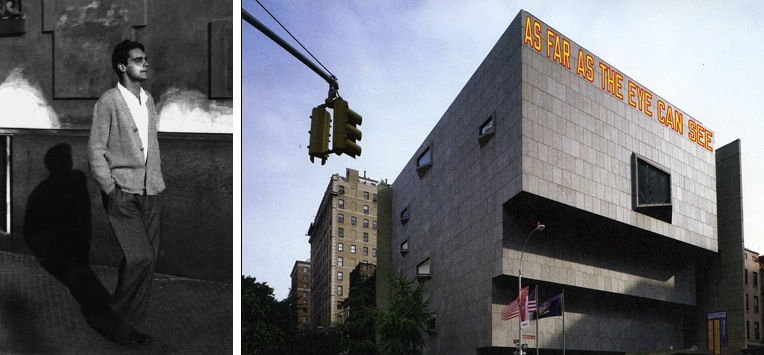

Left: Italo Calvino walking the invisible city of Turin. Image courtesy Gulio Einedi editors. Right: Lawrence Weiner's exterior installation for his "As Far As The Eye Can See" retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 2007. Image courtesy of Specific Object.

I don’t have to tell you, Art21 Blog Reader, how important words are to visual art and its makers. For the last few months artist and arts writer Meg Onli has unpacked for us the intricacies and unique qualities of art publications in her column Bound; frequent contributor Caroline Picard, who shines as one of the most interdisciplinary artists, authors and publishers in Chicago, thoughtfully references fiction every chance she gets; and in the last few weeks alone, guest bloggers like Dmitry Samarov, Lisa Anne Auerbach and Monica Westin have each expounded on the merits of text, language, storytelling, books and the general practice of composing with words in the name of visual art. Furthering such conversations, my stint as blogger-in-residence aims to show how words and images intrinsically relate to one another, both operating in a representative or narrative capacity and continuously fueling the semiotic fire. I would even go so far as to argue that they operate interchangeably—especially in visual art and literature.

In literary and art theory, there exists a term for this kind of relationship between images and words: intertextuality. Intertextuality unites, maybe even collapses, the realms of visual art and literature more than any conceptual device, and Italian author Italo Calvino may very well have been the master of its employment. Calvino’s post-modern novels charge the reader’s imagination with a complicated task of transforming words on the page into films on the screen into paintings on the wall into buildings on the street and back again to words on some other page not of a touchable reality, but in front of the face of a fictional reader. In nearly every work, the author composes complex networks of images and words that stand in for one another, creating a sort of hypertextuality that encompasses nearly every artistic discipline.

Calvino was so interested in the interchangeability of words and images that he presented a series of lectures dedicated to the matter at Harvard University titled, Six Memos for the Next Millennium. (There exist only five memos because Calvino passed away in the fall of 1985 just before he was to deliver the final lecture.) Similar to a draftsman’s set containing mark-making instruments of several hardnesses, shades and permanencies or a painter’s palette slathered with pigments of various opacities and luminosities, the chapters function as a set of tools—lightness, quickness, exactitude, visibility, and multiplicity—with which a writer can create a dynamic, clear picture without getting lost in the details. The chapter on visibility presents a lucid meditation on the importance of enabling vision through literature. Calvino’s treatment is brief but highly suggestive, showing that the visual image is subject to a remarkable amount of manipulation and aptly links the acts of reading and looking. His discussion of visual manipulation in literature ranges from Dante Alighieri and William Shakespeare to James Joyce and Luis Borges, and in much of his own fiction, he borrows and bends the already distorted depictions of time and space seen in paintings by Giorgio de Chirico, M.C. Escher, Paul Klee and more.

The importance Calvino places on vision—or how both the eye and the mind’s eye works—to experience text and image appears explicitly in his protagonists’ many demonstrations showing how the act of visual perception leads to deeper understanding. The fast-paced changes of narrative voice and setting in If on a winter’s night a traveler requires that the reader rely on the eyes of Reader One to guide them, while simultaneously maintaining their own sense of order in navigating the unorthodox patterns created by the text found on some of the novel’s overly designed pages. And in Cosmicomics’ “A Sign In Space” (my personal favorite by Calvino), the reader follows Qfwfq as he wings his way through the galaxies developing the universe’s first semiotics by marking and erasing all over the cosmos’ surfaces to outdo his nemesis, Kgwgk. Ironically, these characters have no form; they are but “a voice, a point of view, a human eye (or wink) projected into reality,” (Cosmicomics 7) yet their names, like a Kay Rosen piece, are meant to be seen rather than pronounced.

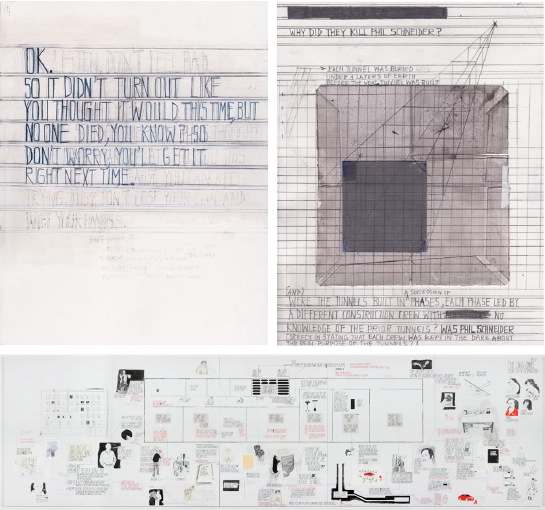

One can make incredible connections between these two stories and the tales/drawings of Deb Sokolow. Actually, I think Ms. Sokolow may have Calvino-reincarnate working as her studio assistant because if the author ever made a drawing, they would look and read like these. Sokolow’s remarkable (double-entendre intended) works almost always include a narrator traveling through a slightly disjointed space-time continuum of what may or may not be a paranoid delusion. This storyteller also remains formless as s/he takes the viewer on a tangled journey of words and images that have been marked, scratched out and erased into a beautifully designed visual composition.

Left: "Revision #7," 2011. Ink, graphite, acrylic on paper, 11" x 8 1/2. Right: "Why did they kill Phil Schneider?," 2011. Graphite, acrylic, collage on paper, 11 x 8 1/2 inches. Bottom: "You tell people that you're working really hard on things these days," 2010. Graphite, ink, acrylic, correction fluid, collage on 5 panels, 7 ft tall x 25 ft wide. Commissioned by and exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. All images courtesy Western Exhibitions.

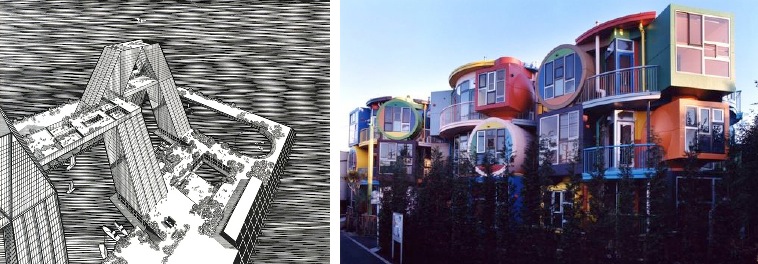

Perhaps Calvino’s most influential text for visual artists, Invisible Cities, whether explicitly or not, incorporates and continues to capture the visuals of artworks throughout time. The novel’s narrator, Marco Polo, moves swiftly between images and words via memory as he recounts the fantastic cities not appearing on Kublai Khan’s giant atlases in Invisible Cities. At times, the author even collates paintings by writing a parallel narrative that rids them of their stasis and gives them time-based movement as if they were each a film frame activated by the reeling projector. This appropriation and activation of modern painting comes to be an extremely fruitful strategy for Calvino, critically connecting his ideas on how to effectively establish visibility in writing to his favorite artists. Google Invisible Cities today and one can find innumerable artists’ works reconstructing Polo’s cities. I often imagine Julie Mehretu continuing Marco Polo’s illustrative journey, while Stanley Tigerman and the recently deceased Shusaku Arakawa, more Calvino’s contemporaries, seem to have drafted and built urban dreamscapes as if they were able to photograph Marco Polo’s mind’s eye view.

Left: Stanley Tigerman's "Kingdom of Atlantis," 2011. Ink on vellum. Image: Fnews Magazine. Right: Reversible Destiny Lofts in Tokyo designed by Shusaku Arakawa in collaboration with Madeline Gins in 2005.

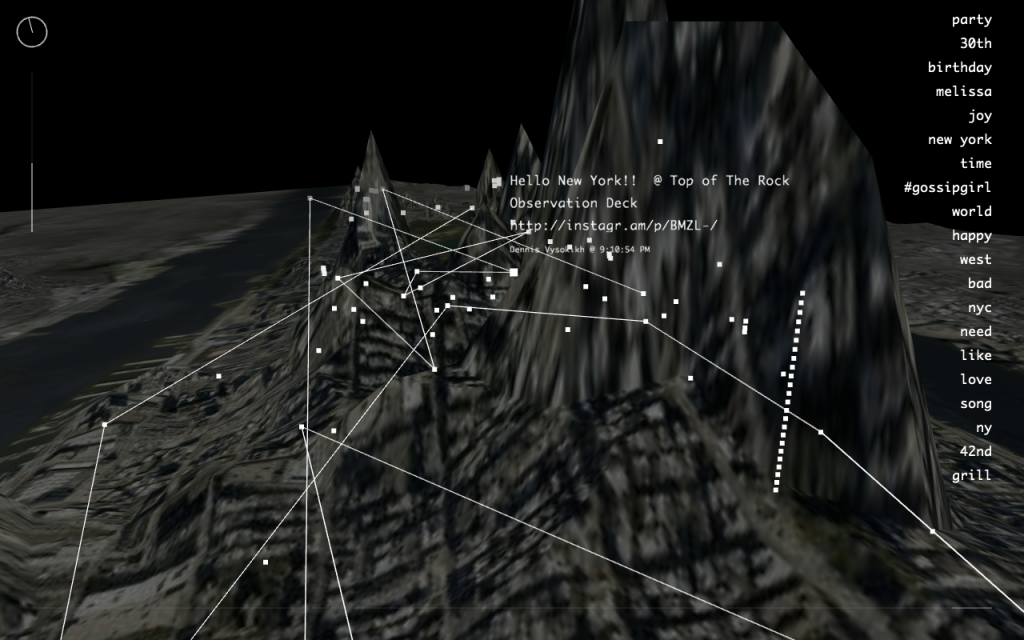

A self-professed science and technology fanatic, Calvino imagined a day when computers would make his writing come alive, continuous and organically regenerative, a feat he nearly accomplishes without the help of technology in the Invisible Cities novel. Unlike a film or a painting or music, Calvino worried that novels could not be repeatedly read fast enough to for the reader to experience them as a changing, time-based document. Quashing the author’s legitimate fears, Seattle-based artist and interactive designer Christian Marc Schmidt’s Invisible Cities art project makes Calvino’s dreams very much a reality. Because he describes his project with such precision, I give you Schmidt’s own words:

Invisible Cities aims to provide insight into the composition of urban social networks by surfacing data from online services, geographically mapped, in order to identify the areas of high and low activity. The visualization thus reveals emerging social themes, presented in a three-dimensional spatial environment. It displays individual Twitter status updates and Flickr photos on a geo-registered surface reflecting aggregate activity over time. As data records are accrued, the surface transforms into hills and valleys representing areas with high and low densities of data. Data points are connected in chronological order by paths representing themes extracted from status updates and image metadata.

In the novel version, Marco Polo uses his memory to build the cities and characterize their inhabitants. Eventually, the reader notices that every city is actually a mere fragment of Venice, the explorer’s hometown. At this realization, the book in its entirety suddenly becomes a travelogue of an interconnected world consisting only of Venetian metropolises to be surveyed and re-experienced by the great Venetian explorer. Similarly, Schmidt’s version collects New Yorkers’ written experiences and converts them to re-present the city to its dwellers.

Christian Marc Schmidt's "Invisible Cities," 2010. Screen shot 2011-01-24 at 9.17.04 PM. Image courtesy the artist.

Intertextuality, per Calvino’s and the aforementioned artists’ handling, proves magical yet tricky at times. Indeed, the reader/viewer must constantly reassess any given information and take some imaginative leaps to fully accomplish the interpretation process. However, at its best, intertextuality fuses together the visual arts and literature, all arts really, to exponentially broaden experience and by extension, understanding.

*Because one must give credit where credit is due, “Painting with Words, Writing with Pictures” originates as the title of literary critic Franco Ricci’s brilliant book exploring visual description and perception in Calvino’s stories.