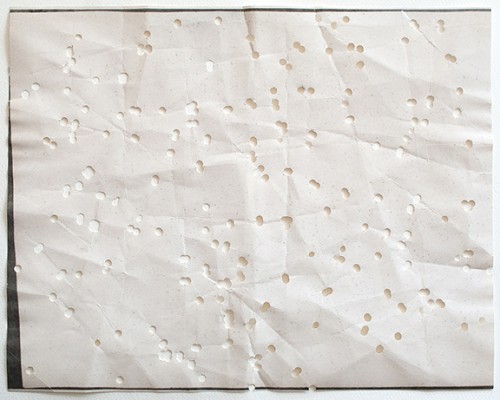

Aspen Mays. “Punched out stars 1,” 2011. Silver gelatin print, unique, 14.5 x 11.25 in. Courtesy the artist.

Aspen Mays traveled to Chile, the astronomy capital of the world, to look at the stars through some of the world’s most advanced telescopes. But over time, the bright stars, possible planets and meteors weren’t actually what interested Mays. Inside Chilean observatories, Mays discovered the stars of yesteryear—those that had already been discovered and documented, printed out on paper, and filed away in archival bins. Besides shifting the scope of her Fulbright fellowship (2009-2010), Mays’s experience changed her creative practice in other more jarring ways—she was affected by an extreme sense of isolation, and an earthquake that shook the country five days after she arrived.

Mays’s original plan was to go to Chile and make work about the experience of stargazing in observatories. But as she’s done with past bodies of work, such as Every Leaf on a Tree and From the Offices of Scientists, in which she acts as a cultural anthropologist studying specific structures, she left the project open-ended. For her, this type of approach yields the most productive results.

“In Chile, I thought I would do something like the Larry video,” she says.

Her 2008 work Larry is based on the possibly true story of “Lawnchair Larry,” an ordinary man who was determined to reach the stratosphere by attaching helium balloons to his lawn chair and simply sailing on up. He tried this experiment in 1982, traveling 16,000 feet above the Earth before his balloons popped and he tumbled back to the ground.

Mays worked with the 47th Annual AstroScience Workshop at Chicago’s Adler Planetarium to recreate Larry’s journey. She made a tiny Larry lawn chair replica, attached to it helium balloons, and sent it sailing sans human. The sculpture reached 96,000 feet before the balloons popped and it all came tumbling down. Mays attached a video camera to the piece, documenting its entire journey into endless blue.

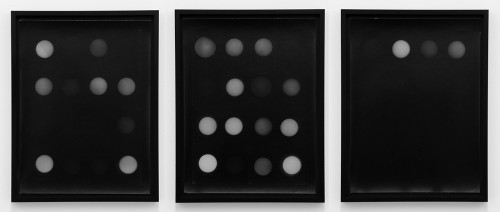

Mays left Chile with a new body of work entitled Sun Ruins, which she exhibited in the fall of 2011 at GOLDEN Gallery in New York. This body of work is comprised of two parts: First, Mays took some of the archival photographs from the Chilean astronomical observatory and in one series arranged 25 silver gelatin prints to show the sun’s progression in 1957. For the second part of the work, Mays punched holes in the photographs, rendering the stars invisible, and commenting on the ways in which stars move—faster than our fast-paced technology can document the fiery bodies.

Aspen Mays. “June” from the series “The Sun,” 1957. Each print 17 1/8 x 13 1/4 x 1 9/16 in, framed. Silver gelatin print. Courtesy the artist.

Although her Fulbright application revolved around the experience of Chile’s hi-tech telescopes, the work she produced is still very much in tune with her practice, which stands, as I wrote in a 2009 review for Art Papers, “in deft opposition to the technology we have come to rely on for answers, putting faith not in complex databases and rapidly evolving technology, but rather in the ability of everyday objects and materials to spark our imagination.”

Mays’s experience in Chile had a profound impact on her work. She learned to trust her own intuition completely, especially while in a place of personal isolation and natural disaster. But it was the possibility of destroying archival prints of celestial bodies that really sparked her Fulbright project.

“Getting to this moment of being willing and able to destroy the prints that are the punch-out star pieces [and] evaluating what you know about the Earth or anything—that experience opened my mind, not only about working with the archive but making it fragile, too,” says Mays. “Coming out of it now, two years later, and looking back, gave me a lot of confidence to really follow what I am interested in. Without such an extreme situation you don’t have to go all the way.”

Aspen Mays is now based in Los Angeles. She is currently Professor of Art at Ohio State University in Columbus. Her work has been featured in the New Yorker, New York Times, Artforum, and Art Papers.

Alicia Eler is Blogger-in-Residence through February 28.