The Zone is an ongoing research project that has different extensions; previously it has been shown as a multiscreen video and sound installation at the New Art Exchange and the 5th Jerusalem Show. Currently the artists are continuing the research for different forms of presentation, including a publication in collaboration with artist Raouf Haj Yahia and writer Nasser Abou-Rahme.

“We will be reborn anew”- FATAH poster 1984

Figures 1-2: Dystopic structures mark much of the contemporary Palestinian landscape. A walled tunnel connects two Palestinian towns and separates them from an Israeli bypass road above and in Ramallah a new advertisement is erected on a site of ruin. From The Tunnel Series & Desire and Disaster – The Zone 2011.

In what would appear to us as one of the darkest moments in Palestinian lived history, a ‘dream-world’ has somehow emerged in the West Bank: a host of commodified desires, semblance of normality, have been constructed atop the debris of political failure and collapse.

Here, new lifestyles, desires, senses of self mingle and collide with a persistent denial of the disasters of Palestine’s current situation.

Figure 3: A family marvels at the possibility of winning a model apartment through opening an account with a particular bank. From the series Desire and Disaster – The Zone 2011.

The Zone when presented as a multi-screen video and sound installation, evokes both the phantasmagoria of the dream-world and the dystopia of the catastrophe, reflecting this state of being which is full of surrealism, absurdity and a growing sense of the uncanny.

The research for the project explores the particular dynamics that have brought about the construction of a consumerist regime out of the remains of an aborted Palestinian struggle. In previous works we have looked at the failure of the Palestinian resistance movement, but for this project, we wanted to focus on what happened after the failure: the transformation of the PLO into an ‘authority’ and eventually a ‘security’ regime.

What struck us as most significant is the way in which this new regime displaced the old collective ‘dreams’ and gave birth to new political discourses and desires largely centered on consumption.

Figure 4: An old fading political mural juxtaposed against a new advertisement, the gesture mirrored and yet producing such narrative disjuncture. Whilst the mural symbolizes (of course reductively) the connection and rootedness in the land, the female in the ad for radio Sama appears floating in a white space the slogan above her reads “She has no boundaries’, both a reference to and negation of the occupation. From the series Desire and Disaster – The Zone 2011.

Through the phantasmagoria of new commercial developments, advertisements and a political rebranding of the Palestinian ‘leadership’, a particular dream-image situated in a kind of neo-liberal creed is being projected in the public spaces of West Bank cities.

Figures 4-6: Rebirths, New Palestinian subjects and signifiers, the successful business man, the bored housewife with money and time to spare, and the middle class nuclear family. To the right a billboard campaign for Mahmoud Abbas’s state bid in the UN, dressed in a suit and holding his fist up with a bunch of papers, the new image of the Palestinian leadership (as opposed to Yasser Arafat’s military fatigue’s and kuffiyeh clad with a rifle in one hand an the olive branch in the other) ironically the message reads “Palestine is reborn…this is my message”.

Figure 7: A plethora of new commercial developments are beginning to dominate parts of the Ramallah landscape.

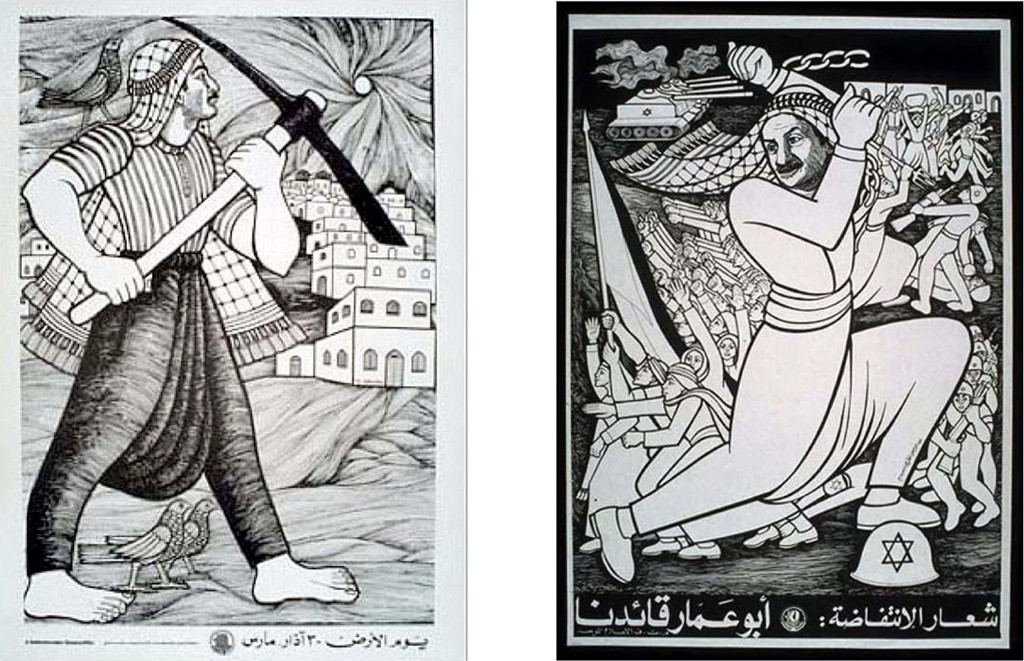

The images and discourses that had dominated the Palestinian landscape up until the after end of the Second Intifada- mostly political posters, graffiti or murals, have been for the most part systematically erased from the public space. Of course this not only raises questions about what is allowed or permitted to be displayed, but also how this visibility or its lack is shaping a radically different public imaginary at complete disjuncture with past narratives.

Figure 8: A billboard advertisement claims, “The Dream will come true”, except now it’s not clear what the dream is and even whose dream it is. Where previously public space was dominated by expressions of a collective dream of national liberation it is now replaced by an individuated consumer desire whose object of desire is constantly shifting. From the series Desire and Disaster – The Zone 2011.

Continued research took us to Nablus where we discovered that the old city, in a similar way to Palestinian refugee camps, is still very much publicly marked with old political posters of martyrs from the second intifada and a large amount of shrines and monuments to martyrs.

Figure 9-10: Shrines for martyrs in the old city of Nablus. From the series Desire and Disaster – The Zone 2011.

In fact, posters are being periodically reprinted and according to residents of the old city, there are plans to expand and improve these existing shrines. Interestingly, this space still carries a visible temporal disjuncture, a publicly played out tension between the old and the new dream, in this case, quite literally translated in the spatial division between the old and new city of Nablus. At the outer limits of the old city a meeting of these two moments happens, a temporal overlay.

Figures 11-13: New city meets old. Directly at one of the entrances to old city in Nablus a billboard with a poster honoring several martyrs from the Second Intifada surrounded by new commercial advertisements and stores, the island in the center has another martyrs shrine.

It is also here that we begin to witness a moment that is passing, a violent transition as it actively happens.

Yet it is not simply that the new is replacing the old, in some cases yes, but on many levels what we are seeing is the new permeated with the old. a hollowing out of the old dream/wish images rooted in a political reality (the dream of liberation that has marked the contemporary Palestinian experience for so long) and their rebirth in new ‘shells’, empty dream-images of a seemingly middle class utopia.

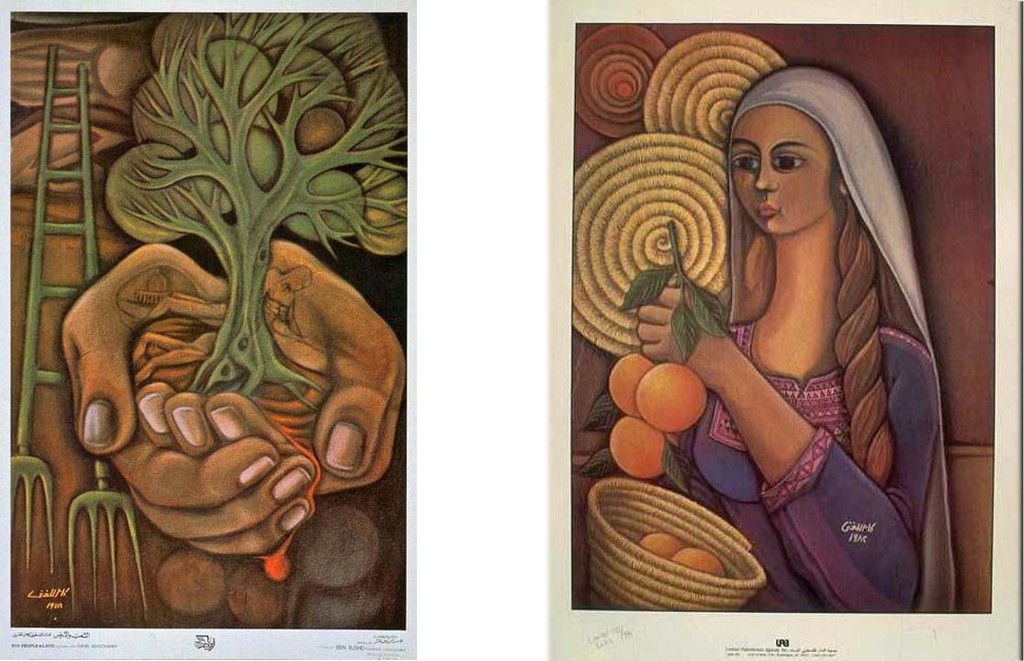

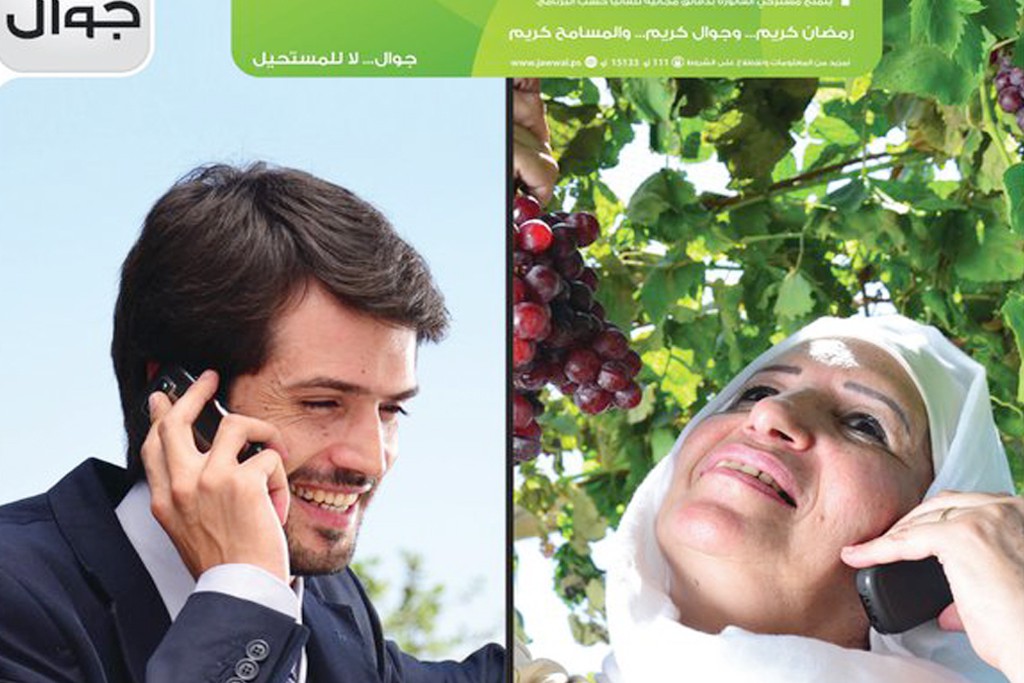

Figures 13-15: Advertisements and old political posters. When the PLO released its first posters the Palestinian farmer represented the quintessential symbolic figure of the` struggle for the homeland, here it appears again but to sell you a Jawwal mobile phone. As in previous examples the advertisement subtlety references complexities of the Palestinian situation by claiming “Your ambitions cannot be constrained, Say no to the impossible”, the solution being to buy Jawwal.

Many of the new advertisements appropriate a similar language and imagery to the PLO posters produced in the 60’s and 70’s, and in this way express a real utopian desire that is ultimately reified into a pure object.

New residential compounds multiply, whilst advertising billboards project images of consensual progress. The absurdities of this are clear when we just stop to consider that in order for us to invest in this new dream we must somehow ignore the increasingly visible violence of the colonial situation, this dreamworlds increasingly dystopian wider environment.

Figures 20-22: Dreams and nightmares. Above video still from The Zone, a figure stands amongst garbage and ruin looking out at a new Palestinian development disconcertingly resembling a settlement. Below, muted horizons, a series of new home devlopments have been named after Palestinian cities that residents of the West Bank are not allowed to enter without a permit, this one is Haifa Buildings, similarly an empty billboard on the Beir Zeit road with the distance to Jerusalem indicated. From the series Desire and Disaster – The Zone 2011.

But the violence, in its political and physical incarnations, cannot be ignored. It’s in the intensifying colonial structures, the ever evolving technologies of control and surveillance; walls; watchtowers; bypass tunnels… the spatial ‘rearrangements’ that are taking place at the imposed limits of Palestinian centers.

Figures 23-25: Technologies of control. A tunnel from which you emerge only to enter another walled tunnel and then yet another. This one connects the villages Al Jeeb and Bido but more importantly disconnects them from accessing the roads above, in this case bypass roads for the settlements of Givon and Har Shmuel. From the Tunnel Series-The Zone 2011.

It is here that dream becomes nightmare; this uncanny dialectic haunting a space at once filled with desire and disaster.

For two years from the balcony of our Ramallah apartment we documented an area in the centre of town rapidly developing, systematically old homes so quintessential of the place were torn down to make way for new commercial developments. Each video watched in isolation appears to depict a rather mundane, ordinary scene in a large town somewhere, but taken together begin to allude and enact a site of surveillance. Ultimately the scene is disturbed and put into question, is it just a growing town somewhere or are we in fact observing it from a watchtower?

The Zone was presented as an immersive environment, a site of ruin and dream, a physical reflection on a subjectivity marked by a double moment of colonial expansion/political defeat and impending statehood/consumptive regime.

Figures 26-28: The Zone installation view as presented in The New Art Exchange in Nottingham. The outer corridors were made up of 15 screens displaying different scenes from the balcony, intercepted by momentary disruptions, inside the two-screen installation.

In the narrow corridors and ominous room of The Zone the familiar feels strange, threatening, surveilled; at any given time one finds oneself navigating the dialectic of dreamworld and catastrophe, desire and disaster, past and present. The incongruence is arresting. The dissonance jarring.