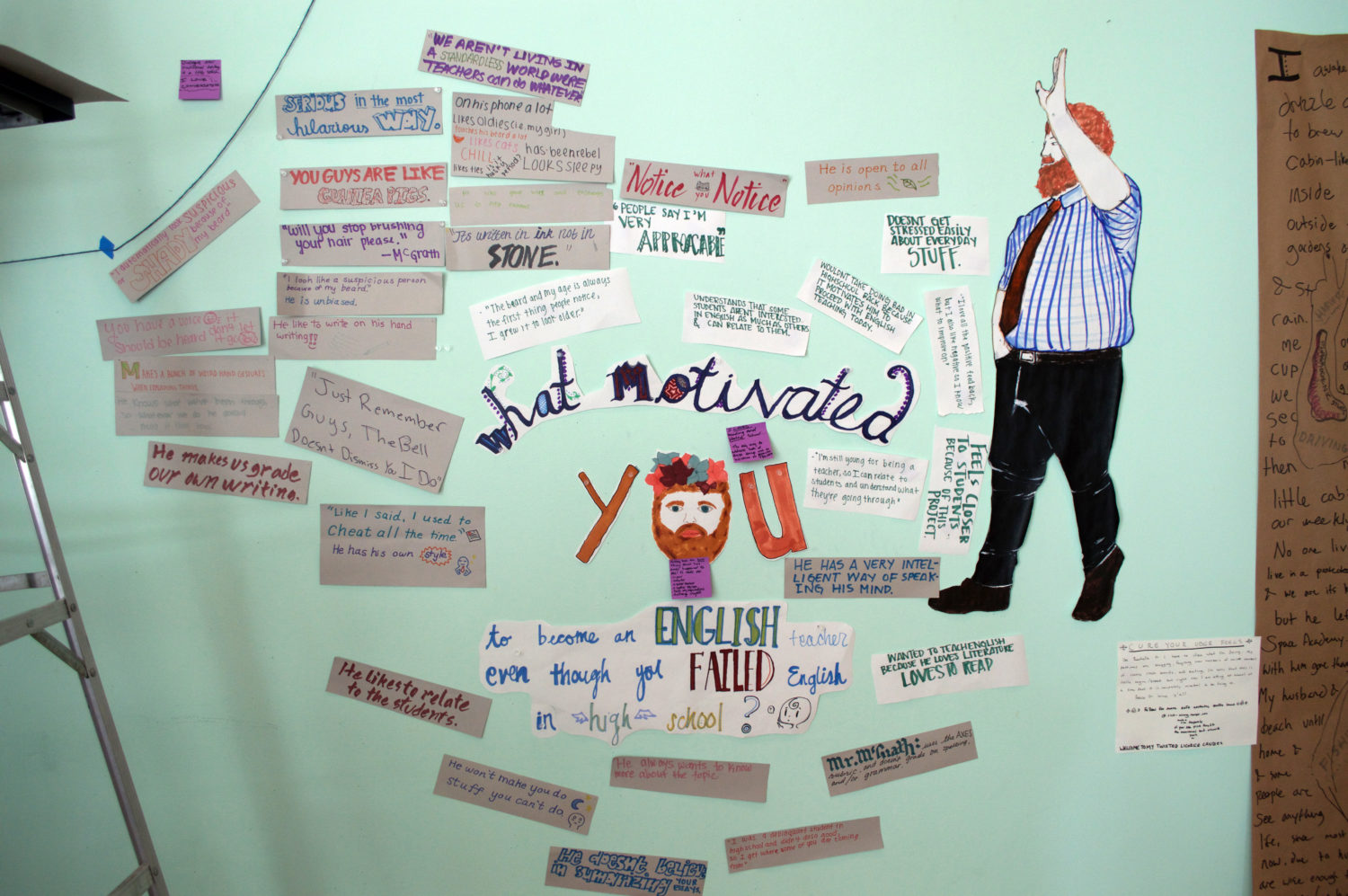

It is the first week of school at Washington High in Fremont, California. A group of tenth-grade students focuses, laser-like, on the words and body language of their English teacher as he paces the front of the room, extemporizing and leading a discussion about his rules and expectations for the coming school year. They take notes in accordion books they’d made in their art class. One student excitedly writes, “He said he failed English in high school!” Another student captures the teacher’s quote: “Don’t get married to your first idea.” Another observes, “His beard looks really soft.”

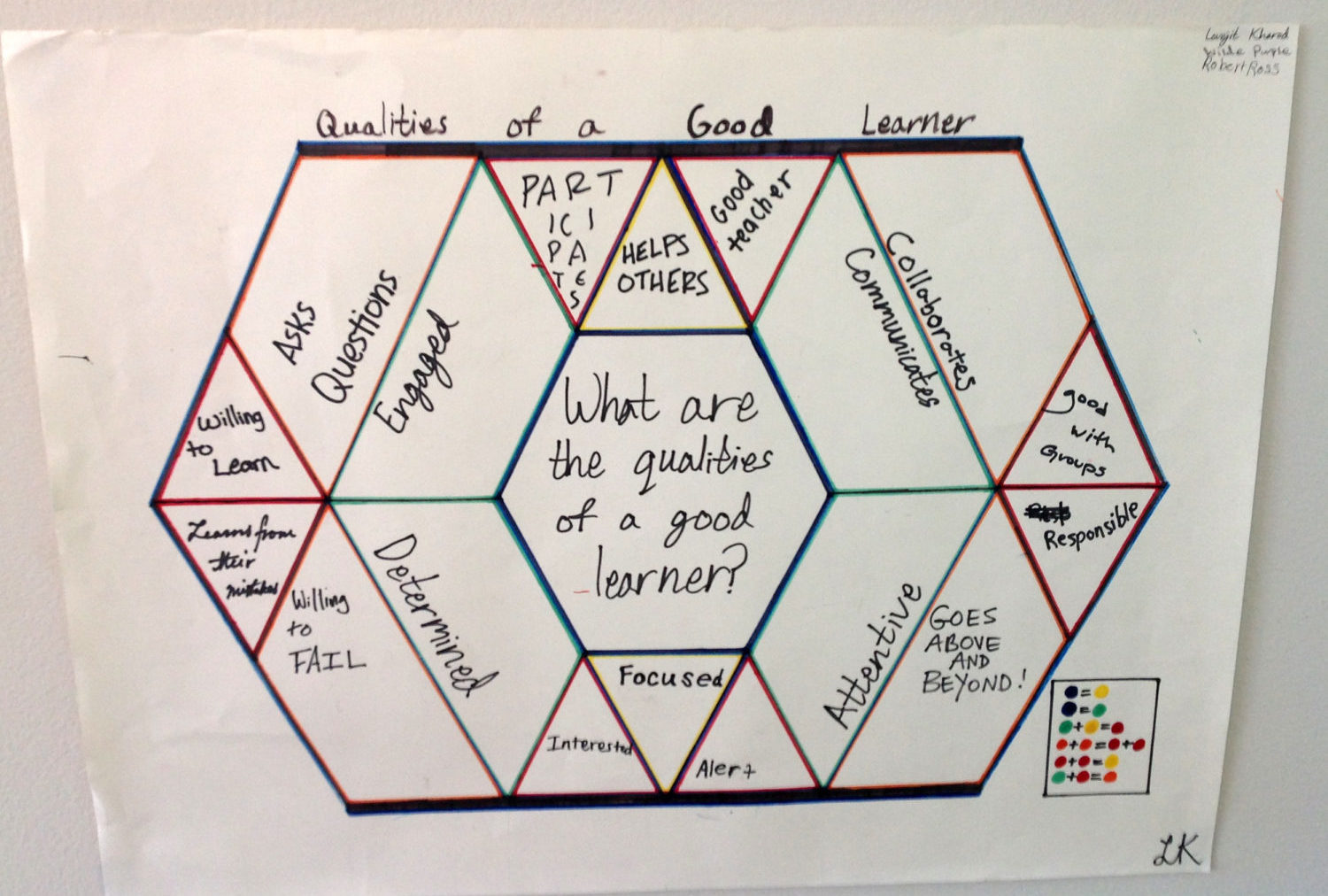

Later that day, in art class, the students compare notes and post their observations with pushpins on the back wall of the classroom, grouping them into categories such as “Objective Observations,” “Subjective Opinions,” and “Quotes.” The next day in art class, they collaboratively create colorful visual-concept maps, with topics like “Qualities of a Good Teacher” and “Qualities of a Bad Classroom.” In the following three weeks, the students develop research questions based on their daily observations of this English teacher, they design and create an evolving and interactive installation (at a Bay Area art museum) that illuminates their research, and they interview their teacher to gain further insight into his teaching philosophy. Meanwhile, this teacher has also been observing the students and developing his own research questions; the students and their teacher have conversations about their mutual findings. The museum installation concludes on a Saturday with a roundtable discussion about, among other things, the implications of upending typical power dynamics related to assessment in the classroom.

This was “Assessment as Dialogue,” a piece of experimental curriculum I conceived and co-created with my tenth-grade art students, who shared the same English teacher. It was inspired by the socially engaged contemporary-art practices of artists like Thomas Hirschhorn (as in his work, Gramsci Monument), Suzanne Lacy (such as her work, Three Weeks in January), and Oliver Herring (known for the open-ended participatory structures of TASK and Areas for Action) and was informed by strategies of qualitative discourse analysis and works by philosophers like Paulo Freire and Michel Foucault and practitioners of critical pedagogy like Jeff Duncan-Andrade and bell hooks. In the spirit of the videos made by Art21, below I will open a window onto the process and some of the catalysts that led to the creation of “Assessment as Dialogue.”

The first catalyst for the curriculum was Paulo Freire. In his book, Teachers as Cultural Workers, Freire discusses the traditional practice of teachers—“reading a class of students as though it were a text to be decoded”—and envisions classrooms where students reciprocate, “observing the gestures, language…and behavior of teachers.” Of course, students are already doing this, all the time; however, they are not typically invited in any structured way to share the results of these “readings” with their teachers or with each other. The power dynamic that Freire is uncovering here, the fact that assessment in almost all public-school classrooms travels in just one direction, from teacher to learner, was one of the major themes running through “Assessment as Dialogue.” For a long time, I’d wanted to redress this imbalance in my own classroom, and Freire’s words added urgency to that desire.

The next catalyst came when I saw a presentation by a group of art teachers at the annual National Art Educators Association conference, about an exhibition they had organized. In the exhibition, the teachers had drawn from and creatively reimagined the ephemera of their everyday classroom practices: handouts, directions on chalkboards, examples for art projects, and other physical manifestations of life in their art rooms. I loved that these objects, the evidence of the dailiness of teaching and learning, could be recontextualized and brought into an illuminating visual conversation in a gallery setting. Almost immediately, I had ideas: What if the students collected the ephemera from a particular teacher’s classroom? What if they gathered actual objects, like handouts, returned and marked-up work from the teacher, and other documentation of the teaching and learning going on in their class? And what if the exhibition’s goal was to “read”—to analyze and to assess—that particular teacher, in effect to flip the script on the assessment power dynamics, in at least one of their classes? And what if the analysis of all this evidence took place in art class? My small tsunami of ideas was followed closely by the realization that I did not want this experiment to simply be a mirror image of the one-sided manner in which assessment is usually practiced. I instead envisioned a space where the students and their teacher could share their observations and analyses with each other, and that ongoing conversations could inform a dialogue about what was working and what all members of this learning community might do to improve it, hence the title, “Assessment as Dialogue.”

A key piece of this experiment fell with great fortune into place: my students are I were invited by Bay Area artist Brett Cook, who works in socially engaged art, to participate in that year’s edition of Bay Area Now at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts (YBCA), in San Francisco, and to create artwork there about educational practice. We shared the YBCA gallery space with three other artist/educators—Mariah Rankine-Landers, Chinaka Hodge, and Evan Bissell—who created different yet complimentary installations that focused on other aspects of socially engaged, contemporary-art-informed education practices. Working with a very tight timeline, my students and I dove in to the project.

To begin, I proposed its basic premise to the students: If they were interested, they would be observing their English teacher and assessing him in a way that is different from how they were used to being assessed by their teachers. They told me they were very interested. I also mentioned that, in this process, they might be assuming a lot of different roles, sometimes simultaneously: at times they might be researchers, at other times artists, at other times teachers and students. I further set the stage by saying that this was going to be an art project but not in a way that they were familiar with. I asked them to research social-practice art, socially engaged art, relational art, site-specific art, and installation art and to collaboratively present slideshows to the class, sharing what they’d learned about these and other contemporary-art forms and methods. I asked them to think about and discuss the ways in which what we were doing with “Assessment as Dialogue” did or did not fit into those contemporary-art categories. I also revealed to the students that we were being given the giant opportunity to have all of their work exhibited in a gallery in a major Bay Area art museum.

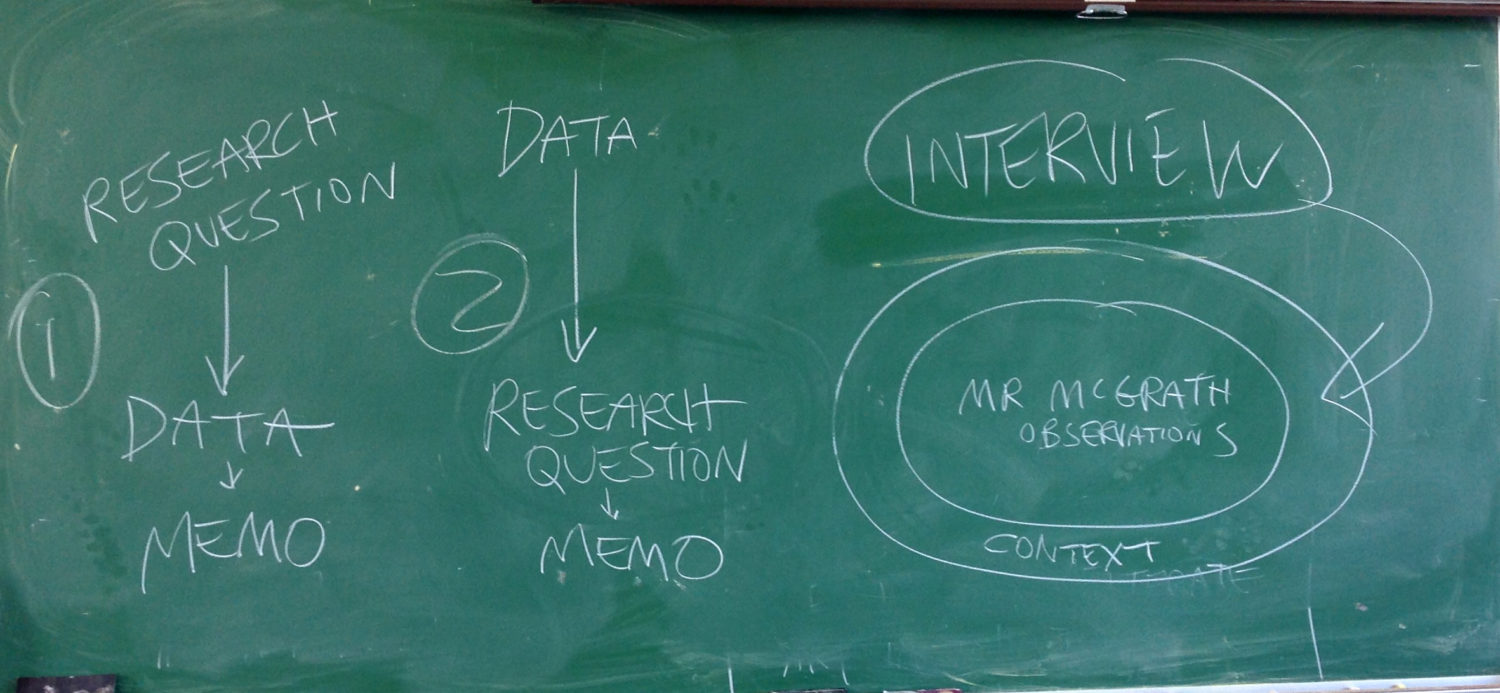

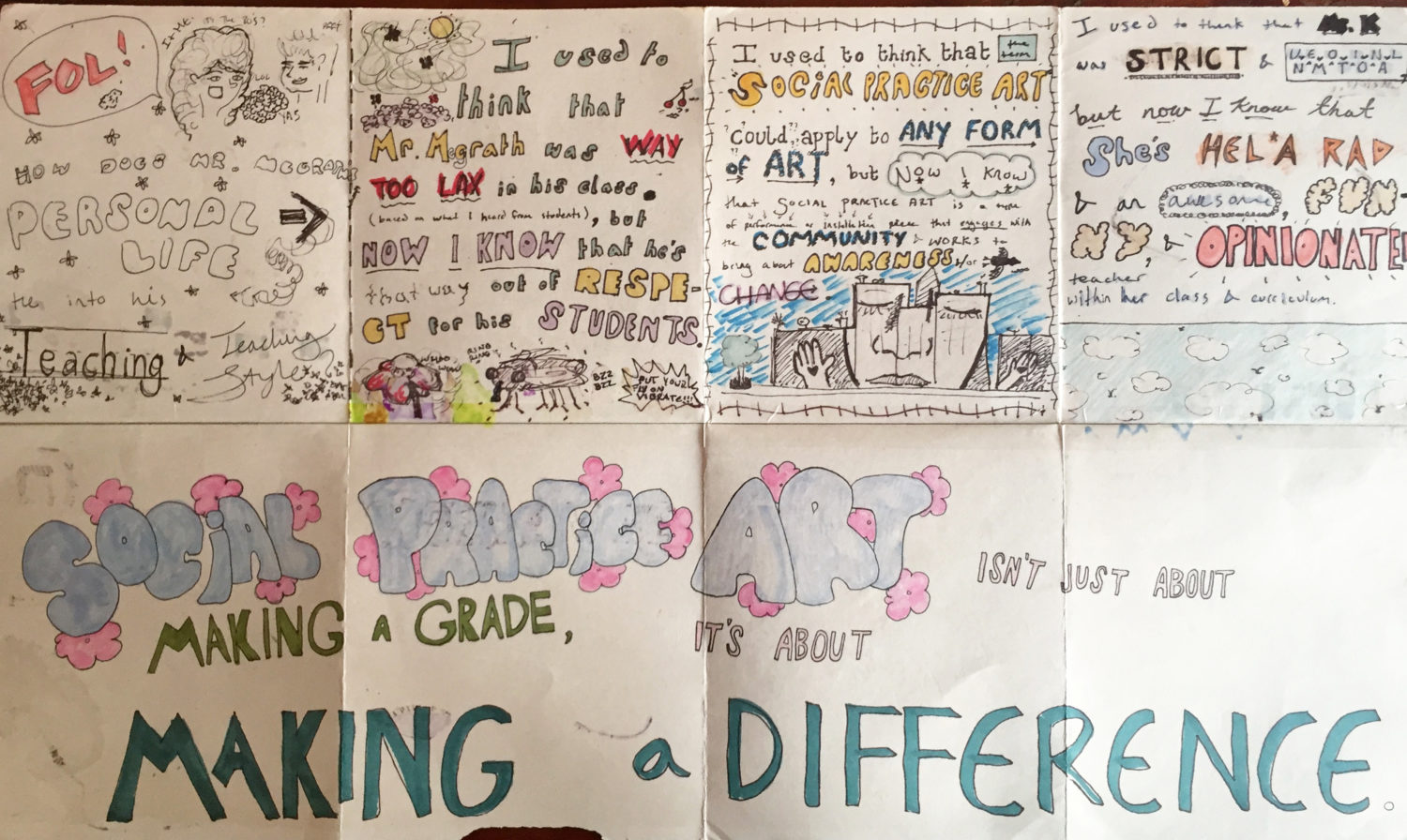

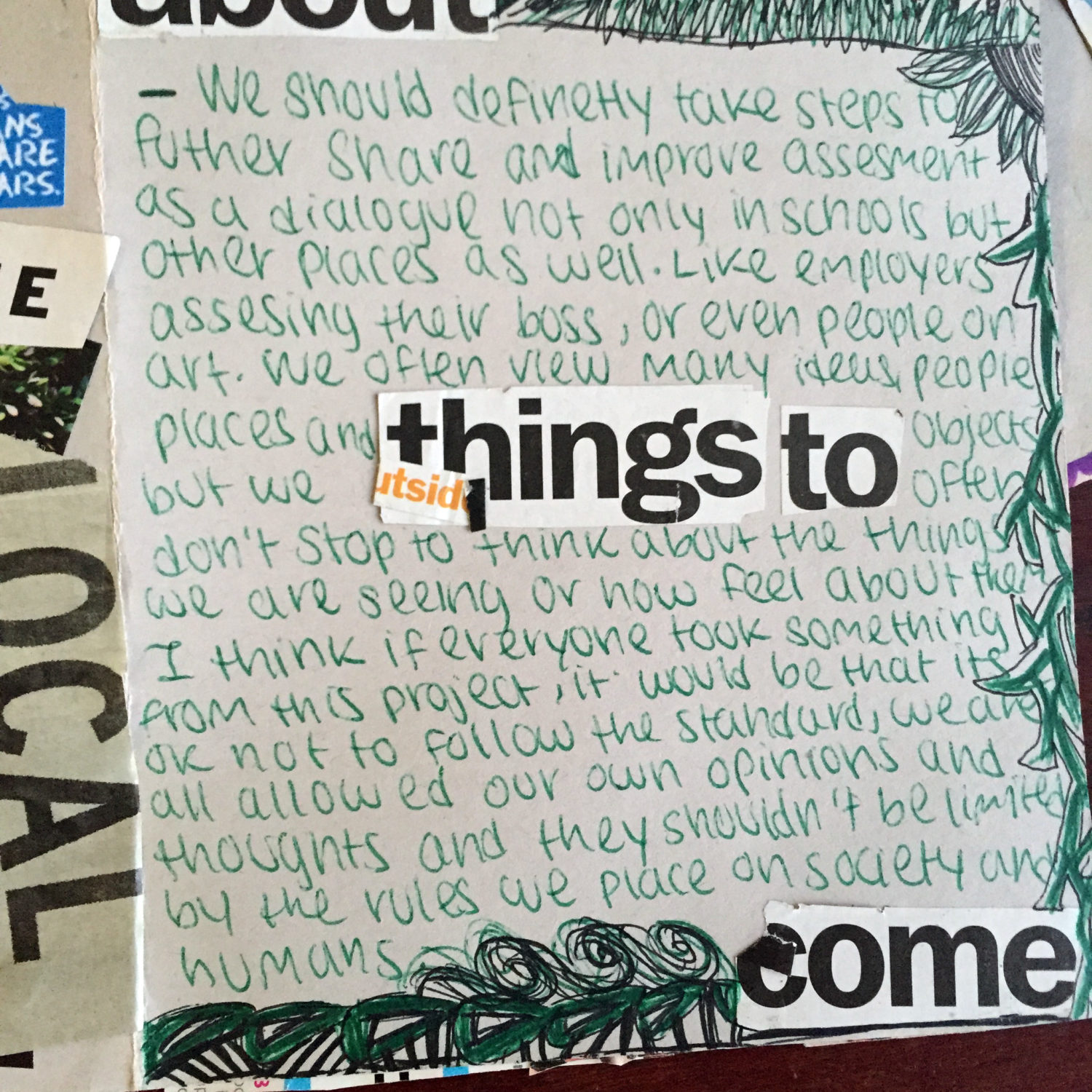

The next couple of weeks consisted of an intense flurry of activity: Students were observing, discussing observations, coding and analyzing data, inventing, curating, and focusing the visual and interactive elements of the project. The high-school art room became a planning and staging area for the exhibit, and the gallery space at YBCA became a satellite classroom, where we were constantly planning and implementing our next steps. The students twice reconfigured the contents of their exhibit at YBCA, reflecting the ongoing work and sometimes shifting directions of the project. Several other teachers helped to facilitate our work at the museum. Students came up with research questions based on the data they had collected and used those questions to drive conversations with their English teacher. For the final day of the exhibition, a multi-age community roundtable discussion in the gallery was promoted on social media, and it drew a large crowd of teens, educators, artists, and people who happened to be visiting the museum that Saturday. The strong turnout at the roundtable and the highly engaged participation made it an exciting and validating conclusion for all of us. The students’ summative work for “Assessment as Dialogue” was to create a graphic memo, a qualitative research tool I invented for the project, which consisted of a handmade accordion book filled with drawings, collages, free-writing, and responses to prompts I had given the students, to help them make visible their insights and what they had learned throughout the project.

In the end, I was reminded of the artist Thomas Hirschhorn’s words to the team who had created Gramsci Monument with him, “When you are creating an artwork, especially in a public space, it is never completely success, but what is nice is that it is never completely failure.” With our project, we couldn’t accomplish everything we wanted to. But what was important for me and for my students was that some important shifts had occurred in what we had all previously thought of as possible in the ways we think about teaching, learning, and assessment—and that contemporary-art practices had helped us get there.