Jocelyn Salaz is an artist and educator in Rio Rancho, New Mexico. She teaches art at Puesta del Sol Elementary School, and she has also worked with teenage witnesses of domestic violence at the non-profit Enlace Comunitario, which provides services to Spanish-speaking victims of domestic violence. She joined Art21 Educators in the program’s second year, and has remained an active member of the community ever since, presenting workshops at Summer Institutes and serving as a mentor for the program’s newest mentors. Dedicated to expanding access to the artistic process and teaching her students about underrepresented communities, Jocelyn joins us as the Educator-in-Residence for our upcoming Spring 2018 issue, “Rights of Passage.”

Art21: Why do you believe the thinking and practices of contemporary artists are important to incorporate in the classroom? What do students get out of it that they might not otherwise?

Jocelyn Salaz: In the current educational landscape of high stakes testing, compartmentalized subjects and rigid math and literacy schedules, students may see education as a means to a predetermined end. Even among elementary students I see frustration when first attempts do not result in the magnificent, pristine artwork that the students envisioned. But in a world where every aspect of our lives are interconnected, where there are competing values and complicated issues with no easy answers, I think students benefit from a problem-solving, process-oriented mindset that models persistence and inquiry.

It is important for students to see that there are multiple ways to address ideas and concepts. Curriculum models that focus only on the “look” of a work of art and seek to replicate an artist’s style, materials, or techniques without inquiry may produce pretty pictures. However, they do very little teach students about making mistakes, questioning, engaging concepts with materials, techniques and aesthetics, expressing ideas and opinions, and solving personal and communal problems. Contemporary artists serve as great models for this type of thinking as they reflect on their process, play with materials, and make mistakes. The multiple approaches of artists—particularly those in the Art21 videos I show my students—reveal a variety of ways to tackle an issue or skill, modeling the persistence students need to be problem-solvers and innovators.

Art21: Why were you initially drawn to the Art21 Educators program?

JS: I was initially drawn to Art21 after viewing the videos during art studio classes while I was working on my graduate degree in art education. Coming from an art history background, I was excited to see the work of contemporary artists dealing with contemporary issues as a model for my own budding studio and teaching practices. I specifically remember attending a screening of Alfredo Jaar’s Art in the Twenty-First Century segment at 516 Arts in Albuquerque, NM as part of their Speak Out: Art, Design & Politics exhibition programming. I was fascinated by Jaar’s conceptualization of images, their role in society and strategies for addressing real-world problems with images. Getting this peek into the thinking and processes of contemporary artists was incredibly inspiring to me as artist and educator. When I found the Facebook call for Art21 Educators, I saw it as an opportunity to explore how Art21 resources could help me more deeply explore contemporary art and practices with my own students, specifically young elementary students.

Art21: How has Art21 Educators changed your practice, as both an educator and an artist?

JS: Before attending my first Art21 Educators Summer Institute I would describe my curriculum as project-based. I would conceptualize a project, identify diverse artists working around a main theme or “Big Idea” and then plug in elements and principles of artworks, styles, materials, skills and techniques. While I liked to go deep with students and encouraged open-ended responses, there was still a strong emphasis on the end product.

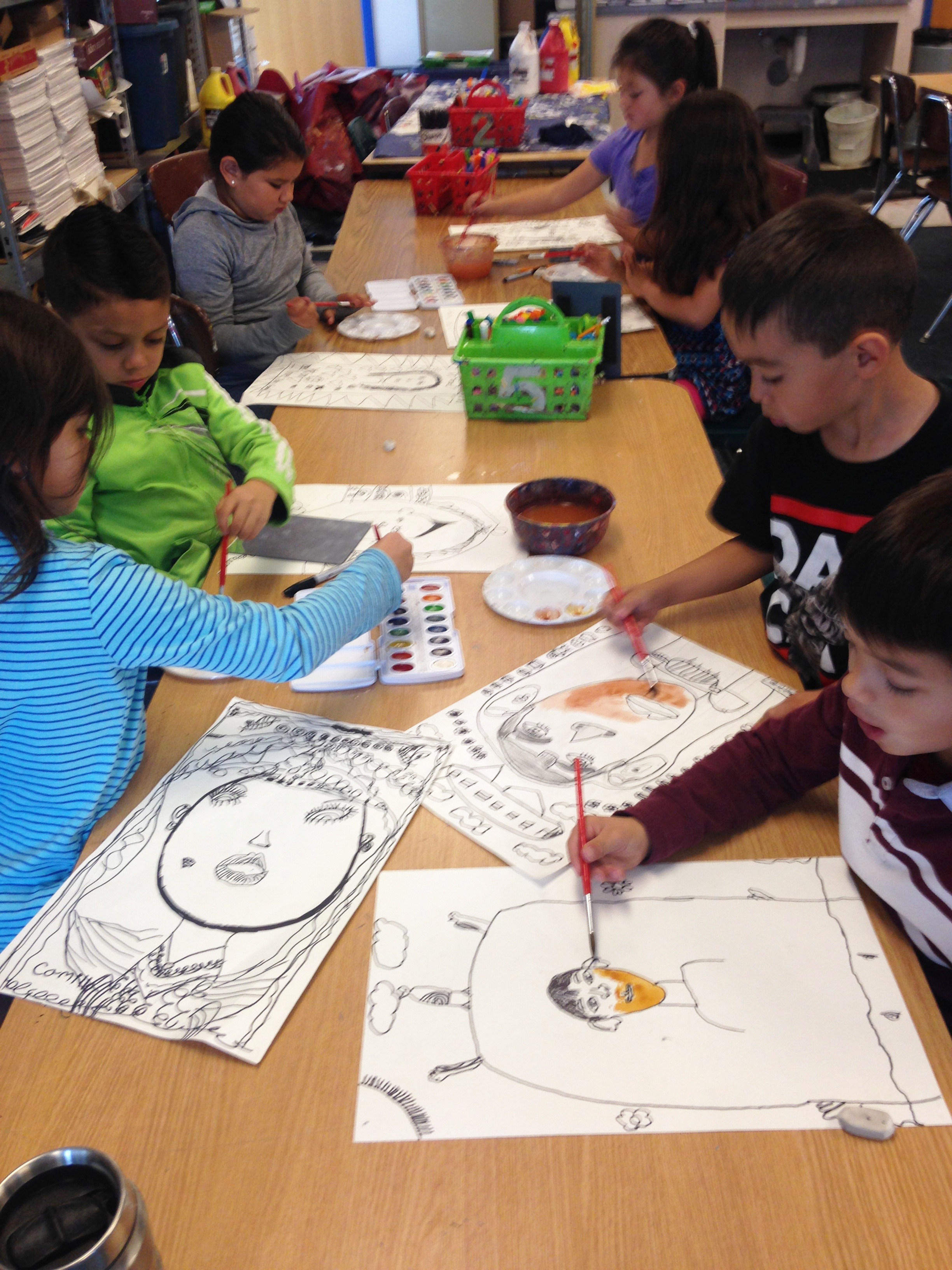

Art21 Educators shifted my curriculum from project-based with emphasis on the final piece to focus more on process. The unit of study that I produced during my initial year with Art21 Educators was centered around play as part of the creative process, based on my own memories of childhood and the magic that ensued when I was making toys and props. High school students were introduced to open-ended art play such as Oliver Herring’s TASK. We played with color, paint, collage and finally movement when students created moving puppet animations. Art21 videos of artists that specifically included play as part of their creative process, such as Oliver Herring, Jessica Stockholder, Gabriel Orozco, and Eleanor Antin, were shown to students to model play in the process of making art. While students experienced success and failures throughout the unit, the focus on process allowed them to be more forgiving of their failures and more thoughtful about what they were creating. This emphasis on process has since spread to my curriculum as a whole. While designing curriculum now, I ask myself what types of processes and strategies will guide students in understanding themes or concepts more deeply, in place of defining an end product.

Art21: How does your work as an educator relate to the upcoming Art21 Magazine issue, “Rights of Passage,” centered around the theme of access?

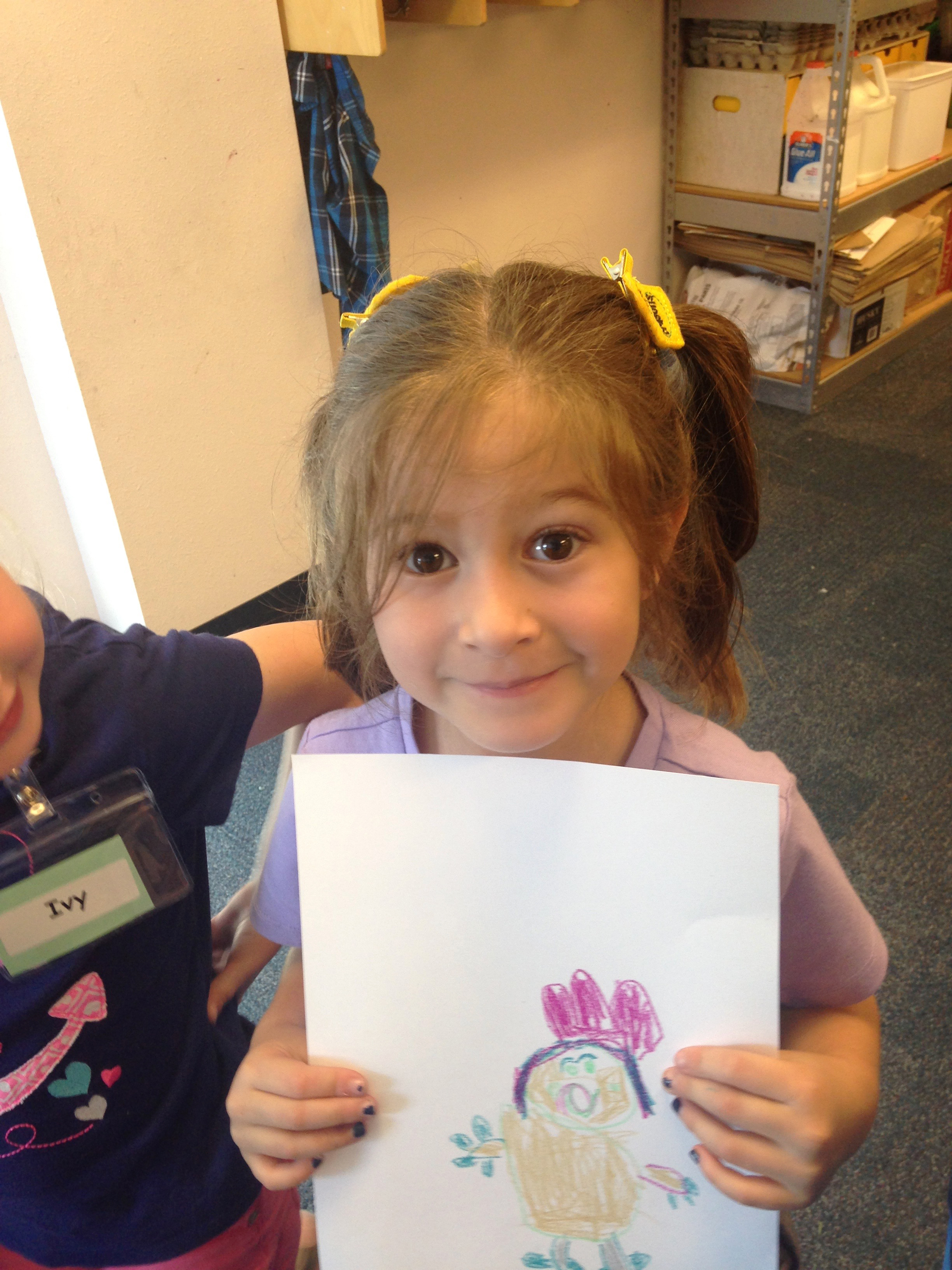

JS: Growing up in rural northern New Mexico, I was fortunate enough to have educators that gave me access to local history and knowledge of Chicano and Native American folklore, history, geography and art. My access to knowledge didn’t stop there, as my teachers connected me to the wider world of knowledge via books, technology, and field trips (In some cases to university laboratories to work on research for science fairs, which was a great interest of mine at the time). Having served mostly Latino and Native American students that are not widely acknowledged in popular American culture (or when acknowledged, in stereotypical ways), my goal as a teacher is to give students access to diverse artists that represent alternative aesthetics and groups of people whose perspectives and histories are not well-represented within the dominant culture. Grateful to my own teachers who ensured access to multiple bodies of knowledge, I let the following questions guide curriculum development and student inquiry in the arts:

- What stories are missing from history books and school curriculum and why?

- Whose images are missing from popular visual culture and why? How can we address this absence?

- What are the different aspects of my identity? What are the different ways I can reveal my identity that do not rely on the obvious?

- How can I transform my own world with what I have around me?

Art21: Describe a specific work of art, artist, or exhibition that has recently inspired you or your teaching practice.

JS: Last October I attended an educator’s night with a curator’s tour of the exhibition The Piñata Exhibit (Sure to be a Smash Hit!) at the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque. The show was curated by Tey Mariana Nunn, who explained that limited funding for exhibitions and a chance encounter with an early twentieth century piñata in a Santa Fe antique shop inspired her research into piñatas and the formation of the show. I was impressed with Nunn’s use of the Chicana “domesticana” aesthetic, “making the most from the least,” and how the show addressed time, history, materials, popular culture and political activism within the contemporary art world. For example, the show addresses the rise of “Trump” piñatas in Mexico and the United States as a response to the comments he made about Mexican immigrants during the 2016 presidential election.

Further articulating the concerns of the communities from which piñatas arise, it featured a piece of a miniature piñata border wall installation by Isaías Rodriguez, The Little Piñata Maker, which was a part of Estamos contra el muro / We are Against the Wall, a 2016 exhibition at the Southern Exposure Gallery in San Francisco. Rodriguez, the artist that led the workshop I attended, explained that creating a border wall with other artists that was later destroyed (as piñatas often are), was his way of addressing issues surrounding immigration in light of the current political landscape. Another contemporary work that utilizes the piñata aesthetic in a fresh way was Justin Favela’s El Madrid Lounge. Working with tissue paper, glue, and other piñata-affiliated materials, Favela creates large murals that address Latino aesthetics and identity. In an onsite installation produced during the exhibition, Favela chose to represent the murals on the façade of a local Albuquerque lounge in order to celebrate and elevate artists of color working in their own neighborhoods. Just as piñata makers respond in real time to the needs of their community, the piñata exhibit continued to add new piñatas made by local piñata artists until its closing. The show has encouraged me to look again and again at local traditions and aesthetics as inspiration both for art curriculum and for my own work.