Stephanie Syjuco. Chromakey Aftermath 1, 2017. Archival pigment print; 36 × 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York. Re-fabricated objects based on the physical residue found after public protests. © Stephanie Syjuco

This interview took place in Stephanie Syjuco’s East Oakland home on a gleaming June afternoon, squeezed into our busy schedules between flights and residencies, and accompanied by snacks culled from her garden. I first met Stephanie in 2008 in Pittsburgh, where we were both working at Carnegie Mellon University (she was a visiting assistant professor and I was the gallery director and curator). Years later, Ceci Moss and I included two of Stephanie’s projects in Alien She (2013–16), a traveling exhibition on the impact of the punk feminist movement Riot Grrrl on contemporary artists. —Astria Suparak

Astria Suparak: We’ve talked about how the 2016 election was a turning point in your understanding of your roles as an artist and as an educator. Can you tell me more about that revelation and where you are now, almost two years later?

Stephanie Syjuco: It goes without saying that the election shocked a lot of people, including artists who create work that reflects what’s in front of them—whether it’s a personal, emotional, or societal situation. Prior to the election, I was dealing with topics that were very broad: issues of globalization, copyright, or public access. While those can be specific in certain ways, they can also be so broad as to lack direct politics. And with the run-up to the election happening, I struggled with how to address politics more explicitly. I felt I didn’t have the luxury to be vague anymore. Things were unfolding in real time. After the election, I felt I had to shift my practice.

Astria Suparak: As an educator, you also felt a sharpening of your responsibilities during this time, right? Especially with what was going on in Berkeley, with the protests and counter-protests of white supremacist speakers on campus.

Stephanie Syjuco: Yes. I have a full-time job as a professor at UC Berkeley. A lot of that hinges on me being a professional artist, but I spend a lot of time working with students who, in some cases, are going through a new political reality, which could be in terms of how to navigate or negotiate what actions they are supposed to take as they look to the future. Many of them are immigrants, people of color, LGBTQ, young women, refugees, and even undocumented—people directly targeted by policies being put in place by the current administration. In my mentorship role, it became clear that I had to address the many emotional, confusing, and contradictory moments for them because it was manifesting in their work and in their lives. They are making artwork about their lives, and their lives are changing.

Astria Suparak: That’s a major responsibility to take on, especially with students at that critical age and juncture. Did you feel motivated, maybe earlier in your career, to push against stereotype—against what an “American” is supposed to look like, against what an Asian woman or an immigrant could be interested in or capable of making work about?

Stephanie Syjuco: While I think most of my projects don’t articulate a specific Asian identity, I think that people read that into the work, whether I like it or not. People have assumptions of what kind of work I should be making.

I am adamant, especially in this political climate, that my work be considered American. Of course, it literally is American, by virtue of me having grown up in the United States and being culturally American. But I think it’s important now to claim that, specifically for Asian Americans, because the political climate is creating polarizing spheres of who is and who isn’t seen as truly American. Asians are constantly seen as outsiders, of not belonging here. I want to strongly stake the claim that I am an American artist as much as an Asian American one.

Astria Suparak: I am in complete alignment with all of that. I’ve heard Black and Brown colleagues talk about the self-imposed pressure to mentor because they know young people of color have few role models, few professors and artists who look like them and can talk about experiences and issues that may resonate more closely with their lives.

Stephanie Syjuco: When CITIZENS opened at Ryan Lee Gallery in New York, a group of graduate students who were predominantly young artists of color visited. They were really curious to talk about it because it was one of the first times that they’d seen someone who looked like me making work that appeared so overtly political, and I think they were considering it as a possibility for themselves. My show featured photographs of people of color representing political resistors. The students saw themselves reflected in a way that they hadn’t seen in other art works.

Stephanie Syjuco. CITIZEN (Portrait of P), 2017. A series of fictional portraits of anti-fascist activists, developed with and modeled by students who witnessed campus protests. Archival pigment inkjet; 40 × 30 inches. Courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York. © Stephanie Syjuco.

Astria Suparak: During our lifetimes, there has been an evergreen critique of art that’s considered too political, too didactic. Or, more recently, not political enough, like it’s ineffective existing within an art institution. Or not political in the right way.

I recall seeing on Facebook someone’s criticism of your CITIZENS exhibition because it contained symbols and aesthetics from real, specific protests, which that person felt was inappropriate for an artist to use in a gallery setting, especially a commercial one. How are you feeling today about political art within a white cube and about those persistent complaints?

Stephanie Syjuco: It’s tricky. You and I are in the same generation and came of age in the 1990s. I remember going to school as a young art student and being heavily influenced by identity politics. Now, thirty years later, that cultural work has taken on a different, negative spin in some circles. It’s also seen differently by a younger generation. I learned a lot from those early years in art school and from the 1993 Whitney Biennial, the pivotal one that not only polarized a lot of people but also brought a lot of artwork into the forefront. It made a big impression on me, but so did the backlash against it. Broader cultural representation was finally happening in contemporary art, and these strident voices were able to speak out. But the criticisms lobbed against them were: “This isn’t good art,” “It’s art for a specific cause, and it isn’t relatable to everybody’s lives,” or “It’s sacrificing aesthetics for politics.”

After creating my most recent exhibition, in which I explicitly dealt with some of the protest imagery that I was witnessing, a different dialogue came up: Should these images be in the art world and the commercial gallery, or do they belong in the street—not because political art doesn’t belong in the gallery but because the gallery is a tainted, commercial, and out-of-context site for activist work that is happening right now? In other words, by making work about real protests, was I wrongfully capitalizing from political imagery in a way that I shouldn’t be?

I hoped that the exhibition put a spotlight on post-election issues, in a way that I hadn’t yet seen artists do. I was pulling from direct observation, as a witness to the protests, and I wanted to reflect on what I saw.

Stephanie Syjuco. Ungovernable (Hoist) (left) and Ungovernable (Fold) (right). Installation view of the exhibition “Stephanie Syjuco: CITIZENS” at RYAN LEE, New York, 2017. Sewn muslin and steel armatures; dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York. © Stephanie Syjuco.

Astria Suparak: I think that’s an important distinction: you were physically on the ground, actively participating in the protests.

Stephanie Syjuco: Exactly. I wouldn’t define myself as an activist, and that’s not to make a big distinction between art and activism. I think being an activist is actually a job that’s much more important than what I am doing as an artist. But I do feel like I create work that has an activist nature and that supports activist causes. Something I don’t make explicit in some of these projects is that I donate my sales to nonprofit advocacy groups. It doesn’t make sense for me to profit from certain works, given the subject matter.

Astria Suparak: The photo series reflected the present, but your work often connects to histories, archives, and “unruly materials,” as you describe them.

Stephanie Syjuco: I’ve been thinking a lot about how exhibitions function as visual archives. An exhibition is a space where, whatever is happening in the studio, the work has to pause and be presented in a way that the public is able to understand and see the narrative arc. Back to the CITIZENS show: I needed to act as a documenter to what I saw, to what other people saw during those moments of tumult.

At multiple times during 2017, protests erupted on the Berkeley campus, in which political forces were playing out. The protests were incredibly dramatic and very scary, in some cases. With others in my campus community, I was trying to process these events. By creating work about them, I was locking into my experience and attempting to freeze an external picture of what I saw.

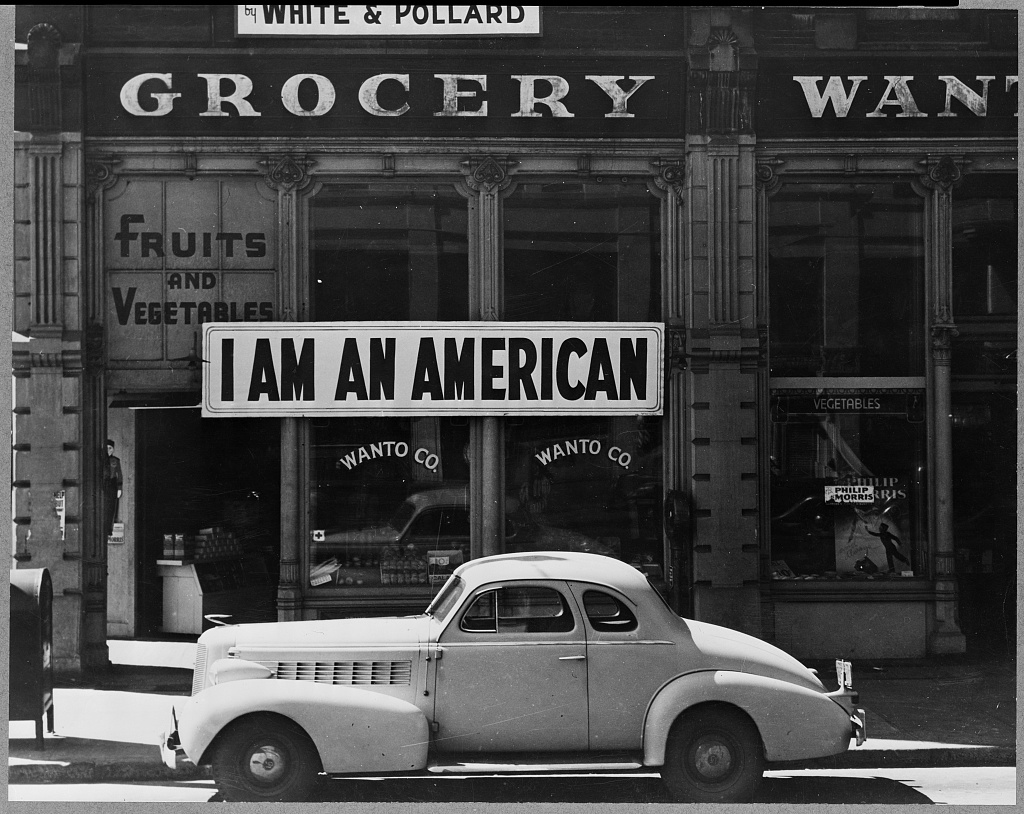

Astria Suparak: You were also correlating different historical moments in the show, like with your banner that references the “I Am An American” sign put up by the shopkeeper Tatsuro Matsuda during the internment of [more than 100,000] Japanese Americans during World War II.

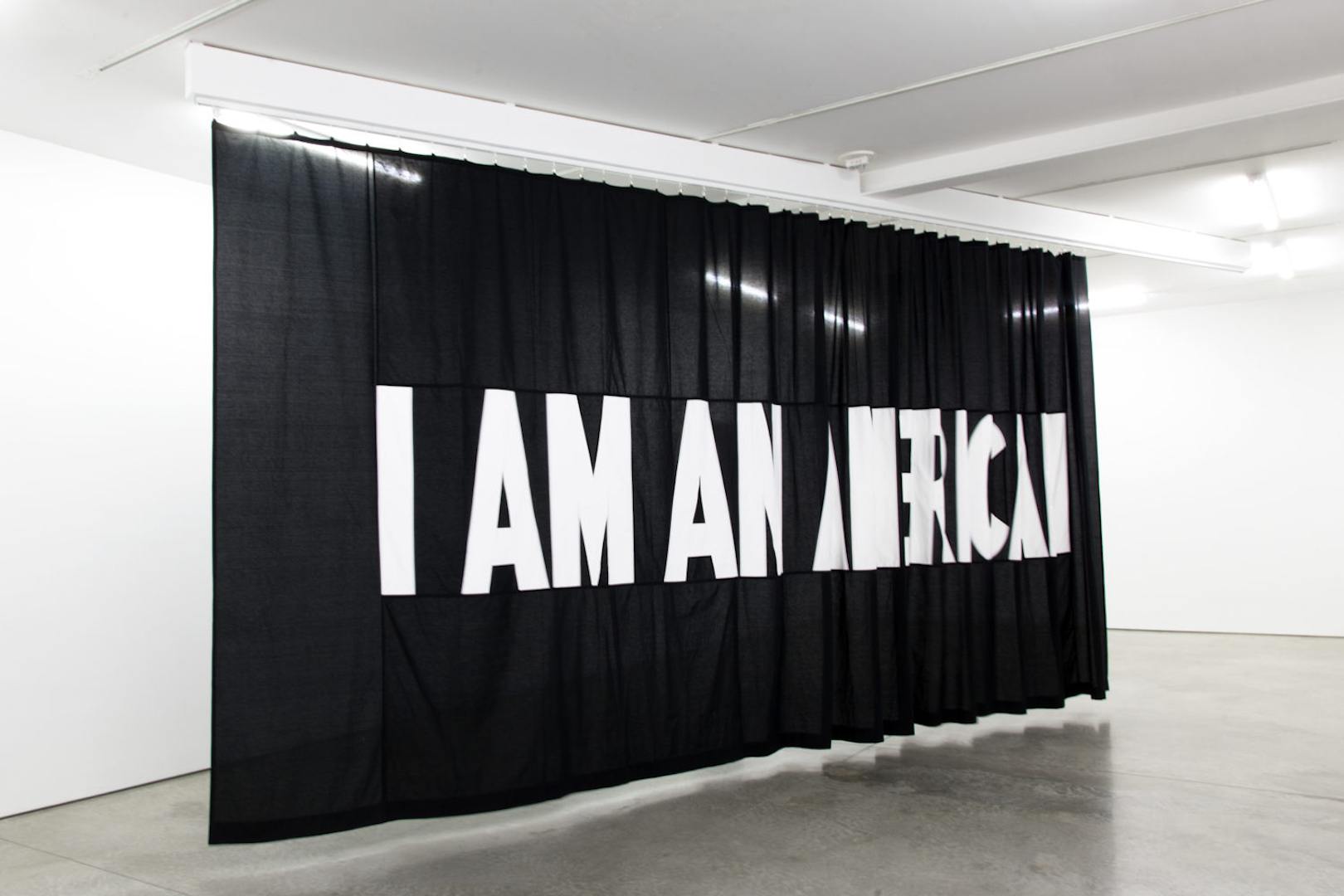

Stephanie Syjuco. I Am An… Installation view of the exhibition “Stephanie Syjuco: CITIZENS” at RYAN LEE, New York, 2017. An inverted copy of a sign posted by a Japanese American business owner in Oakland, California following the bombing of Pearl Harbor; the original photograph was taken by Dorothea Lange, and the shopkeeper was subsequently taken to an internment camp despite his plea of citizenship. Sewn cotton panel on moveable ceiling track; 9 × 24 feet. Courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York. © Stephanie Syjuco.

Oakland, Calif., Mar. 1942. A large sign reading “I am an American” placed in the window of a store, at [401 – 403 Eighth] and Franklin streets, on December 8, the day after Pearl Harbor. The store was closed following orders to persons of Japanese descent to evacuate from certain West Coast areas. The owner, a University of California graduate, will be housed with hundreds of evacuees in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration of the war. Photograph by Dorothea Lange, 1942.

I struggle over negotiating the functional divide between art and activism and how these worlds do and don’t meet. I know that other artists and curators also think about this a lot. For instance, we can go into a museum today and view exhibitions of political posters from the 1960s and later. These are objects that were created to function in the world, and they have entered a visual archive as artifacts. But they also function as contemporary touchstones to help us realize that we have been in this situation before. I’ve been thinking a lot about the oddness of the functional sign, the protest accessory—or protest prop—and how it can go back and forth between being a historical art object and something that had nothing to do with the art world when it was made. Many of these things were made by artists but went out into the world because they had to do something.

I made the CITIZENS show specifically for a commercial gallery space in New York. The signs in that show were not the protest signs that I was concurrently making for the street, for my project, Reap What You Sew. I see these projects as two separate things. For the gallery exhibition, I made a set of objects that attempted to critically examine how protest signs are distorted, manipulated, and sometimes rendered illegible by the media. Meanwhile, my public-protest signs are straightforward and functional in their messaging; they are a different type of speech.

Artist Alex Hernandez works the embroidery machine to produce patches and text-based panels during Stephanie Syjuco’s “Reap What You Sew” workshop in January 2017. Courtesy of the artist.

Astria Suparak: You’re an artist who works on several levels: formal and political, conceptual and practical. Your work also critiques and comments upon popular culture, technology, art history, and various movements and cultures.

Stephanie Syjuco: Hopefully all of us can do that! I am a citizen—and I mean that in the civic sense, of being an active civic participant in society—and an artist, and at times those two things diverge. I am often asked by young artists, “Is what we do as artists really what we need right now, in this political moment?” I used to say, “Yes, just keep making your work; that itself is a political act.” But in the past year and a half, I realized that although making art can be a reflection of our time, it isn’t the most expedient way to create a political effect. Sometimes you have to participate in direct action, as opposed to making art about politics. I think one needs to act as a citizen at the appropriate moment, not just be an artist in the studio.

Astria Suparak: There’s speed and responsiveness, and there’s context.

Stephanie Syjuco: When I’m making art, I hope that it will enter into a larger art-historical dialogue. Maybe, if I’m lucky, decades from now, it will be carried forward to say, “This happened before. Here’s the visual evidence of it in our art world, in art history.” This is in contrast to the protest signs, props, or other things that I’ve put into the world that will most likely be forgotten. I haven’t been keeping them; I’m not saving them in a flat file to donate to a museum later. They’re lost, or I lend them out. I’m less hopeful that they will circulate beyond that moment, and they don’t need to. They have their own context, and they did their work.

Astria Suparak: I’ve heard you distinguish between paper signs and fabric banners. Some protest signs need to be made quickly, for an immediate response to an urgent moment. But protest signs can also be made to be durable and reusable.

Stephanie Syjuco: Yes, the difference between permanence and impermanence makes me think about some of the concerns you faced in your curatorial projects, specifically the zine archive you created for Alien She. The cheap, low-budget zines weren’t originally meant to be in a museum. Who knows if some of the zine makers would be flattered by being included in a museum show or would have thought that it was an inappropriate context for their work. But for the sake of historical knowledge, the zines need to be circulated in the public imagination.

Astria Suparak: When Ceci Moss and I were putting the exhibition together, which included a section focused on you, with some of your projects that invite the visitor to become producers and distributors of the work, Riot Grrrl had been flattened and misremembered as a briefly lived subgenre of music. We were trying to present Riot Grrrl as a creative, activist movement that had a long-lasting impact, including on the lives of present-day artists like yourself.

The Counterfeit Crochet Project (Critique of a Political Economy) and FREE TEXTS: An Open Source Reading Room by Stephanie Syjuco in Alien She at Vox Populi, Philadelphia, March 7 – April 27, 2014.

The zines we exhibited were from personal and institutional collections, but we also reached out directly to many of the zinesters and musicians to obtain permissions or to invite them to contribute. Many of them visited the show, and we saw a lot of happy, and amused, selfies on social media, like, “Look, Ma, I’m in a museum!” Other people told us, “I don’t have any copies of my zine anymore. Can we get a copy from your copy? I’m so glad someone saved this.”

Stephanie Syjuco: These are definitely instances of a radical shift in context and presentation—from being circulated among young people and activist communities to the formal, historicizing museum.

Astria Suparak: There’s a world of archive and library ethics that I was learning about as I went along. Some zinesters originally made their zines for a small set of people that they personally handed their zines to. There’s a question of whether a zine should live on, like online, for a different time and for different people. I think the general route is to try to contact the original maker and ask if they are okay with the new context. Although a lot of zine makers used pen names or just their first names, so it’s really difficult, almost impossible, to track them down, especially with zines from the early 1990s or older, before widespread Internet use.

In a discussion about zine archiving, someone said their reason for not wanting their old zines to be available online was because images tend to get separated from their context on the web. For example, understanding page 12 might require page 11 to be read beforehand, to build to that moment.

Stephanie Syjuco: It’s a good point. The zines you chose are so important because they could influence or inspire the same ethos down the road. But is it antithetical to put something super punk rock, or radical, or political in a museum? I think a common critique is that by becoming institutionalized, objects are neutered of their politics. We may have had the same critiques voiced against us.

Astria Suparak: That assumes that the museum is a neutral space—or a grave.

Facebook post by Ramdasha Bikceem with her zine Gunk in Alien She, at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, 2014. Courtesy of Ramdasha Bikceem.

Zines and fliers in Alien She, curated by Astria Suparak and Ceci Moss, at Pacific Northwest College of Art, Portland, OR, Sept. 3, 2015 – Jan. 9, 2016. Photograph by Astria Suparak.

Stephanie Syjuco: The CITIZENS show featured what appear to be portraits of anti-fascist activists, but they were actually UC Berkeley students who witnessed some of the major political protests that happened on campus in 2017. These students weren’t directly involved, but they were deeply affected by the events and began to consider themselves as political beings. I invited them to act as stand-ins for composite portraits of anonymous activists who cannot be photographed. I wanted to represent these activists in some way, to create humanizing portraits of them.

Astria Suparak: And identifying activists and other targets through online image searches and social media now presents a real danger.

Stephanie Syjuco: Yes, totally. The potential fallout from doxing [the tactic, favored by the alt-right, of exposing an anti-fascist activist’s identity and subjecting them to direct threats of violence] is dangerous and very real. I think it has muzzled people, facilitating even more anonymity. So, when trying to create images of resistant voices, it’s important to protect people. That’s similar to the need for some zine writers to operate under pseudonyms: You’re sticking your voice out for something that could put you in harm’s way, but you’re also trying to make sure you’re connecting with those who you need to. You have to be legible in certain ways and illegible, or unidentifiable, in other ways.

Astria Suparak: We’re in the era of the anonymous online troll, and people still can’t separate hate speech from the right of freedom of speech. There are academics and artists who are die-hard free-speech advocates, but some people are finally seeing how hate speech results in serious abuse and deadly consequences.

Stephanie Syjuco: The term “free speech” is thrown around so easily, and it’s ingrained in all of us that it’s one of the pinnacles of what it means to be an American because it offers us a diversity of opinion. It was a shock to me when I realized that, legally, hate speech is free speech.

Astria Suparak: In America.

Stephanie Syjuco: Yes, good point. I heard from friends, who are citizens of other countries, that hate speech is not intrinsic to the idea of free speech; it’s a legal designation. UC Berkeley has a motto, “Fiat lux” (Latin for “let there be light”), supporting the notion that if you put ideas into the world, there will be an enlightened, dialectic sorting out of good ideas versus bad ideas. I agree with it on principle, but how it’s actually unfolding is a problem that needs fixing, given the power dynamics of how hate speech—attached to white supremacist, anti-LGBTQ, and anti-immigrant xenophobia—directly bullies, belittles, and threatens people.

Astria Suparak: In forums where the phrase “freedom of speech” is bandied about the most, it’s not presented honestly. Speech has always had legal constraints, and the idea that it’s free is a falsehood in America. There are legal restrictions against child pornography, blackmail, and yelling “Fire!” in a theater. Those kinds of speech create public threats or personal harm, as do incitements to violence, and hate speech is punishable in many countries.

Stephanie Syjuco: As artists, we’ve been taught to champion free speech because we associate it with the idea that our work—depicting our lived realities—will be protected. Because of the 1980s government censorship of artists—such as Robert Mapplethorpe, Karen Finley, Andres Serrano, and others who were targets of NEA defunding—many in the art world are familiar with this issue. It depends on what side is taking advantage of free speech, it seems.

For many people, the reality of some of the problems with free speech hasn’t touched them directly, so they’re still invested in it as a philosophical concept.

Astria Suparak: I feel like there have been great strides in the freedom-of-speech debate in the past few years. There have been many brilliant discussions about these issues. But that might be within my bubble, where I’ve chosen to follow thinkers, writers, and artists of color—people who are the targets of most of the hate speech, who are being attacked and murdered because of their perceived race or ethnicity.

Stephanie Syjuco: I’m really curious: As somebody who is a curator and an organizer of culture, for archiving and for display purposes, have you found that the last year and a half has changed your focus, or your opinion on what you do, and how you do it?

Astria Suparak: I’m much more deliberate about how I’m using my role, resources, and platform. I’ve always been particular about which voices and imagery, and which ideas and stories I want to elevate or support, as a curator. I’ve become more attuned to racial politics, colorism, white supremacy, and related issues, particularly with the rise of Black Lives Matter and the recent discussions around Indigenous identities and representation in the art world. Throughout most of my career I’ve worked in predominantly white scenes like experimental film and alternative music—and art! And I’ve been employed by very white institutions in smaller cities.

I moved to the Bay Area a couple years ago, and it’s been really important for me to be around more people of color and people who are actively engaged in thinking about and working on these issues.

Stephanie Syjuco: Last night I was talking to another curator of color based in Portland—which is one of the largest cities in America with the fewest people of color, the result of historically racist, exclusionary policies. We were thinking about questions like: When I make art, who do I generally assume the audience is? Do I assume they are people who look like me, or are they people who don’t look like me who I’m attempting to educate about the reality of people like me? And I’m starting to get tired of that—of all the extra labor that goes into having to make sure that your project or work is actually also a pedagogical tool, so that white audiences can get on the same page to even understand the nuances of what you’re saying.

I’m concerned about how our work—our speech—as artists and curators of color is hampered by the inability of many people to even hear what we’re saying, even when we’re saying it.

Astria Suparak: Yes! That right there.

But we also have these double roles, as educators, as curators, to provide context, through writing, lectures, tours, outreach, and so forth. At least, this is the way I approach curating; I usually want to bring in, and collaborate with, people who aren’t comfortable with art, or within an art space, or with these issues.

Like with my recent series around sports. The prevailing belief is that sports and art—or sports and politics, for that matter—are two completely separate realms. I don’t know if I can get away from plotting how to lure people in and how to contextualize for those who aren’t familiar with all the references, or for those who feel like they are outsiders.

But I understand that pressure, both from the exterior and internalized, to imagine a default white audience. And I understand that exhaustion.

Stephanie Syjuco: That is our supposed target audience—or it’s assumed that it should be. Otherwise you’re not addressing “everybody,” which is ironic.

Astria Suparak: Sometimes I want to enter a space with the assumption that everyone understands that we’re living under white supremacy.

Stephanie Syjuco: Wouldn’t that be amazing?

Astria Suparak: I’ve been trying to do that more often, but I’m not sure if it’s landing right.

Stephanie Syjuco. Cargo Cults (Headbundle), 2016. From the series “Cargo Cults,” this work revisits historical ethnographic studio portraiture via fictional display: using mass-manufactured goods purchased from American shopping malls and restyled to highlight popular fantasies associated with “ethnic” patterning and costume. Archival pigment print; 40 × 30 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Catharine Clark Gallery, San Francisco, and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York. © Stephanie Syjuco.

Stephanie Syjuco: A friend told me she watched two people view my Cargo Cults photographs [at MoMA in the exhibition Being: New Photography 2018] and ask each other, “I wonder where the woman in this picture is from. Her culture looks beautiful and amazing.” The photographs were staged, fictional images that critiqued racist ethnographic photographs from the 1800s. My friend finally went up to them and pointed out the visual cues and text that indicated this wasn’t a real culture. And they were shocked because they couldn’t read the image that way; it was illegible to them, despite being perfectly clear in many ways.

So, even when you’re saying something, you are not being heard. The flip side of this demand for free speech—and more speech—is that you could be saying something, but it doesn’t matter. There’s a distinction between utterance and legibility. In this case, utterance is the desire for someone to express her lived reality, but a large portion of the dominant society is unable to even understand her, even when she is speaking clearly. So she is rendered illegible.

Stephanie Syjuco. Total Transparency Filter (Portrait of N), 2017. Archival pigment print; 30 × 40 inches. Courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York. Portrait of an undocumented individual who received her college education through DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), and whose status in the United States is now under threat; cloaked under protective anonymity, she occupies a tenuous space between invisibility and visibility. © Stephanie Syjuco.

Astria Suparak: I’m also thinking of memeification, and how the goal is to distill the message so that there is no subtlety, so it’s crystal clear, in order to propagate successfully. But then that exact same image can be used for a totally different purpose!

For example, the NFL kneeling ban: Even though the players have been unequivocal that they are protesting police violence against Black people, the white NFL owners, fans, US president, and others have created this totally different narrative that says that the players are disrespecting the military. That’s a dishonest, intentional misconstruction.

Stephanie Syjuco: Yes, exactly. It is ironic that you could be saying something really radical in your moment of “free speech,” and it still doesn’t necessarily go where you want to go because it can get turned 180 degrees or miscontextualized.

Astria Suparak: Or a critique can be derailed because people are focusing on one of the words used, rather than the substance.

But then some people, usually white, get the benefit of the doubt.

Stephanie Syjuco: Here’s another example: Melania Trump’s infamous jacket that said “I REALLY DON’T CARE, DO U?” when she was visiting immigrant children in detention centers. Now I feel like we’re a podcast or something, recalling recent political moments! Okay, it is free speech. Of course she has every right to wear this most tasteless thing wherever the hell she wants. But there will be fallout, a backlash. There are contextual ramifications.

Astria Suparak: Some people thought it was an intentional distraction to what her husband was doing.

Stephanie Syjuco: Was it a dog whistle? One can read it in a totally awful way, which I do. We’ve strayed from talking about art, but I think this does go back to the idea of impact: what one says and what one puts out in the world has impact.

Astria Suparak: I want to loosely connect that jacket to art, through fast fashion often taking inspiration from artists and from the aesthetics of protest. I don’t mind that we are encompassing all of this. And it’s not unconnected to the photos you made in CITIZENS.

Stephanie Syjuco: Yeah, you’re right. Culture gets absorbed that way. The style of writing on that jacket is obviously influenced by punk rock.

Astria Suparak: That jacket is a derivative of military style. And punk detourned army gear. Since we’ve been talking about misinterpretations and omissions: What do you feel is often overlooked, in writings about your work?

Stephanie Syjuco: I’ve been making work for more than two decades. I think that’s long enough to have built up a complicated and varied art practice. Based on my interests, the work manifests in different forms. Sometimes, they are temporal events; sometimes, they are installations of thousands of objects; sometimes, they are online databases. I feel like the work can be hard to pin down, and I am fine with that.

What’s problematic for me is the art world’s tendency to focus on selected forms, which silos artwork into discrete categories (for example, “activist oriented,” “social practice,” “textiles,” “photography,” “artist of color”). While these are not untrue categories, they are also convenient ones that can fit into a curatorial theme, article, or what-have-you. I think there’s something interesting about acknowledging extreme diversity of form in an artist’s work. The work should be as varied and interesting as you are, as a person, and even contradictory of the expectations placed on any of those individual categories.